A Pioneer of Latinx Identity

Remembering Laura Aguilar’s unapologetically queer bodies.

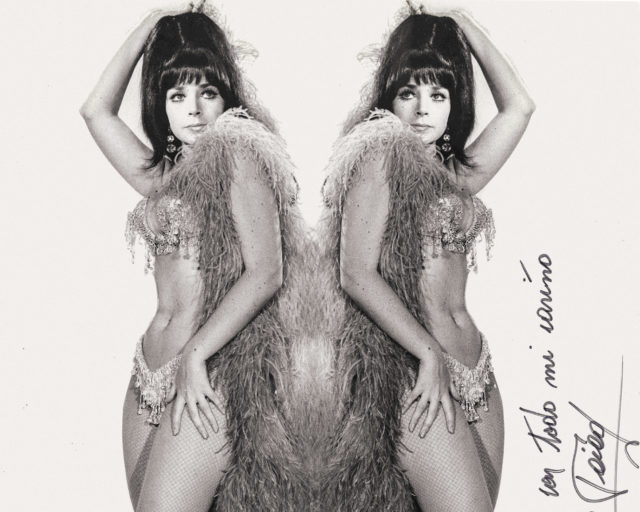

Laura Aguilar, Plush Pony #2, 1992

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Photographer Laura Aguilar was one of the pioneers of Latinx identity. In her fin de siècle pictures, Aguilar depicted “Latina lesbians” in pompadours, families all cuddled together, and nonbinary babes showing off their bodies. In creating this community of images, she left us a foundational text for how we invent and collaborate on brown selfhood today.

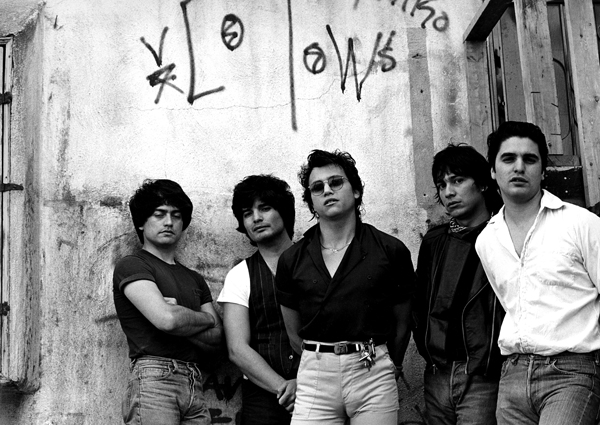

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

The term “Latinx” first appeared on the web around 2004, according to scholar Arlene B. Gamio Cuervo. The term descends from the appellations Latina/o, Xicanx, Chicanx, Latin@, and Latine, which rebelled against the gender-assuming “Latino” and “Latina,” and the grumble-inducing but always popular “Hispanic.” Latinx evokes a pan-gender brownness that possesses blurry edges, queer sensibility, and an intersectionality of affections and oppressions.

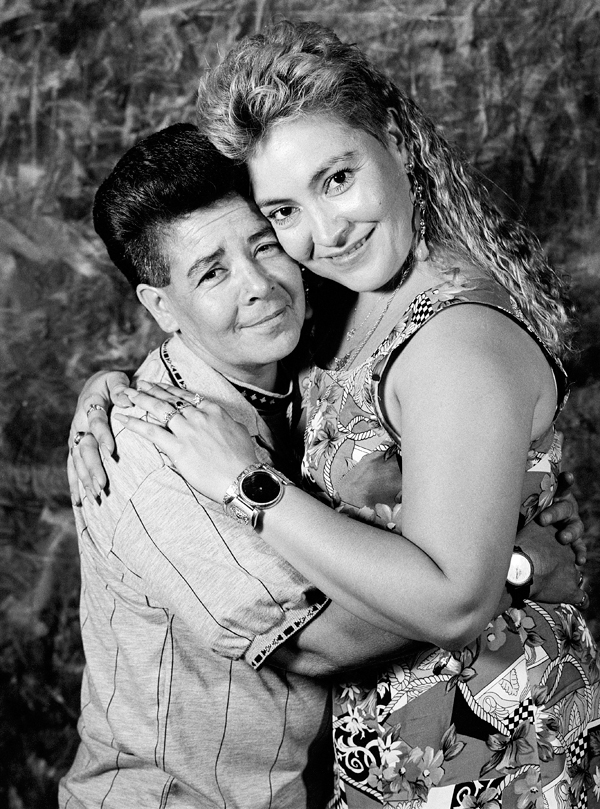

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Today, these values are expressed by artists such as the conceptualist Rafa Esparza, who makes built environments out of tierra alongside his father, who had expressed discomfort with Esparza’s sexuality. They also imbue the photo art of Guadalupe Rosales, whose work engages found snapshots of manifold Latinx party crews, as well as that of trans musician/banshee Elysia Crampton and critical race burlesque performer Xandra Ibarra. Each of these creators burns down the cells in which supposedly discrete Latin American personas have been segregated. In so doing, they live out some of “Latinx”’s promise, which was imagined decades earlier in Aguilar’s coruscating photography.

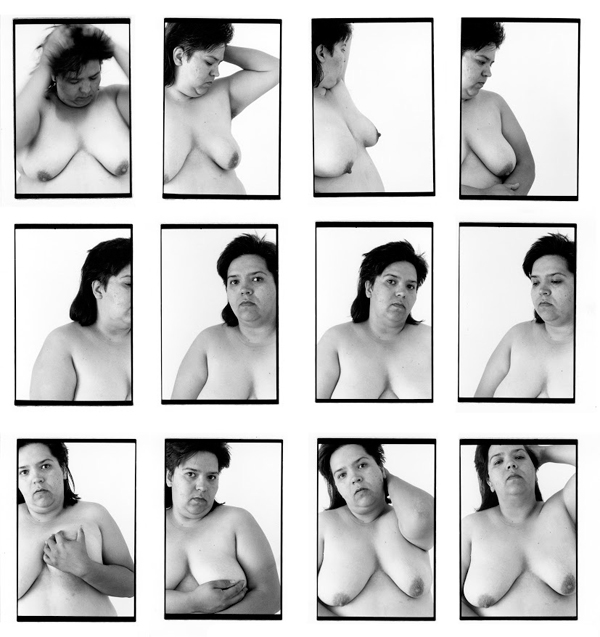

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Born in San Gabriel, California, in 1959 to the Mexican American Paul Aguilar and the half-Irish Juanita Grisham, Aguilar was dyslexic, large-bodied, lesbian, and of a complex racial background. Around 1988, Aguilar produced the famous Latina Lesbians suite, which describes identity as an evolving community invention. In her own self-portrait, she’s shown smiling in her bedroom, wearing shorts and a cowboy hat. Beneath the picture, she’s written: “Im not comfortable with the word Lesbian but as each day go’s by I’m more and more comfortable with the word LAURA.” And in Yolanda, an unsmiling, square-jawed heartbreaker, wearing jeans and a navy Izod polo, poses with her hands in her pockets. Under her image it says, “My latina side infuses my lesbian side with chispa & pasión.”

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Aguilar’s art gained energy and texture as the ’80s crested into the ’90s. In her early ’90s Clothed/Unclothed series, she represented a Latinx woman with a little sign reading “Fuck Your Gender” affixed to her vagina. Aguilar included this model within a panoply of other portraits that are naked, multiracial, queer, and beguilingly interfamily. From 1996 to 1999, Aguilar made some of her most well-known works: Her Nature Self-Portrait and Stillness portfolios reveal Aguilar undressed in the southern California desert, positioned next to rock pools, burned trees, and stone outcroppings. Her body’s lush curves and vibrant attitudes—arms up, dancing; standing with her hands on her hips and staring into the forest—do not hide the frailty of her skin, or the vulnerability of her breasts. To be a brown, gay, full-framed woman in the world takes courage, these images say, and you have to invent a self that the hegemony insists does not, and could not, exist.

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

With their gentleness and beauty, the Nature Self-Portrait and Stillness photos glimpse at Latinx melancholy experienced avant la lettre. These works cap off Aguilar’s decades-long study of the ways in which exclusion and anguish helped forge the brown and contingent self. In one of the installments of 1993’s Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt Her series, Aguilar stands nude before the viewer while mouthing the barrel of a gun: “So don’t tell her Art can’t hurt,” she printed neatly beneath the portrait. “She knows better. The believing can pull at one’s soul. So much that she wants to give up.”

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Aguilar created other narratives of agony, too—the 1990 Three Eagles Flying shows her standing before a black background, with her head wrapped in the Mexican flag, her breasts bared, the U.S. flag tucked around her waistline, and a rope tied around her throat. And Aguilar fearlessly demonstrated how poverty and neoliberalism shaped identity with their own carving knives in 1993’s Will Work for #4, which portrays her standing under the word “Gallery” (perhaps she was at Santa Monica’s Bergamot Station) and holding up a sign that says Artist Will Work for Axcess.

© and courtesy the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

In the way back of the ’80s and ’90s, Aguilar taught us that living as Latinx meant looking hard at what’s within, while also reaching out to the larger world. Like the writings of Audre Lorde,Cherríe Moraga, and Gloria Anzaldúa, her work presaged the vision of contemporary artists who embrace unbounded community, not to mention the intersectional activism of Black Lives Matter and #NoBanNoWall. Aguilar died tragically at the age of fifty-eight in a hospice in Long Beach, California, on April 25, 2018, and deserves to be remembered as a foremother of the modern Latinx state. Without her photographs, this morphing and creative identity would not exist in its current form.