Lingua Photographica

This essay is one of a series of online-only texts commissioned to accompany Aperture‘s Spring 2013 issue, “Hello, Photography,” which examines the state of the medium in a time of great change.

Of all the changes the web has undergone since its inception in the early 1990s, the most jarring, of course, is the way in which its related technologies have become enmeshed in almost every avenue of daily life. The Internet (at least in the places on the globe where it’s freely available) is no longer a novelty or pastime; it’s a fundamental aspect of contemporary experience. Millions of users fluidly shuttle between online and off, often functioning in both realms at the same moment.

In this dual reality, photography has taken on an intriguing role. In a virtualized world of constant information intake, the ability to read photographs instantly, to say nothing of the unprecedented ease of taking pictures and disseminating them online, makes photographic imagery the new lingua franca.

But while photography is more pervasive than ever, it is also every day less consciously photographic. Photographs are now pics: the mutable, disposable flotsam of daily life. Beyond even the automated comforts of the point-and-click or the one-time-use disposable camera, a modest telephone can now snap and distribute a quick digital image with ridiculous ease—an image with a richness and clarity that would have been enviable to previous generations of photographers. For artists, these new conditions, and the changing valuation of photographs, present myriad creative opportunities.

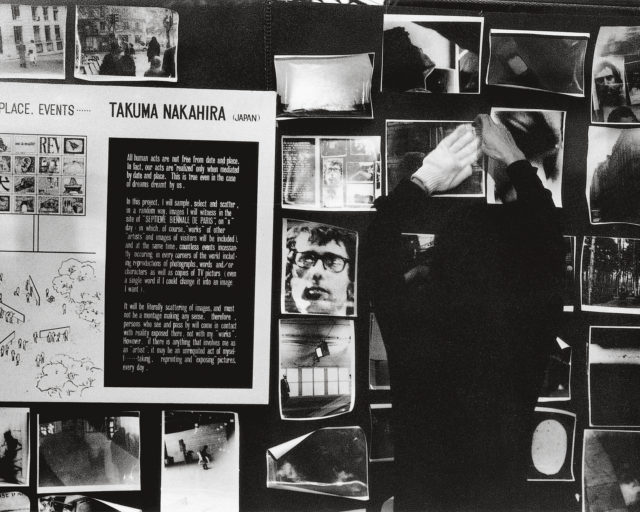

This is by no means a new area of investigation. Throughout the history of photography, artists—from John Heartfield to Robert Heinecken to Cindy Sherman—have explored the shifting status of the photographic image: that is, the way photographs are distributed, used, and received. Many artists working in and around the Internet today continue this inquiry, opening up new ways of understanding how photographic imagery functions in contemporary culture, with the new technologies that have now taken hold of our lives.

Katja Novitskova, Earth Calls 2 (Night), 2012

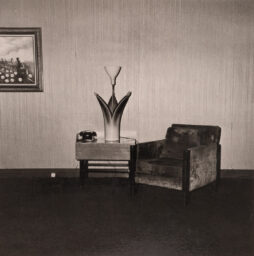

Jeff Baij’s CL Still Life series (2010) explores the aesthetics of banal images uploaded to the classified-ads website Craigslist. His particular focus here is on inexpensive dishes, glassware, and other dull items of home décor. His eye is drawn to low-resolution images, most likely taken with cellphones, almost certainly uploaded without artistic intent. Every once in a while an image will (accidentally) have an interesting composition, or will strike Baij as so supremely boring that it transcends its ostensible function. When he finds such images, he imports them into Photoshop and slaps on a raw filter, making the subjects at once humorously self-important—but also glowing, haunted, memorably strange.

The pursuit of the banal is an amply rewarding endeavor. In their blog Tanner America, artists Aaron Graham and Shawn C. Smith pose as suburban parents Allison and Rob Tanner, who use default web 2.0 blogging tools to “share photos with family and friends.” Photographs found online are collaged together and combined with short captions, satirizing the way many Baby Boomers and other non-digital-natives often awkwardly use the Internet. The result could be a cheap stunt, but the artists are able to strike a David Lynch–like balance of funny, creepy, bland, and surreal. Like Baij, Graham and Smith are mining a particular type of photography familiar to anyone who surfs the Internet on a regular basis—but then playing with the images, making them alien to themselves.

Katja Novitskova’s Earth Calls (2012) presents two images, each featuring an empty landscape (found on Google Earth) combined with an image of a man holding a smartphone (photographs culled from the blog platform Tumblr). In Earth Calls I, a man is seen taking a nude self-portrait by holding the phone up to a mirror. In Earth Calls II, another man, in a baseball cap, looks down in order to manipulate his phone. By themeselves, these images, like the empty Google Earth landscapes, are no more than random Internet finds. Through Novitskova’s simple juxtapositioning, though, the generic landscapes become abstracted planes and the men’s poses are elevated to something almost classical: overall, the work has an air of the elusive and mysterious.

In each of these bodies of work, there is an element of in-between-ness: the photographs seem caught between two polar attractions. There is of course an essential, definitive, inescapable irony in the use of these particular images. But there is another side to them, too: a gentle humor, perhaps a genuine affection for the subjects. And although in some ways the images in these projects are richly colorful and well-composed, there is a decided anti-aesthetic to them as well: they revel in the sort of low-res trashiness that characterizes so much photography on the web.

This disorienting in-between-ness can take other forms as well. Bunny Rogers’s ongoing project 9 Years is made up of screen captures taken from the artist’s experiences in the virtual landscapes of Second Life. Rogers places her avatar, Bunny Winterwolf, in sexually provocative situations with other users’ avatars. She then snaps hundreds of screencaps, trying to get one that strikes the correct intuitive balance. The images she ends up with are lush and evocative, but also odd and dark—sexuality becomes something both erotic and detached, both giddy and nightmarish.

Ryan Whittier Hale, Abomination, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

With similar affect, in Ryan Whittier Hale’s Null Presence series (2012) android bodies exist in an uncanny space between emotional empathy and antiseptic nothingness. Borrowing compositional strategies from Mannerist paintings and imagery inspired by science fiction, Whittier Hale’s worlds seem on the verge of generating emotion—both between the figures and between the work and the viewer—but that feeling is swallowed into a void of artificiality and surface flatness. Whittier Hale says that with this project, he is “working with the idea of something that simultaneously has a presence and is completely vacant.”

Such dichotomies correspond, I believe, to a larger sensibility evolving on the Internet: the liminal feeling of life in the digital age—perched as it is between the virtual world and the physical, the organic and inorganic, the emotional and the disaffected. Without offering value judgments, these series open up those threshold sensibilities and allow viewers a peek inside.