When the Party Came to Lagos

In 1977, when the photographer Marilyn Nance traveled to Nigeria for FESTAC, she discovered a euphoric reunion of the African Diaspora.

Marilyn Nance, Mid-festival, the first contingent of FESTAC ’77 U.S. participants greets the second U.S. contingent at the Lagos airport, 1977

Marilyn Nance can’t find Stokely Carmichael. She is compiling a bibliography for her forthcoming book, Last Day in Lagos, which documents her time as a photographer at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, or FESTAC ’77, as it is popularly known. Nance has a lingering, unshakeable, urge to include a book by Carmichael. His life’s work “sprung from being a young intellect to a civil rights worker to a Pan-Africanist,” she told me recently. “My life, while much more humble, follows a similar trajectory.” The Pan-African revolutionary, later known as Kwame Ture, attended the 1969 Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers, Algeria, where Eldridge Cleaver’s Black Panther Party also held court. Combing through photographic archives, books, and his own writings, Nance believes that the radical lover of Black music and culture should have been at FESTAC ’77. But it has never been easy to tell who was actually there, especially among revolutionaries always on the move.

Nance’s and Ture’s paths had crossed a couple of times before. The first time, in the late 1960s, Nance was a member of the Black Cultural Society at the Bronx High School of Science and the group invited Ture, an alumnus, to speak. The second time, about a decade later, was in West Virginia at the John Henry Memorial Blues and Gospel Jubilee. Then, there was an All-African People’s Revolutionary Party event at Syracuse University, in the late 1980s. “If our paths crossed three times, then, why not at FESTAC?” she asks.

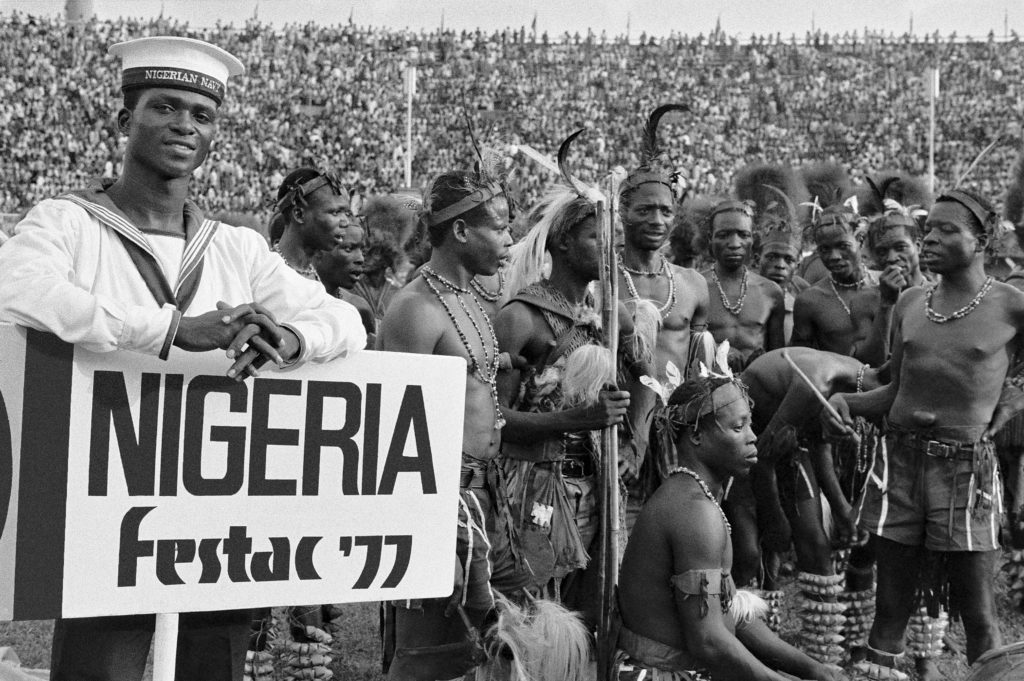

Over fifteen thousand artists, dancers, actors, musicians, scholars, activists, photographers, filmmakers, and other cultural workers from the extended Black family came together for a month in 1977 for FESTAC. Officially, it sought to “provide a forum for the focusing of attention on the enormous richness and diversity of African contributions to world culture.” What makes one look back at FESTAC ’77 with wonder is the sense that it was an extraordinary representation of arrival—a high point of exchanges, conversations, and overtures Black people had been making with and toward each other in response to the historic rupture of slavery. As early as 1859, Black abolitionists such as Martin Delany were scoping out possible sites on the African continent for free Blacks to return to. In 1900, W. E. B. Du Bois closed the first Pan-African Conference, held in London, by declaring “the color line” as the problem of the twentieth century. At the 1956 Conference of Negro-African Writers and Artists in Paris, Richard Wright declared that African Americans were in “the technological vanguard” among Black people and “would prove of inestimable value to the developing African sovereignties.” These initiatives pulled together the creative and political energies of Black people all over the world to harmonize efforts in a collective liberation. Ten years later, Duke Ellington, Langston Hughes, and Alvin Ailey joined Wole Soyinka and Nelson Mandela at the 1966 First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal.

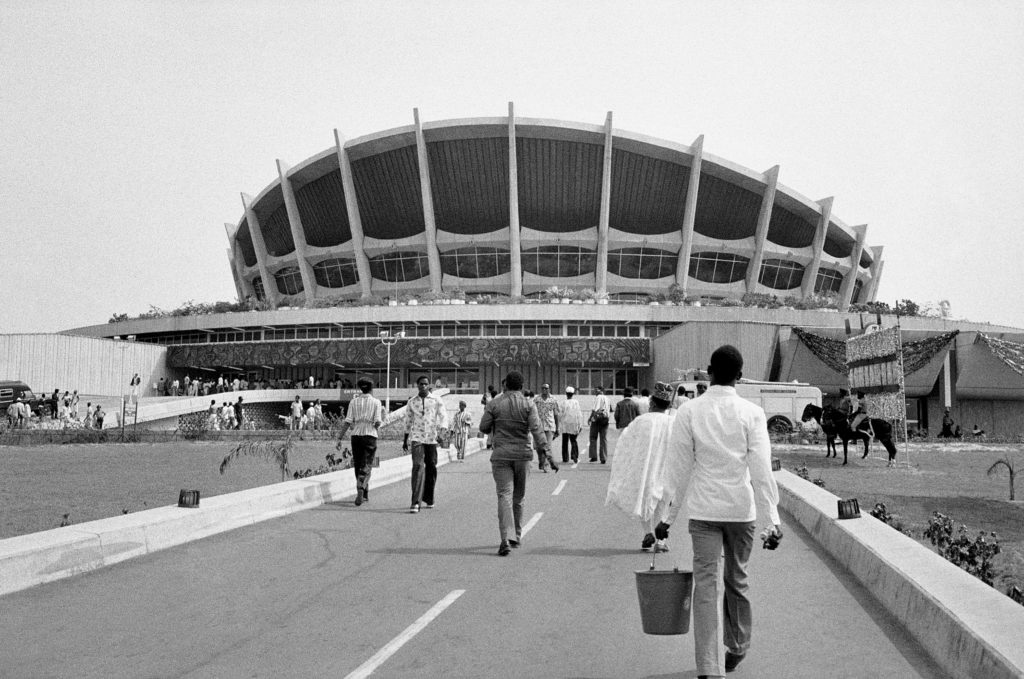

FESTAC ’77 was bigger. Nance, who attended and photographed this historic event, describes it as the Olympics, a biennial, and Woodstock combined. Ebony magazine declared that “for the first time in 500 years, the black family was together again.” This was possibly the largest group of African American artists, over four hundred of them, to have traveled to the African continent together. Those on this “symbolic reversal of the transatlantic slave trade,” as Nance has described the 1977 moment, included Stevie Wonder, Jayne Cortez, Betye Saar, Faith Ringgold, Paule Marshall, and Jeff Donaldson.

A photographer for the U.S. contingent, Nance made images of the great diversity of people at FESTAC. Getting there hadn’t been easy. In 1974, she submitted her portfolio to the festival organizers to participate as an artist, sending, among other things, a photograph of her grandmother sitting at a lunch table in Alabama. In 1975, Nance heard back that her work was accepted. But the next year, she was informed that the number of attendants from the United States—herself included—had been cut. Discovering that there was a need for a photo-technician, she made a case to be chosen, especially since the photograph of her grandmother had been lost by the organizers. Nance called the offices of the festival’s North American headquarters, housed in Howard University’s art department, every day until they relented. There was no pay, or camera, or film. Just a ticket on Capitol International Airlines to Lagos and back.

With a similar spirit of persistence, Nance stayed for the full length of the festival rather than the two weeks she was allotted by the organizers, allowing her to see and document it in a comprehensive way. The resulting photographic archive remains one of the largest visual records of this monumental occasion, where the poet Audre Lorde “felt the earth move.” A selection from Nance’s approximately 1,500 FESTAC images will be collected in Last Day in Lagos.

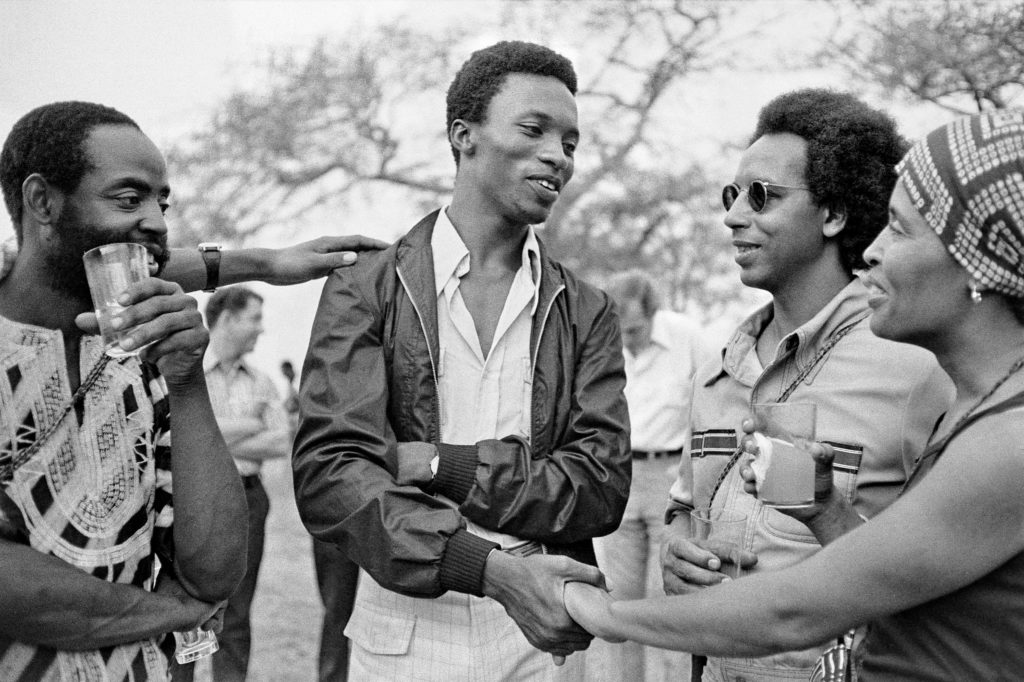

At FESTAC, Nance was less interested in the contentious academic arguments around a definition of Blackness that had carried over from previous international gatherings. (The words Black and African in the festival’s name were used to allow for the inclusion of North Africans who might not consider themselves Black.) Instead, Nance was busy in the streets and arenas, at cafeterias and parties, interacting with people and collecting on-the-scene photographic representations of the joy of recognition among participants from around the globe, of spontaneous relations being formed through identified commonalities, and of the forging of communities and collaborations. This trip was Nance’s first time traveling outside of the United States, and, as the spirits of the ancestors would have it, all of Africa had come to meet her.

Seeing the faces of friendly folks from the other side of the world, Nance thought she recognized characteristics of her U.S. relatives and acquaintances—in the cadence of speech, in the pitch of laughter, in facial expressions. She had a desire to visually investigate Africanisms—the shared habits, tendencies, and proclivities observed wherever Blacks had been sprinkled. Nance had long thought of herself, although born in the United States, as African. Here, in Africa, she was seen as an American. She began to grapple with her place, and that of African Americans in general, in the larger Black diasporic family. “I got an understanding of the history of how we became African Americans,” she says. “I knew it. But at FESTAC, you could feel it.” Feeling complemented a political awareness of Blackness drawn equally from her African ancestry as from her political education and knowledge of history informed by the civil rights and the Black Arts movements. “I feel connected to other people,” she says, “and my photographs document that connection.”

Nance was born in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, in 1953. Her father and mother had left Wadesboro, North Carolina, and Birmingham, Alabama, respectively, as part of the Great Migration north. Her grandmother (who thought of herself as African and was most excited about Nance’s “return” to Africa) was born in 1886. “Her father would have been born in the time of enslavement,” Nance states, “meaning our family is only two generations removed from having been enslaved and one generation removed from sharecropping.” As a child, Nance came to know family members primarily through photographs. Her mother would point out people and tell her their stories. At age eight, she received her first camera, a gift from her cousin that is still in her possession. Nance would graduate from New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, study graphic design at Pratt Institute, train in audio and film production at the Institute for New Cinema Artists, and earn a master of fine arts degree in photography from the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Nance’s archive remains one of the largest visual records of this monumental occasion, where the poet Audre Lorde “felt the earth move.”

Arriving at FESTAC, at age twenty-three, with a wide multimedia skill set was beneficial. But a more important foundation for her work, then and later, is the political education on which Nance’s craft is erected. Her mother’s father was a labor organizer and only in adulthood did she realize that never crossing a picket line isn’t a commandment everyone’s parents held them to. From middle-school days, she remembers conversations with her sister about demonstrations demanding summer jobs for Black teens. In 1968, the year Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, she attended her first Black Power rally while in high school. Her formative years were suffused with the political energies of the civil rights movement and the creative energies of the Black Arts movement, which encouraged art with the purpose of awakening consciousness, forming community, and striving for liberation. “I really believed in all African people,” she says, “because that had been my training, my political education.” Nance immersed herself in the recordings of the musician and activist Rahsaan Roland Kirk and the teachings of Malcolm X, participated in Black cultural rallies, and went to see plays by Amiri Baraka and Ed Bullins, who served as the minister of culture for the Black Panther Party. “FESTAC was a triumph of the Black Arts movement,” Nance explains, “because in the Black Arts movement, there was always a reference to Africa.”

In Lagos, and in true Pan-African style, Nance roamed from one contingent to the next. Language could be a big barrier. Nance recalls a lot of smiling, staring, and dancing as ways of communicating. At the lunch table, you might find Indigenous Australians across from you, musicians from Burundi to your left, and North African intellectuals to your right. “‘Who are you?’ and ‘Oh, look at you!’ were the ethos,” she says; physical presence was the currency of exchange. Tagging along with Nance through her photographic archive is a wild ride. We see not just Lagos but journey also to Ile-Ife and Benin City. We feel the blistering afternoon sun; squeeze into a rehearsal of Sun Ra and his Arkestra; and dance with Stevie Wonder and Miriam Makeba at Fela Kuti’s nightclub the Shrine.

With either her Canonet point-and-shoot or Miranda Sensomat cameras ever present, Nance navigated this month of encounters by quite literally being in people’s faces. This immediate nearness and proximity, almost making her invisible to her subjects, gives the viewer a strong illusion of being present on the scene. In one image from the opening day ceremony, the frame includes no action from the festival but is zoned in on the crowd. Standing on the ground level is an eclectic collection of observers—women wrapped in their traditional cloths, beads draped gently around their necks; a fedora-wearing man with a tailored shirt and trousers; a young photographer with a pinkie ring, firmly holding his folding camera; above, on a staircase and landing, facing the photographer, are naval men in white shirts and sailor caps, assorted security men in their starched uniforms, and a group of general onlookers. The photograph is filled with people, yet there is a sense that you are interacting with each person on their own terms, sharing their perspective—wondering what has caught their attention as the rich and active atmosphere of the festival has drawn everyone’s gaze toward a different direction.

“While her images of FESTAC ’77 have left an indelible mark on how we understand the festival visually,” Oluremi C. Onabanjo, an associate curator in the department of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, says, “I feel FESTAC ’77 also left its own mark on her, as a formative experience in her life as a photographer and adult.” Onabanjo, who is the editor of Nance’s photobook on FESTAC, traces a special attention and interest in bodily expression in Nance’s later work—of the intimate, the sensual, the quiet—back to FESTAC. As Nance states, “It is what is in your heart and in your mind that makes the images.”

An “undying love for the people,” a phrase Nance borrowed from Kwame Ture, is the spirit that inspires her photographs. Attending FESTAC intensified Nance’s commitments to the principles and values of the Black Arts movement. In her coverage of anti-apartheid activism in New York and the vulnerable, ecstatic scenes at the Oyotunji African village in South Carolina, there remains that interest in interchanges of ideas, people, and events found at FESTAC. As Onabanjo explains, Nance’s photography after 1977 “witnesses an amplified scope of vision as to the various transnational spiritual, cultural, and political experiences . . . while showing a finely attuned sensitivity of the place of African Americans within this global context.” She points to Nance’s 1980 images of the Black Indians in New Orleans; her work as a producer on the 1985 film Voices of the Gods, directed by her husband, Al Santana; her image Three Placards from 1986, with the faces of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Elijah Muhammad on placards at an anti-apartheid rally in Central Park; and the place of Yoruba culture in her installation Egungun Work (1994).

Nance is a self-described “digital elder” who seems to bring her archival practice to all her interactions. Perhaps this approach reflects back to her childhood of “meeting” family through photo- albums. In a wider sense, her focus on connecting people and histories corresponds to the African practices of festivals, where it is believed that all generations—the living and the dead—come together. Last Day in Lagos, then, is a festival of its own, a feast for the creative imagination that introduces today’s generation to their artistic ancestors.

All photographs © the artist and courtesy Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

For Nance, the images are “visual medicine,” a reminder of mutual joy preserved for the future. The making of Last Day in Lagos led Nance to rediscover other FESTAC goers. In the process of creating the book, Nance found mementos—address books, cloths, notes, letters—that fueled her desire to bring together what she refers to as the FESTAC ’77 fellowship. Despite the event’s historic nature, on returning, participants found little interest in telling others about their time in Lagos. In March 1977, Kay Brown, of the Black women artists collective Where We At, organized an open house in Brooklyn for participants to share photographs and stories. The following month, the Studio Museum in Harlem hosted a reception honoring U.S. participants. But there was no organization or space created to hold FESTAC archival materials or oral histories. Until relatively recently, interest in the work and experiences of the Black artists who were there has been relegated to a handful of academic articles and discussions. Memories of the festival, outside of the participants and their personal archives, persist in some memoirs and biographies. In 2017, the curator Dominique Malaquais organized the panel “FESTAC ’77 and Other Pan-African Festivals” where participants, including Nance, spoke. Nance’s images are also found in the 2019 book Festac ’77: 2nd World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. In 2021, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, acquired twenty of Nance’s photographs. When I ask Nance why the sudden uptick in interest in FESTAC, she throws the question back to me. “I was ready in 1977 but there was no interest, so we had to go on living,” Nance says. “My job was to make the images. I did the work. I kept the work. I respected the work. I just had to live long enough and wait until the right time came around.”

These days, Nance is occupied with “deep sleuthing” online. She’s tracked down, connected with, and even spoken to some of the people she’s identified in the photographs. Whether or not she finds Kwame Ture in her archive, she is determined that the legacy of the Black Arts movement is not lost to history. U.S. participants at FESTAC spanned generations, from members of the Harlem Renaissance to their creative descendants. For Nance, this is American history, Black history, world history, and art history that she won’t allow to be forgotten. “I’m interested in making sure that someone knew that I was here,” she says. “To be a Black person in America is to always be disregarded, to never be thought of as an intellectual, or an artist, or a collector.” If FESTAC, in the shadow of a civil war, military coups, and political instability, and lacking the technology and degree of connectedness we have in the world today, could be planned and executed successfully in the 1970s, imagine—Nance’s archive seems to tell us what the future could hold.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the title “When the Party Came to Lagos.”