A History of Violence

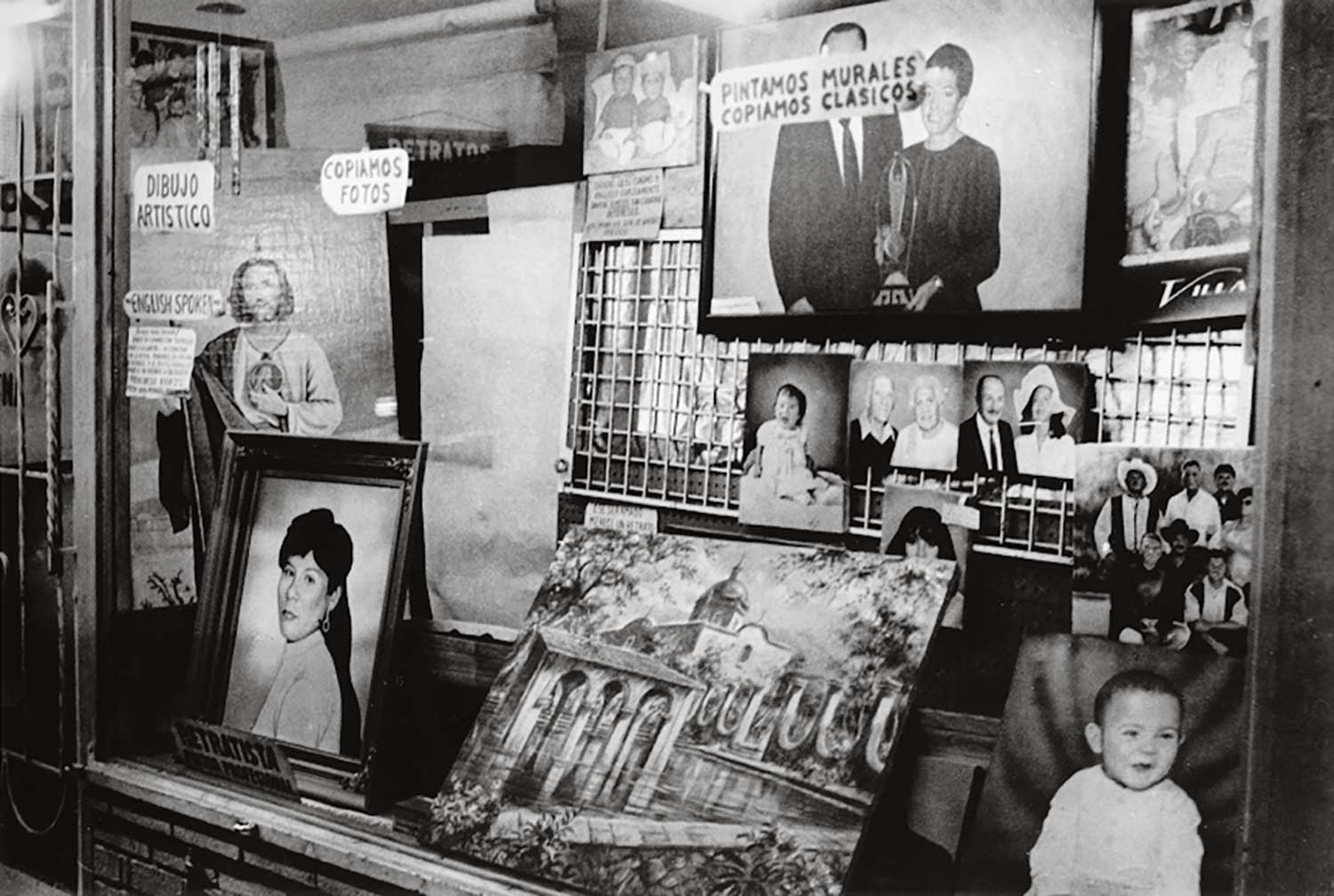

Maya Goded and Mayra Martell are two Mexico City–based photographers who chronicle the stories of families whose daughters have been murdered or disappeared in Ciudad Juárez. Martell has worked her whole life—first in Juárez, her hometown, and then across Latin America—on the identities and vestiges of young women who are absent, yet present in the places they used to inhabit. She has also documented those affected by other forms of violence, such as the mothers of people murdered by the Colombian Army or the everyday nature of drug culture in Sinaloa.

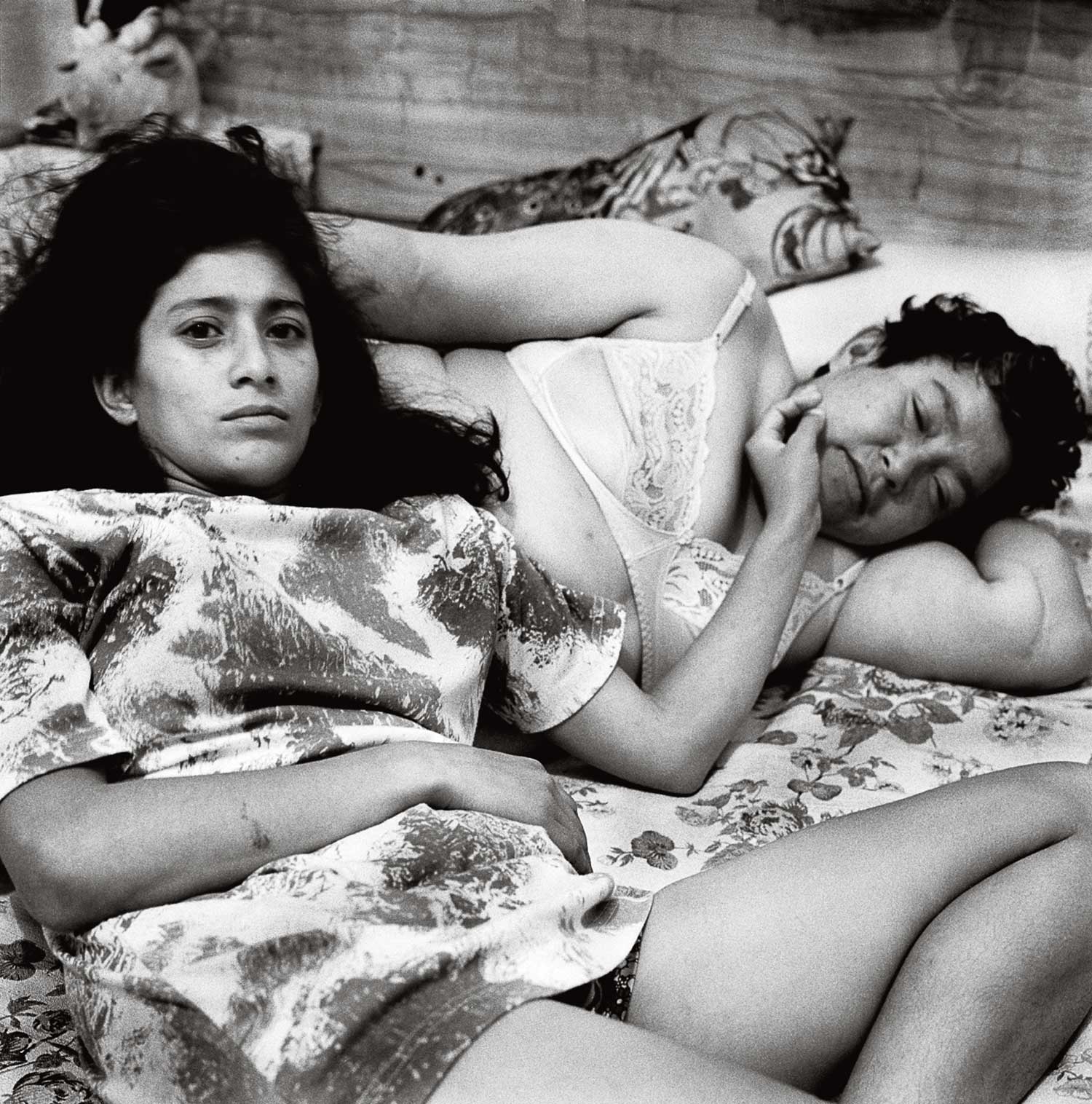

In turn, Goded’s work has been, as she describes it herself, “exploring the subjects of female sexuality, prostitution, and gender violence in a society in which the role of women is narrowly defined and femininity is shrouded in myths of chastity, fragility, and motherhood.” Goded has done so by photographing sex workers in Mexico City and on the U.S.-Mexico border, Afro Mexican communities, and traditional Indigenous healers defending their territory.

In this conversation, Goded and Martell speak with Mexican journalist Marcela Turati about their work portraying the violence suffered by women, how they deal with the pain they photograph, their hesitations and lessons learned, and the conflicts surrounding their lives in Mexico, a country where people continue to disappear—more than forty thousand in the past twelve years.

Courtesy the artist

Marcela Turati: Maya, how did you discover and decide to explore violence against women? And Mayra, how did you decide to go deeper and explore the same issue in your hometown, having grown up in Ciudad Juárez?

Mayra Martell: I am the daughter of a single mother of two, who juggled two jobs. It was very hard to see how the rest of the family and our environment treated her. I noticed violence right then. In Ciudad Juárez, I learned how to treat people very lovingly because you never know what others might be going through.

Maya Goded: When you are out there taking photographs, you are also carrying around your own story. That defines what you are going to look at and what your eyes will prioritize. I grew up with women who also broke through that structure: a grandmother who had to flee her own country, at the age of nineteen, during the Spanish Civil War, never to see her parents again. She reinvented herself and fought on her own.

My mother also left home at the age of nineteen, running away from domestic violence. From the United States, she migrated to Mexico, to study anthropology. Both of them decided to act against the violence they were going through. They moved on. They sought healing. Every time I am out there photographing women, I think of them.

Within excluded communities, women suffered from further exclusion. I started to photograph this normalization of violence. I was interested in women who fought to break patterns and reject whatever society expected from them.

Courtesy the artist

Turati: Maya, in a previous interview you mentioned that you were scared of being a mother yourself. What were you scared of? And what were you looking for when you went to Mexico City’s La Merced neighborhood?

Goded: I refused to be part of this classification of being a good or a bad woman, that Christian moral judgment implying women must sacrifice themselves for the sake of children and their household, not being allowed to live with unrestrained sexuality. With motherhood, I was terrified of losing the freedom that I had fought for all my life. I carried those narratives of guilt. I gravitated toward La Merced. When I arrived in Plaza Loreto, that square seemed like a microcosm. It condensed the different types of violence experienced by women and the solidarity established among them. I saw how men divide women and how violence unites them.

Courtesy the artist

Turati: Mayra, how did you make it into the homes of disappeared women? How did you present yourself, and how did you start portraying their absence?

Martell: One day, I dialed one of the numbers written on the missing-women posters that covered the city center. I knew that that poster had been put up by the missing girl’s mother. The first call led me to Hortensia, the mother of Erika Carrillo. I told her I was a photographer, and that I wanted to interview her. It was obvious that I had no idea of what I would do, and she immediately noticed my clumsiness. She reacted lovingly, invited me to her home, and that’s where it all began. I guess she felt nostalgic when looking at me. I was as old as her daughter back then, and she would ask about what I had done in the past years, where I had been, what I had studied. It was a very weird relationship. Two strangers establishing a close bond where the only meeting point was a person who was not there. I tried to solve the problem of her absence with her presence. I photographed everything that proved that girl’s existence: her room, her letters, her clothes, her photographs.

Turati: Mayra, did the fact of experiencing the intimacy of the victims, those rooms that seem to be memorials, make you feel any sort of commitment?

Martell: It was a situation full of sensations. In some rooms, I could still perceive the smell of the person. At times, I even felt observed by them. I have always known that everything is energy, and that, one way or another, in death or in life, we all share this space. On other occasions, I did not feel anything, as if her spiritual energy was also gone. Of all the cases I have documented, no one has ever returned home.

The only thing I know how to do is to record the situation family members are going through as a way to embrace them and accompany them through the hardships they are living, from which they will never recover.

Turati: Maya, you went from La Merced to Juárez in order to accompany other women, mothers of victims of femicide. Why did you think it was important to bring a camera with you?

Goded: One day, a young, Indigenous, unknown girl was killed at the busiest hotel around La Merced in broad daylight, strangled with her own pantyhose. I followed the case during that whole day. The girl was going to the mass grave. A man said he knew her. Afterward, rumors spread that he was her pimp. I was shocked to see how many girls have their papers, their identities, their names, their birth certificates changed. As we learned about the disappearance of women in Ciudad Juárez, I was sent there to do a report for a magazine.

Ciudad Juárez was the place where I had fallen in love with my husband. Back then, I had traveled with him to that border town in order to attend a film festival, and we did not stop dancing for three or four days. It was a place full of life. But this time, everything had changed. I discovered women were being kidnapped, victims of human trafficking. Then I began to investigate who those girls were: young, poor, most of them without children. The government said they deserved it because they ran around wearing miniskirts and went out at night, and condemned them for breaking the rules. It was very frustrating to talk about women who are no longer there, about the violence that you do not see but that manifests itself in many other ways.

I am not quite sure whether I like this series. It was a hard one. I’ve always fallen short when addressing Juárez. Even though I’ve returned, I always feel powerless. I went back several times in order to work on it by means of different formats—photography, video installations of the children and sisters of disappeared women, and a video of one of the sisters of a disappeared girl, which was subsequently used as part of an experiential theater production.

Courtesy the artist

Turati: Mayra, how did your portrayal of the absences in Juárez mutate into your subsequent work on the types of violence suffered by women? For instance, the case of women in Sinaloa, violence experienced by ficheras [ballroom escorts who are paid to dance, often to live music, with their partners] in Mexico City, or by the mothers of individuals murdered by the Colombian Army?

Martell: Every project is new to me. I put aside every prejudice, start from scratch, and decide what to do in the course of the project. Ciudad Juárez was a real emotional challenge. I came in contact with situations I was not used to dealing with: funerals, interviews with alleged murderers, the monitoring of the nota roja [local newspapers that exclusively publish cases of murder, rape, and other violent crimes]. I would attend trials, accompany mothers to identify bodies that might belong to their daughters. Very painful situations in which I often had to hold back my tears. Now I know that if I had not gone through all those experiences, I would have never emotionally stood the projects that came afterward.

Turati: Maya, when you introduce yourself to a sex worker from La Merced or to a mother who has lost a daughter or a migrant whose newborn son has been taken away, how do you explain that you want to photograph them? What do you do to be accepted?

Goded: You have to be as honest as possible with your intentions, otherwise you will generate false expectations or come across as something you are not. It is hard. You keep on questioning what is ethical. When I started taking photographs, it was very frustrating to realize that you are not going to change anything, that you are a witness, and how uncomfortable it is to be nothing but a witness. Then, over time, you can become involved in activism as a consequence.

Turati: Could you say more about this inner struggle between being a photographer-witness against the impulse to do something in the face of difficult realities. Is this something you have solved, or something you are still trying to solve?

Goded: The inner struggle of being a photographer-witness has changed what I am. In pursuit of topics for my projects, I intend to explore and record all those stories of resilience and self-reconstruction, which often originate in the personal and collective realms, away from the political sphere. My current quest relates to healing, not only on the legal level—which is very important—but also spiritually and bodily, in our connection to the earth, the water. After having captured such hard realities, I want to dedicate my work and energy to documenting small drivers of change, such as the alleviation of pain, which have become a tool of resistance. This fight energizes me.

Turati: What are your ethical conflicts as a photographer, Mayra?

Martell: I have been in conflict with a number of things. The first was having to interview alleged murderers. I struggled not to judge and to carry out the interviews as objectively and humanely as possible.

Turati: How did you manage to stay calm?

Martell: I think what caused me the greatest distress was when I had to leave Ciudad Juárez, because I lived surrounded by mothers who protected me and listened to me, and suddenly I had to turn my life around in a matter of days. From that moment on, I haven’t stopped feeling lonely. It was like a big wave that swept away my whole life and took everything I had. I work through it by doing my job, which is the only way I have to feel present.

Turati: What happened to you? Is this something you can talk about?

Martell: I left Ciudad Juárez at the end of 2009 because I was kidnapped. In those situations, the government appoints security guards to protect you for four days so that you can pack your stuff and leave.

In the end, I left after two days because they tried to kidnap me again, and the people who were in charge of protecting me had to take me directly to the airport. My partner at that time met me there, brought along a piece of luggage, and the rest of my things were shipped afterward.

Turati: That is horrifying. Was it because of your work?

Martell: Things got pretty heavy when [President Felipe] Calderón declared a war on drugs. The city became a mess, so it also became easier to disappear people.

Courtesy the artist

Turati: What types of violence have you suffered as women photographers? Do you have to take care of yourselves in a different way than a man would in a certain kind of place? Are you more vulnerable in this country where it is dangerous to be a woman?

Martell: I am not aware of having suffered violence in my projects for being a woman. As I grew up in Ciudad Juárez, where being a woman, a girl, a boy, a teenager is dangerous, I learned to move around and act discretely when I am being stared at. I am some sort of spy who knows how to respond to each situation: I change my way of dressing, of speaking, and that has always kept me safe wherever I work. I am very much aware of what it could mean to be a woman in these kinds of environments.

Goded: I imagine that all women photographers have gone through situations of violence and normalized them as if they were part of being a woman photographer and traveling alone. This is why I love #MeToo and that the new generation’s questioning it all. The way I take care of myself is by being close to other women. They warn me about any problems or threats. I increasingly look for that solidarity that has protected me so that I can do my work. This is a country riddled with violence and, based on the topics you address, you might become a threat to the state—even without realizing. It is dangerous to both women and men, but danger is always gender differentiated and particularly latent for women in this country. There is always fear in the air.

Turati: What do you do with violence that permeates your skin, that stays in your body when you see it so close and live around these realities for so long?

Martell: I have never actually recovered from all this because, at the end of the day, things keep on happening. Therefore, I believe I will never stop working on denouncing. I have seen horrible things. People who were close to me have been murdered; mothers of disappeared or murdered women are dying; I’ve lost my own personal life so many times that I can’t even remember who I used to be. I don’t quite know where my life ends or starts since I had to flee Ciudad Juárez. I haven’t been able to become emotionally grounded because whatever is happening in that city is beyond my understanding. However, what helps me when I am feeling really bad is to think that, while I might be feeling sad, the mothers of those women and girls must be feeling a thousand times worse, and that pushes me to get up and get down to work. It is necessary to accompany those who are suffering such situations.

Goded: When I was working with cases of disappeared women and then went to Chiapas to do a report, I was very scared by some things that happened to me while photographing. Sadness and horror invaded my body. I couldn’t sleep. One day, when my daughter was thirteen, I did not want to let her go out because I was scared; and she, wise as she’s always been, said, “Mom, those are your ghosts, not mine. Work them through.” I realized I was not allowing myself to say: I am scared, I am feeling sadness, I am disappointed. I stopped taking photographs. I was not traveling on my own as I used to. I did not see the point of photography anymore. I got into psychoanalysis and explored other ways of healing and understanding pain, focusing on the kinds of pain that remain in the body.

I started photographing women who do witchcraft, in the north of Mexico, as well as doing research on Spanish and Indigenous women from the 1700s who healed with plants, were accused of witchcraft, and burned at the stake. I started to heal that pain by learning about them. My current quest began there.

I also went deeper into sacred plants, around which this country has a great tradition, and started working with healers to understand that, even though justice heals, you also have to heal at the energy level, honoring both your ancestors and future generations. Coming from a rather rational family, this has made me question my views and forced me to try to see things from another perspective.

Courtesy the artist

Turati: Mayra, what thought or sensation overtakes you when you realize this is not only about Ciudad Juárez, but that we live in a country where mothers with missing sons and daughters march every May 10, or that the very places you photographed continue seeing the disappearance of young women?

Martell: There is a book, Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future (1998) by Charles Bowden, with texts by Noam Chomsky and Eduardo Galeano, as well as images by press photographers from Ciudad Juárez, that explains very well the situation of Juárez and Mexico. It elaborates on the social decomposition none of us can escape. In Juárez, there were many warning signs around us, which nobody paid attention to because it was always about the neighbor, the poor fellow, the girl from the maquiladora [foreign-owned factory]. Nobody understood that if things were happening to people across the street, it would someday reach their homes too. Violence is expandable.

Turati: Maya, what advice would you give, if you could meet your younger self—that photographer who was only starting to capture the violence in La Merced or in Juárez?

Goded: That she should study philosophy, read about culture in general, because technique is learned quickly, but, in the end, photography is enriched by life and knowledge.

Turati: Mayra, what would you advise a younger Mayra who was just starting?

Martell: I’d hug myself so tight that I’d cast a spell of protection to last for years. I haven’t changed that much—it’s just that the little flame in my heart has been extinguished several times. But it always lights up again. And I would say to myself, I love you. That would have helped me in a lot of personal situations.

Read more from Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Translated from the Spanish by Enrique Pérez Rosiles. Visita gatopardo.com para leer este artículo en español.