A Land of Their Own

Anyone who has studied architecture’s histories knows that utopias are rarely, if ever, realized. The annals are littered with paper plans for radical homes never built or, worse, promised paradises—from Pruitt–Igoe in St. Louis to Abu Dhabi’s Masdar City—that saw the light of day and either failed their residents or only worked as intended for a fortunate few.

Yet, there are exceptions to every rule.

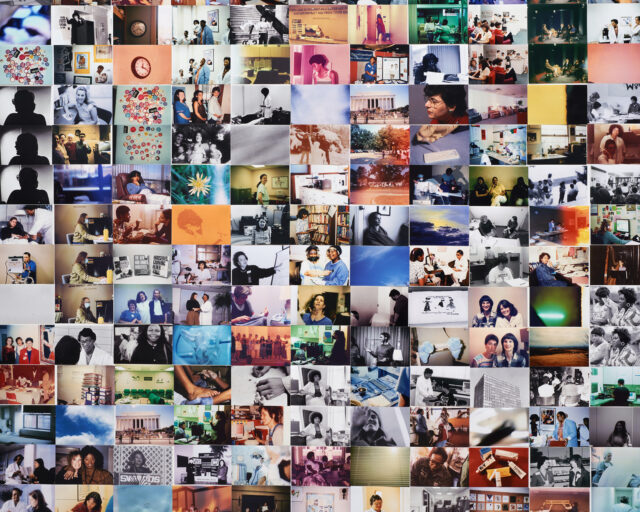

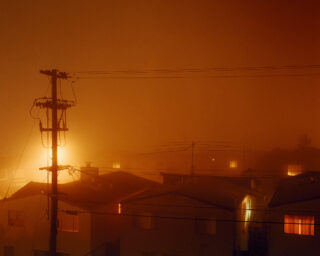

© the artist and courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art

It surprises me little that when utopia comes close to actualization, its architects are usually not men. One such breach, born of the radical feminist movements of the 1960s, came in the form of 1970s and ’80s womyn’s land collectives that created new paradigms of domestic freedom and kinship between lesbians denied those rights across the United States. Meadow Muska, a photographer, feminist, and master electrician, recorded land collectives that existed in her home state of Minnesota. Fresh out of her BFA at Ohio University, Meadow (who prefers to be referred to by first name) made work that chronicled the “beautiful, strong women, full of love and joy” that she witnessed at places like Rising Moon, a one-hundred-sixty-acre site in Aitkin, Minnesota. Her work was largely unknown until a 2019 exhibition curated by Casey Riley, Strong Women, Full of Love, was staged at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA).

Meadow captured a time when hundreds of women, most identifying as lesbians, imagined a radically different version of belonging, forming intentional, women-only, agrarian communities across the U.S. As women were usually paid less than their male counterparts in the workplace and unable to access the same credit as men, the womyn’s land movement burgeoned as they pooled their resources and purchased pockets of rural land. Rejecting traditional expectations around their reproductive capacities, the shape and design of the home, and women’s prescribed roles within it, they made room for their own desires and identities. They built physical and psychological hearths with their own hands, from the ground up, and recorded these revolutionary acts through photographing their lives, loves, and independence.

© the artist and courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art

For Meadow, as for so many of her generation, freedom to express one’s sexuality and personhood meant crossing a threshold both literally and figuratively. In 1972, aged twenty, Meadow found her way to a South Minneapolis feminist bookstore, where she met her first important romantic partner and publicly affirmed her sexuality. A photograph taken at the city zoo shortly after that meeting shows her smiling radiantly next to her girlfriend, Cydni James Irish, whose shades reflect the photographer, their friend Molly McCarthy. It is an uninhibited moment. Their faces are nestled close together and Irish’s Afro hairstyle is echoed in the curve of her partner’s raised parka hood. The composition conjures the signature style of New York Times wedding announcement photographs.

There is irony in this similitude. In the same year that Meadow met Cydni, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a local Minneapolis county clerk’s refusal to issue a marriage license to a gay couple. The nonchalance captured by McCarthy belied the daily reality of threats, harassment, and ostracization experienced then (and still) by LGBTQ individuals and communities across the country. While that case, Baker v. Nelson, catalyzed activists in the fight for equal access to the institution of matrimony, contemporary commentary on average American homelife more often focused on heterosexual couples trying to escape it, as evidenced by the ensuing spike in divorce rates, which peaked in the 1970s. Photographers were primed to document this dissolution of the nuclear family. LIFE commissioned photo-essays that drew back the curtain on varied domestic stories of separation, collective living, and birth outside wedlock, though they centered predominately heteronormative, middle-class, white protagonists. Wanda Adams, a thirty-five-year-old Seattle spouse and mother, smiled confidently on the cover of the March 17, 1972, issue under a headline in scarlet type: “DROPOUT WIFE: A Striking Current Phenomenon.”

But women were not “dropping out.” They were directing their expertise and energies to places and people they—not a husband, boss, or society at large—chose. And while reimagining home was an expansive project with heterogeneous outcomes, in many cases redefining domesticity took very concrete skills. Like Adams in Seattle, Meadow was active in her local chapter of Women in the Trades, a 1970s labor advocacy group that supported women working as independent contractors—the career Meadow turned to when she lost her job as a photojournalist after coming out. Meadow’s 1976 portrait of nine women in Eugene, Oregon, shows them collapsed together in laughter. They form a joyous frieze; their bodies read almost as one, hands clasped tightly atop one another. (A moment later, Meadow told them to “get serious!” so she could capture the shot for a skilled-trades grant application.) In a 1981 picture of one of the first residents of Rising Moon, River Brady, Meadow shows her subject bare breasted, a sawhorse in the background, and holding a tool whose end extends out of the shot, hard at work on a farm she rented in Osseo, Minnesota, where she raised goats.

Meadow recalled that women rode horses from Missouri and Wisconsin to get to these sites of freedom in Minnesota. Like her, many had lost their livelihoods, or family ties, after coming out. Some had experienced gender-based violence. “It was a huge deal to them—for everybody involved—to trust me that I wouldn’t use these images without consent,” Meadow told me. “It wasn’t just a snapshot.” To avoid confiscation or exposure of identity, she had her own basement darkroom and gave her subjects a copy of their photograph. Usually a 5-by-7-inch print, it was perfect for domestic presentation and, as Meadow put it, a way of “my sharing as they shared themselves.”

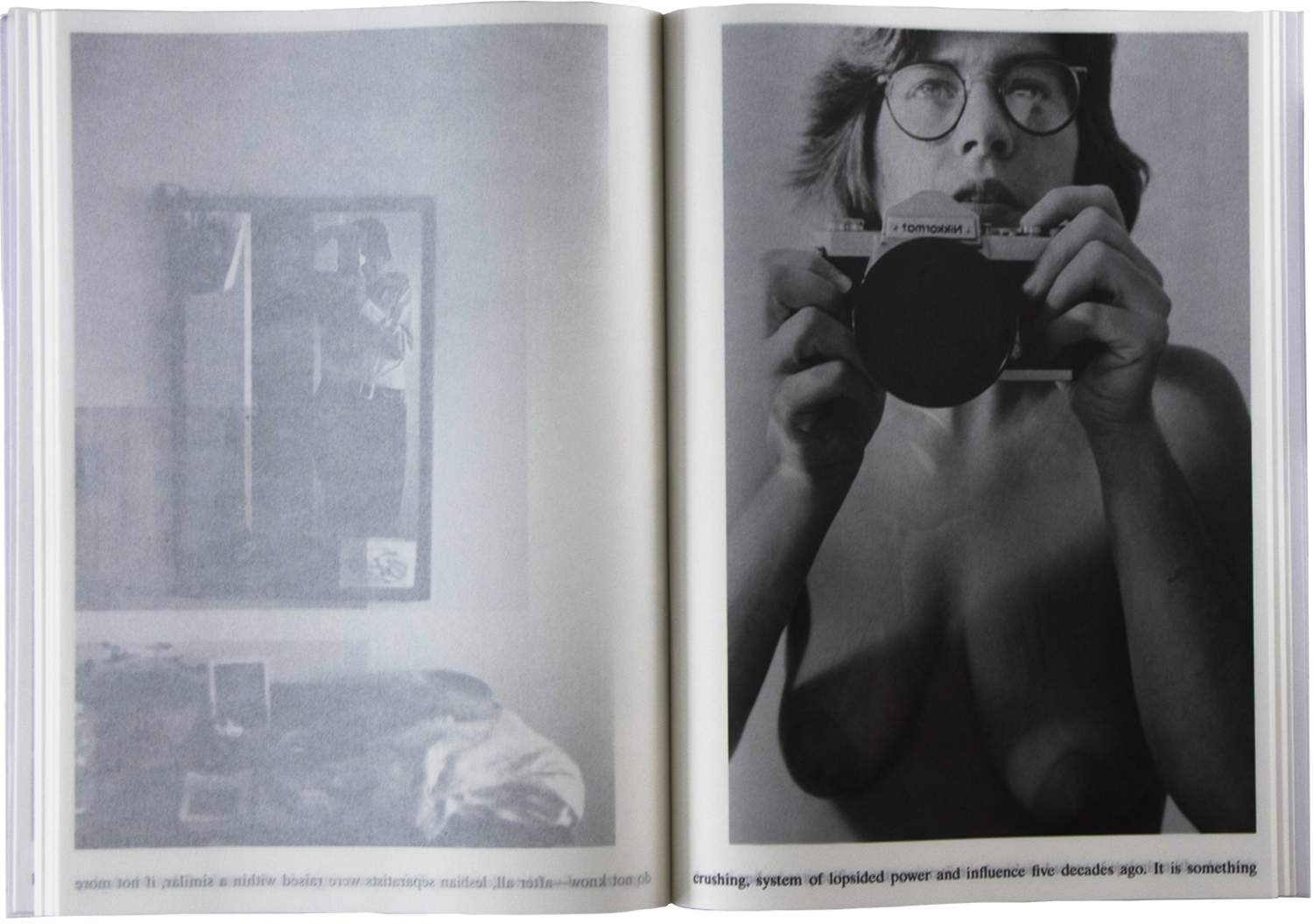

Meadow was not the only person documenting these rural inhabitants. Working from a generation’s distance, contemporary artist Carmen Winant has recently amplified the work of photographers from that era who made similar images. Her recent project, Notes on Fundamental Joy; seeking the elimination of oppression through the social and political transformation of the patriarchy that otherwise threatens to bury us, includes works by Tee Corinne, Joan E. Biren (JEB), Ruth and Jean Mountaingrove, Carol Newhouse, and Clytia Fuller. Part artist book and part historical document, Notes on Fundamental Joy gathers photographs that show circles of women sitting on the land, tending to each other with haircuts, and reimagining their lives through collective models of domesticity. They formed not only new spaces, but whole lexicons (menstruation → moonstruation / women → womyn / history → herstory) and last names. These photographers conducted workshops, “Ovulars” (a conflation of ovulation + ocular, against the seminar and its etymological connotation of “spreading seed.”) In the wake of feminisms that contested each other as fiercely as they did the systems of patriarchy around them, they photographed these spaces as proof of their will to self-determine. Winant’s opening lines set out these stakes clearly:

Is it possible to leave everything behind? Is it possible to begin again, outside of and

beyond every system of living you’ve ever known, reinventing what it means (and

looks like) to exist as a body and its soul, on the land?

And yet, whose utopias were these? Winant’s book contains an essay by San Francisco Bay Area writer Ariel Goldberg that meditates on who gets to create and define spaces of their own. Goldberg parses the relative nature of difference and separatism as both a form of affirmation and one that demarcates others with even less privilege, agency, or defenses against exclusion. They wonder where trans and bisexual, poor, and nonwhite identities fit within womyn’s utopias, historically and today. And, in the portrayal of predominately white women, “how separatism functions when it has not dismantled whiteness as its norm.” These were questions that many of the photographers, including Meadow, asked of themselves at the time. And in re-presenting images taken almost fifty years ago in a book or museum—a paragon of exclusionary space—Meadow and Casey Riley in the exhibition at MIA, and Winant in her artist book, were all painstakingly careful about seeking permission from their subjects, thinking carefully about who benefits from such recirculation. Is the act of making a home always inherently exclusionary of some, even as it seeks to sow inclusion?

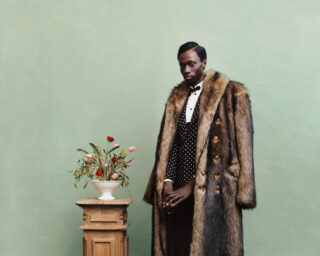

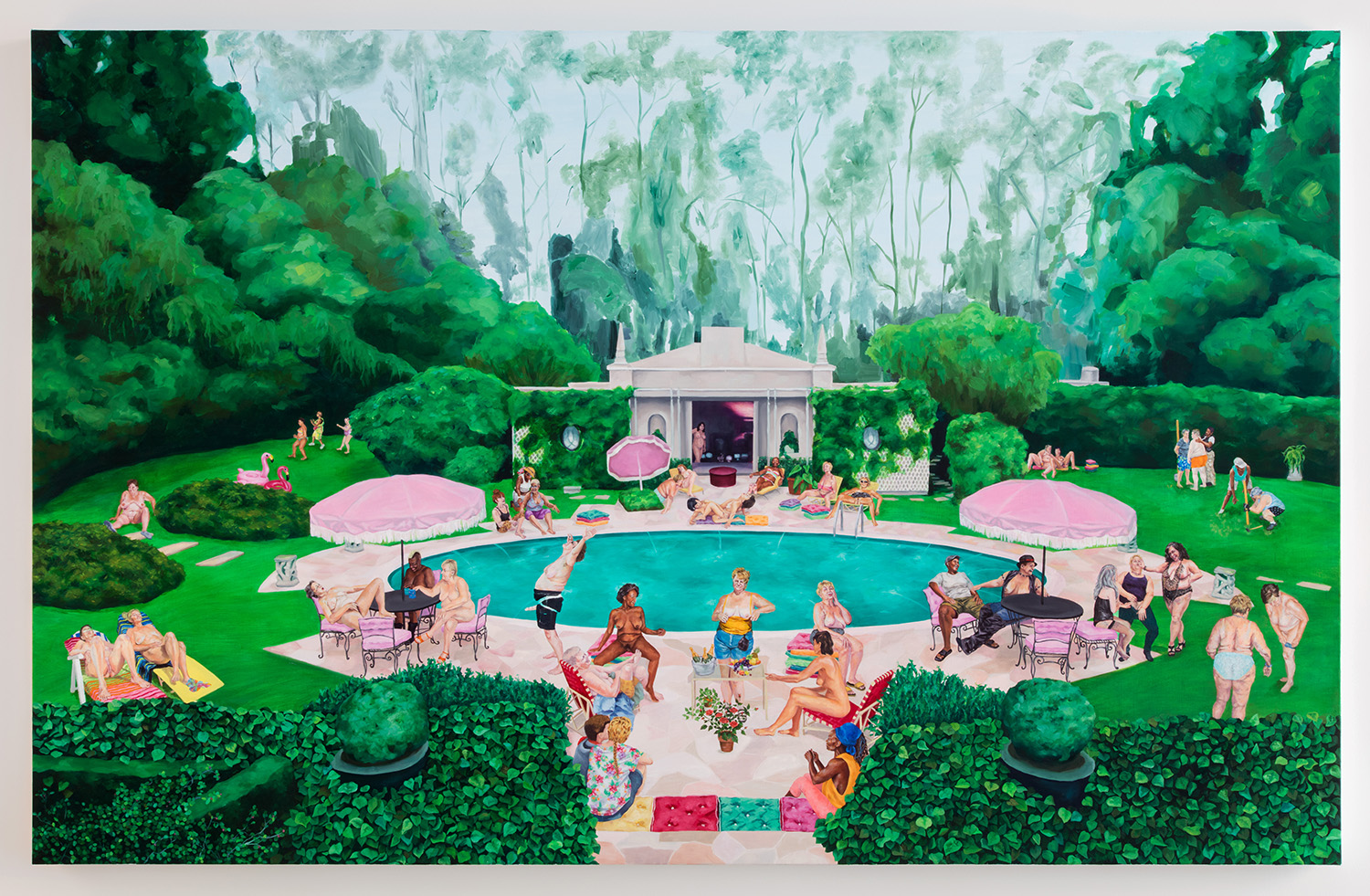

Courtesy the artist

The week after I stood enraptured by Meadow’s exhibition, I visited Samantha Nye, a young painter and filmmaker, in her basement studio on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Nye, like Winant, reaches back into the historical archive, drawing primarily on two celluloid sources: 1960s Scopitone films (precursors to MTV, in which scantily clad white women grin and grind to pop hits) and Slim Aarons’s mid-century jet-set scene photographs of, in his formulation, “attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places.” In her video work and canvases, Nye casts elders from her own family and queer communities with whom she collaborates. She inserts them into these historic scenes to create fantasies that function as an imaginary future for spaces like Rising Moon, “bound by the concept of chosen family” in a vision that is age and trans inclusive. Like Meadow and her generation, faced with suburban conformation, for Nye the photograph is a site for artistic subversion of homogeneous and oppressive worlds that socialize women to expected patterns of desire and domesticity. In her attempt to image queer kinship, Nye acknowledges its “beautiful parts, the prickly parts, the radical parts and the parts that have long needed fixing.” The parts, in other words, that exist in most families, and most homes, and most portraits of domestic life, however they are built, and whomever by.

Read more about photography and the domestic realm in Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home.”