How to Map a Territory that You Don’t Own

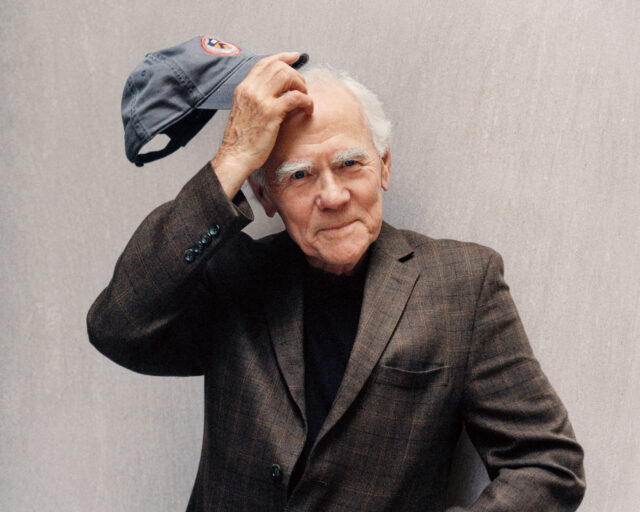

Mitch Epstein discusses Standing Rock, the American flag, and the moment he saw Mount Rushmore cry.

Mitch Epstein, Standing Rock Prayer Walk, North Dakota, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Since the mid-1970s, as one of the first artists to significantly embrace color photography, Mitch Epstein has often depicted land and our relationship to it, whether in his early cross-country trips, or in his 2009 book, American Power, an epic chronicle of our attempt to wrest energy from the Earth, or in his meditations on the clouds, rocks, and trees of New York City. He traces the genesis of his most recent project, Property Rights, currently on view at Sikkema Jenkins & Co. in New York, to the resistance movement that took hold in late 2016 in the wake of the US presidential election. Yet he also refers to the artistic influence of multiple works outside of photography, including Arthur Jafa’s film Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death (2016). Property Rights, though it focuses mostly on threatened landscapes, is part of an established trajectory mapped out over decades of work, fully evident in Epstein’s latest photobook, Sunshine Hotel (2019), which threads recent photographs made as part of Property Rights into an anachronistic sequence that heightens the connections between new and archival photographs.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

I have followed Epstein’s work for many years, but we first began speaking in early 2017, after I returned from a series of trips to the Indigenous-led resistance camps fighting the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. Epstein was preparing a visit there, in the wake of President Trump signing orders to advance construction of the Dakota Access and Keystone pipelines. Our conversation would continue over the course of many months, studio visits, and a story collaboration for which we both returned to Standing Rock to follow a four-day prayer walk led by water protector and activist Nathan Phillips. A photograph from that prayer walk, depicting a continuous human line traversing a snowy roadside and bisecting a farm road that leads directly to the Missouri River, is featured in the exhibition alongside images of tree-sit structures high in Pennsylvania white pines, the prehistoric ecology of the Ironwood Forest in the Sonoran Desert, a woman peering through a prototype of the US–Mexico border wall, and others we spoke of here.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Rebecca Bengal: The earliest photographs you made as part of Property Rights are from your first visit to Standing Rock. Where did the project begin for you?

Mitch Epstein: The motivation, or the insistence, to go to Standing Rock was the result of having lived through the election and Trump’s inauguration and going with my wife, Susan Bell, to the Women’s March and feeling this surge of resistance, and also to step out into the middle of something that was so divided, at least as it appeared to me.

I had followed Standing Rock in the media and I wanted to go in the fall of 2016, but I had an injury. And then when Trump did an about-face there, I decided I had to go. I went with the expectation that I would make some pictures, but I wasn’t thinking about the long game of making a project. I just went with an open mind and eyes, and also a lot of warm gear because it was probably some of the coldest weather that I ever experienced—the real temperature was ten below and windy when we landed in North Dakota.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

When we arrived at the camps, it involved a certain amount of negotiation to be welcomed as a picture maker, but that led me to one of the most profound experiences of being there, which was meeting elders—matriarchs, referred to by some as grandmothers, repositories of deep knowledge, who were in the face of these adverse conditions. I did some video interviews. It was listening to them, to their stories, that encouraged me to think in ways that I hadn’t about some of the historical imbalances, the wrongs. Those conversations and the real righteousness of those voices stayed with me and enabled me to begin to think in a more extended way about how compelling and challenging it would be to do a piece about land in America that would hopefully bring about some new way of looking at it, this notion of who are we to think we can claim ownership of land?

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: You recently Instagrammed a research map with pins marking the sites all over the country where you plotted potential locations for these pictures. How did the project begin to evolve for you after Standing Rock?

Epstein: I have a great studio manager, Ryan Spencer, and we’ve brought the process of research into the studio in a way that provides a very broad road map to thinking about what might instigate something for me. We learned about a community in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Lancaster Against Pipelines, which was fighting the construction of a natural-gas pipeline. I reached out to a man named Mark Clatterbuck, and I was expecting to have to go through the kinds of high-stakes visits that I did at Standing Rock to even be admitted to make a visit there, and he just said, “Oh yeah, come on down.”

As soon as I got to Lancaster, what was so interesting was this community that was gathering on a Saturday on this farm and meeting to discuss what options there would be to protest. Many of them were subject to having their lands taken over by eminent domain; these people would otherwise be playing tennis, at the farmers’ market, and yet they were there because they felt strongly. They were not extreme; they were not typical activists. They were like me. I was really touched by that, and I began to see how I could make work in Lancaster. I probably made seven or eight trips down there over the course of a year, and then I spanned out to do much broader research that was more continental in scope.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: There’s a wonderful picture of Ashton Clatterbuck—a young activist and the son of Mark and Melinda Clatterbuck—who was arrested during one of the Lancaster actions. You photographed him locked to a tree as if he’s also embracing it [Ashton Clatterbuck, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 2018].

Epstein: I had gotten to know the family for two years, and I was very moved to see the ways in which these tools of resistance were used. This lockdown device was handmade and weathered, and I wanted to make some pictures outside of the actual actions that showed the relationship to those tools, the urgency of that engagement.

We weren’t near a construction site, but all I had to say to Ashton was, “Put yourself in that place where you were when you were arrested.” The way it gets distilled down to its most simplistic form, to lock himself to a tree, was such a perfect metaphor for protecting nature. He was so invested emotionally. He’s at the heart of his adolescence, but he also has the look of an adult. He’s taking on the responsibility of an adult. He’s a bit like Greta Thunberg in that way.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: Trees and rocks, respectively, were the subjects of two recent bodies of your work, and they appear here in these pictures, perhaps most notably in this remarkable photograph of Mount Rushmore, drenched in rain and fog [Mount Rushmore National Memorial / Six Grandfathers, South Dakota, 2018].

Epstein: I think even photography that’s engaging with the world in a representational, descriptive way involves a kind of appropriation. For me, the question was how to take something that’s so imaged and iconized and contrived and bring some kind of fresh reading to it.

When I was twelve, I went on a cross-country trip that included the Badlands, and I remember going to Mount Rushmore and standing in the place the Kodak sign told you to stand and make this perfectly framed, very idealized picture. In 2018, when I made a trip to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, it was interesting because people would either say to me, “Oh don’t go to Mount Rushmore, or we’re not going to talk to you anymore,” or other people would say, “You must go there.” In the end, I made what was sort of an enforced pilgrimage for a white guy. We got a permit from the National Park Service, but after three days of rain, finally we decided to just go scout it.

In this upper altitude in the Black Hills, you have this variable weather, and we were fortunate because the monument itself was coming in and out of cloud cover, and because of the rain, the area wasn’t so trafficked. Then I looked closely at the faces of our presidents, and it was stunning to see the water running down their faces. I mean, that’s pretty straightforward. But it was after our permit time, so we snuck in. You know, I’ve seen North by Northwest; you’ve just got to be clever, right? It’s not like an 8-by-10 is so big, but we had gear and so on; we used our tarps like ponchos. We found a bit of cover from the rain by the elevator that gave a good vantage.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: Which I love. And I’m just struck by the fact that although we’re looking at rock—this very photographed and controversial rock—here’s so much that is activated in this picture, so much interplay and surprise here.

Epstein: I think the photographs of mine that endure are ones that engage with time in multiple ways. They’re absolutely of that present that they’re made in. But they have this potential to reference the past and exploit or incorporate it into the tableau of the picture, and also to speak prophetically to the future. Here, when I stepped back, I realized that I could frame these mountain peaks and these carved stone faces, which were a kind of profound violation of the sacred Lakota site known as the Six Grandfathers. The forms themselves are very distinguished, like certain Chinese landscapes. And I wanted to see and to make dead center all the shot rock that was a consequence of the dynamite; all of this is really at the gut of the picture. And at the same time, you see these burgeoning, fertile fir trees.

Bengal: The trees have an almost lifelike energy, as if they’re running up the mountain.

Epstein: They’re shooting up out of the landscape. You’re confronted with the evidence of what it takes to carve a sculpted form like that into stone. But also, the atmospheric quality of the fog alludes to the fact that, in time, these faces are not going to be here anymore. They’re going to erode. This has been a gift in my later work: I see how small I am, how small we all are, and that’s humbling.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: And as talk of the president’s border wall and threats to immigration rights escalated, you began to photograph in South Texas and Arizona.

Epstein: I was compelled to spend time in border regions, to look at the cultural exchanges that was very unique to those places: people who were operating under fear and extremism and wanted to protect what they thought would be threatened by immigration. It was not so simple, and also not so simple to try to picture these things.

I made this photograph of a bunk bed in El Paso in 2017 [Refugee Halfway House], when it wasn’t as contentious at the border as it is now. But this was a Catholic mission—this was a place where people could have sanctuary while they awaited their asylum trial to gain immigration status. What spoke to me about this was how it relates to everybody. Everybody deserves and needs a bed, with a pillow and a sheet and a blanket, and a towel. These are the things we take for granted, and they’re so elemental, yet also personalized through the palette of these items and the photograph itself. When you imagine the passage people take, this near-death experience to get into the United States, to have a bed waiting for you.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

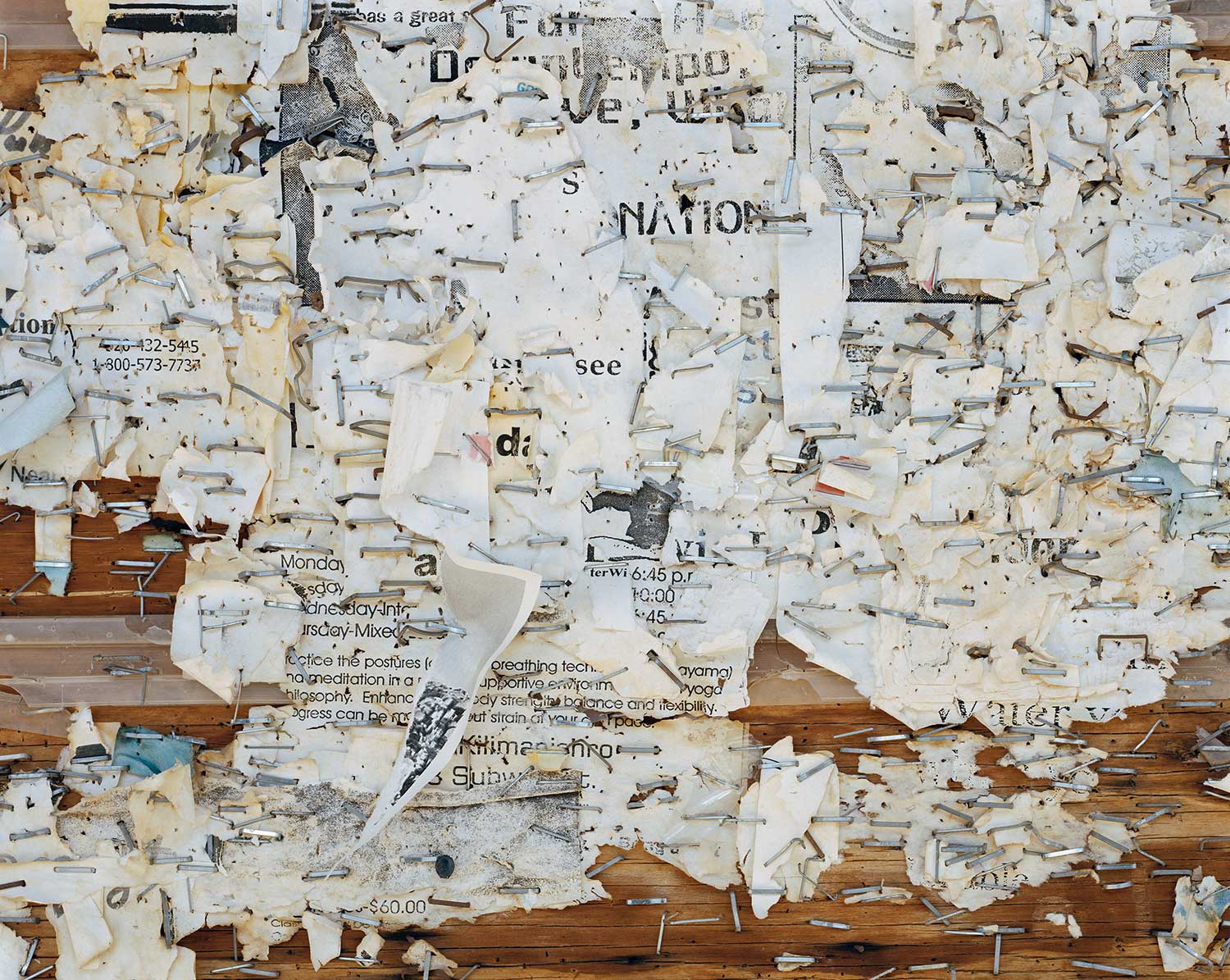

Bengal: There are no people in the picture, but there’s definitely a human impression in the folded towel and the bed made with the flowered sheet. And you see the impression of humans here, too, in all these torn and covered messages [Bisbee, Arizona, 2017].

Epstein: I was driving from Tucson on my way to a site right on the border, and suddenly I drove into this place with a lot of visible prosperity, Victorian houses, a whole town seemingly growing out of the hillside. A few miles down the road, I pass a giant copper mine. There was a clear equation between the big hole in the ground and this town that was clearly built as a result of this mine. I stopped to make a couple pictures, and then I went to a co-op grocery store to get a drink, and there was this message board. I was just struck by the kind of inherent violence of the way the staple gun was holding this palimpsest of papers to the wall. Then I realized there was this accidental confluence of very poetic but also symbolic words that spoke to the moment: nation, see, meditate, water. For me, it suggested a kind of mapping. And again, back to property rights, the consequence of owning land, and using it or neglecting it, is that it becomes battered.

I also think that in photography, the most surprising and thrilling pictures are often the ones that are made out of nothing. So to me, it was also something, especially in this era when we are so married to our screens, to look at paper photographed with film.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Bengal: The American flag is represented in several of the pictures—“an exclamation point,” you’ve called it—in your picture of Mount Rushmore, upside down on the back of a prayer walker at Standing Rock in 2018 [Standing Rock Prayer Walk, North Dakota, 2018], and most prominently here, also at Standing Rock, but as seen during your first visit in 2017, against the snow and this very blue sky [Veterans Respond Flag, Sacred Stone Camp, Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, North Dakota, 2017].

Epstein: It’s these punctuating details that often lend ballast. This flag was a kind of technical triumph. It was up high and on a ladder; I used a longer lens than I usually do, and it made it an object that’s more sculptural. An 8-by-10 lens only stops action at 1/125th of a second, so you don’t know quite what is going to result. But there’s something very buoyant about the way the flag is catching the light. There’s beauty in distress.

Bengal: I also see it as a positive sign—of resistance taking hold, the wind visibly stirring it up.

Epstein: It’s quite forceful. It really holds its sky.

Mitch Epstein: Property Rights is on view at Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York through October 5, 2019.