Everything is Light

Mona Kuhn, AD 7809, 2014, from the series She Disappeared into Complete Silence, 2014

© the artist

Los Angeles seems literally made of light. Most days, an unbroken blaze shines down from cloudless skies where palm trees casually sway, casting every detail of the city’s surfaces in forensic focus until they eventually disintegrate into the pink-hued explosion of sunset. Even as the light fades, neon signs illuminate shop fronts and sidewalks, parades of hazy red-and-white orbs make freeways glisten, and, viewed from the surrounding hills, the whole sprawling mass shimmers quietly. The bright lights of movie theater marquees beckon toward projected illusions inside and remind us that cinema chose Hollywood, in part, for its year-round promise of gleam. As the film industry flourished in the 1910s and ’20s, architects flocked here too, entranced equally by the city’s special quality of light and by the avant-garde spirit of freedom and inventiveness that inspired new ideas about “modern” living.

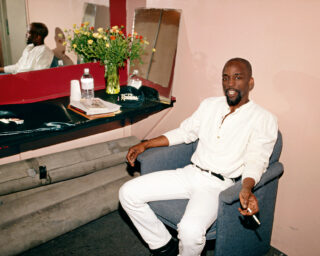

Mona Kuhn, AD 6046, 2014, from the series She Disappeared into Complete Silence, 2014

© the artist

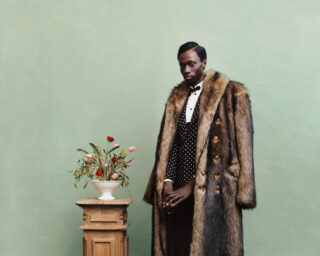

Mona Kuhn, a German-Brazilian transplant to the city, often works at the intersection of light and architecture. In her series, She Disappeared into Complete Silence (2014) (which draws its name from Louise Bourgeois’s first monograph), the lines and shapes of an anonymous house frame images of a desert setting. A sharply angled overhang looks out toward a graph of mountain ranges and cuts a black triangle across a swath of sky. Watery reflections undulate beneath a room’s blurry scaffolding, and refracted doorways lead to the arid earth outside. Mirrorlike, silvery folds and a spectral figure recur, beacons in an ominous landscape. Shot in a modernist structure built by architect Robert Stone outside Joshua Tree National Park on the fringes of LA, Kuhn’s images are mirage-like, visions borne of a thirst for otherworldliness.

Mona Kuhn, AD 6705, 2014, from the series She Disappeared into Complete Silence, 2014

© the artist

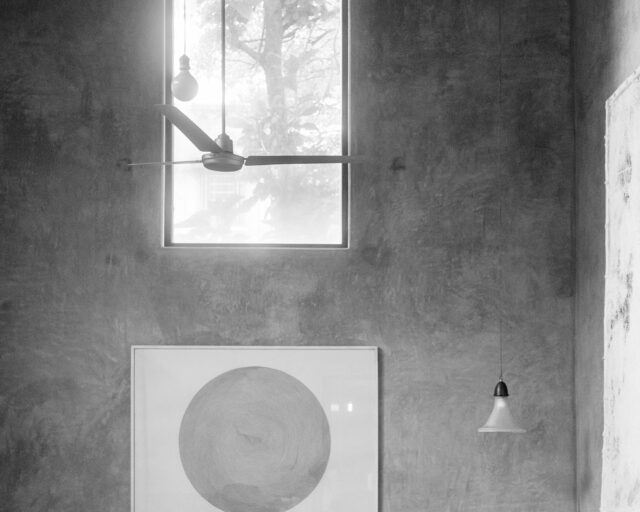

For Schindler House (2015–ongoing), Kuhn turned to a more specific architectural and social history. Designed and built by Rudolph Schindler, the West Hollywood house was a masterful experiment in communal living (intended for two couples), with private rooms and shared spaces dispersed around a pinwheel axis. Completed in 1922, it quickly became a place for working out other modernist ideas, as well as a hub for intellectuals and bohemians. Kuhn’s pictures of the house evoke the moment it was imagined, in soft, veiled vignettes. Like walking through a dream, the house appears as a memory of some lost, ideal past, both haunted and romantic. Yet at the same time, the images are unfinished and tentative, sketches for a potential future not quite realized.

Mona Kuhn, Schindler House #2, 2018, from the series Schindler House, 2015–ongoing

© the artist

Read more from Aperture issue 232, “Los Angeles,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.