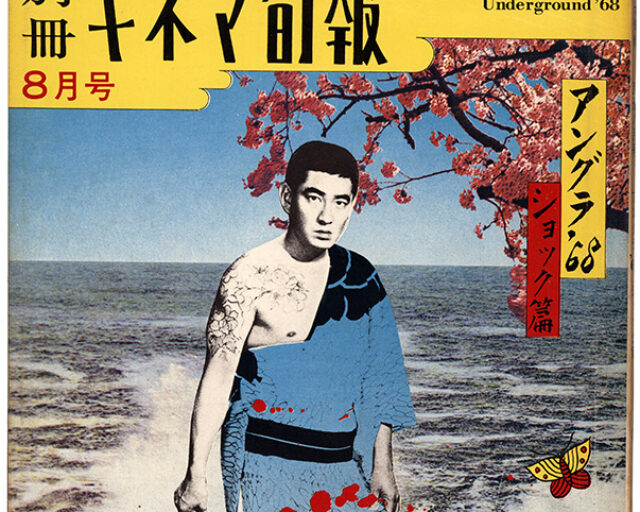

The Endless Outer World

Daido Moriyama speaks about his Provoke days and capturing the streets of Tokyo.

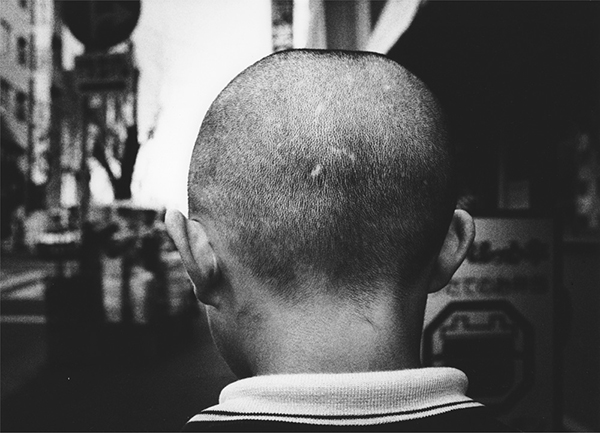

Daido Moriyama, from the series Hunter, 1972

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

By the time Daido Moriyama joined the magazine Provoke for its second issue, he had already perfected the art of the accidental image. Embodying the revolutionary spirit of this late-’60s collective, Moriyama has since become one of the world’s most recognized photographers. His blurry, angular photographs of Tokyo’s Shinjuku district challenged conventional notions of photography. Moriyama’s early mentors included the legendary photographers Shomei Tomatsu and Eikoh Hosoe, but it was Takuma Nakahira who proved to be his greatest collaborator and closest friend. Decades on, Moriyama has continued to photograph Toyko’s streets using a small, handheld camera, inspiring generations of image makers. Tsuyoshi Ito of A/fixed spoke with Moriyama about his time with Provoke.

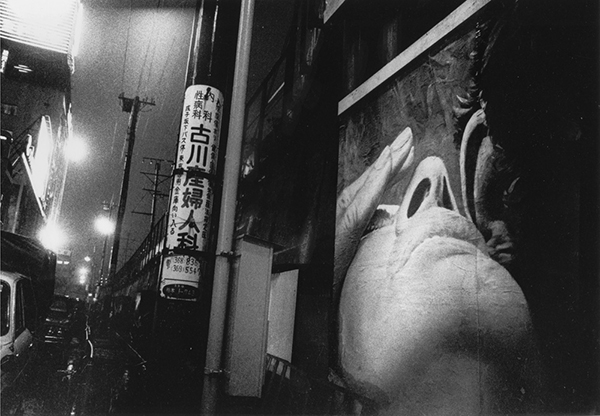

Daido Moriyama, from the series Hunter, 1972

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Tsuyoshi Ito: What drew you to participating in Provoke in the first place?

Daido Moriyama: Takuma Nakahira invited me after the first volume had already been released. Without his invitation to join, I likely would not have been involved. We were best friends and I had a great fondness for him. So rather than being interested in Provoke itself, it was more of an interest in him that made me want to join.

Ito: What was the energy like when you joined for the second issue of Provoke?

Moriyama: Provoke was a lot of fun. Everyone had the similar ideologies about photography, but the way each person expressed it was very different so we all stimulated each other. Since Provoke came at the end of the ’60s, much of it was very political. I had no interest or opinion about politics, so I did not partake in political movements and demonstrations. I focused instead on the need to reform photography. Provoke provided me with comrades.

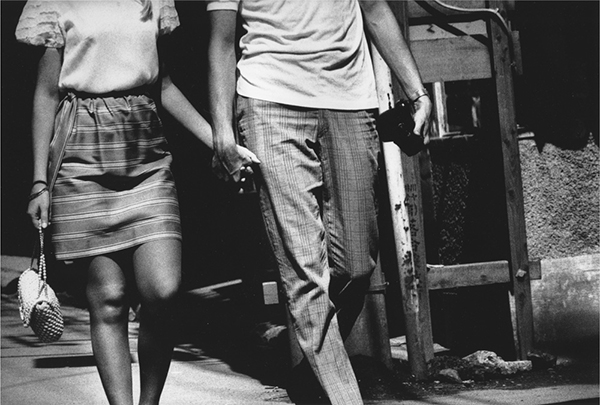

Daido Moriyama, from the series Hunter, 1972

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Ito: How did you get acquainted with Nakahira?

Moriyama: I met Nakahira when he was still an editor working for Shomei Tomatsu, so it was through Tomatsu’s projects that I was introduced to him. Compared to me, Nakahira had an opposite stance on things. Rather than seeing him as a charismatic photographer, I saw him as my only rival and also my only true friend. Never, before or after him, have I had a relationship like that with anyone else. So I thought that if I were doing something with him, then surely it was going to be fun.

Ito: How was it working with Yutaka Takanashi, one of the other key figures behind the magazine?

Moriyama: It was not a daily occurrence for us to see or hang around each other. Our ideologies on photography were also slightly off, but at the root we had a sense of consciousness of each other’s work that tied us all together.

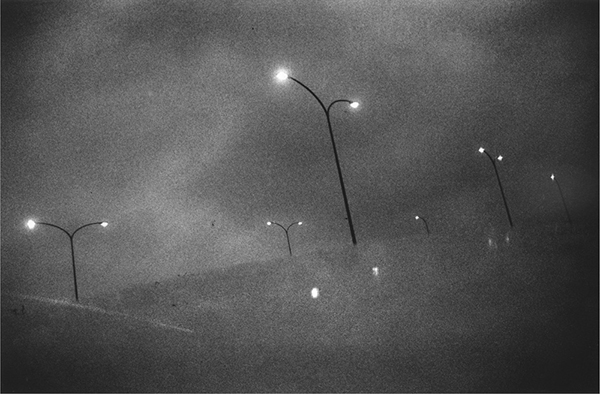

Daido Moriyama, from the series Hunter, 1972

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Ito: What was your reaction to Provoke breaking up after the third issue?

Moriyama: When the members of Provoke got together to discuss disbanding, I was the only one who was against it. I questioned why we were doing such a thing because we hadn’t accomplished anything yet. I understand now that perhaps we had reached our limit, but at the time that reason did not satisfy me. It made me question what three volumes were going to accomplish and what it could possibly provoke. But as I said earlier, I got to spend time in meetings with people I had never worked with, and being exposed to them was very stimulating. I am still in the mindset of my Provoke days.

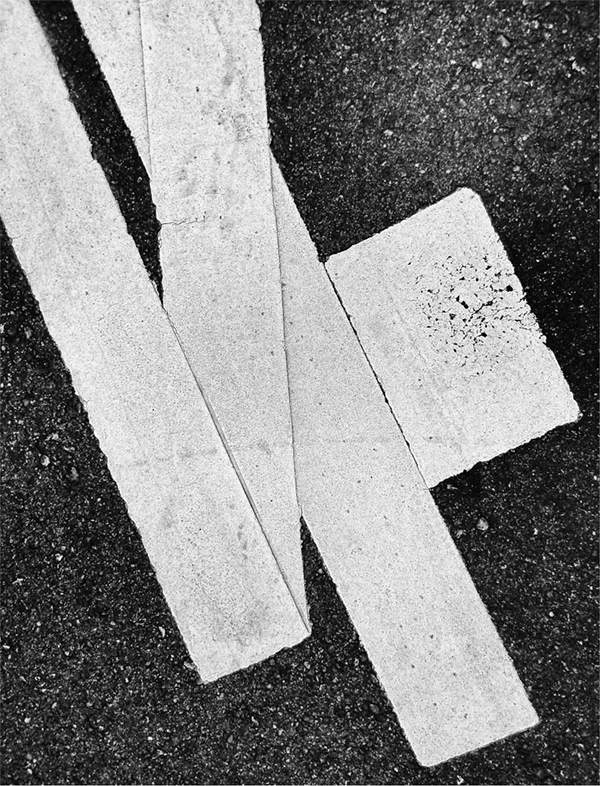

Daido Moriyama, from the series Light and Shadow, 1982

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Ito: You mentioned that you got your start in graphic design. What kind of relationship does that discipline have to photography?

Moriyama: When I was younger I did not think about what graphic design had taught me, but as I grew older I realized that it was actually very important. This was particularly clear during the construction of a photography book. It made me realize that there was a part of me that was still curious about design. There is part of me that wants to create something for the graphic aesthetics, rather than for the story. Being exposed to graphic design from countries such as America at a young age played a major role in shaping my photography.

Daido Moriyama, from the series Light and Shadow, 1982

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Ito: Shinjuku was the center of Japanese arts culture in the 1960s. Did you enjoy being part of its atmosphere and people?

Moriyama: In the ’60s, there were diverse people in Shinjuku, but I was never one to hang around with many people. Shinjuku was a labyrinth, and what it had to offer meshed very well with my personality. It was a center of chaos that was both stimulating and fun. As a street photographer, I was trying to capture the people and the distinctiveness of the time, but simultaneously it was the city itself that was my focal point. In the end, I was trying to capture an essence of myself. All photographers, no matter what their concept, are all just trying to photograph themselves in a sense.

Daido Moriyama, from the series Dog and Mesh Tights, 2015

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Ito: How do you view the importance of the photography book?

Moriyama: Books are essential to photographers. I do not go out to shoot with the thought of finding material for my next book. I travel streets to find reality. I still have moments when I’m photographing and wondering why I’m taking pictures and what they mean to me. As a result, my photography books turn into a jigsaw puzzle. But unlike a normal puzzle, there is no completion to my works; they do not perfectly fit together. For me, that is what a photography book is. There’s no such thing as completion; rather, the last puzzle piece is contemplation about the next book to come. The process of asking myself questions of why I do what I do is the process of making books. Each book has no correlating theme; it just captures the endless outer world.

A/fixed’s inaugural publication, Provoke Generation: Japanese Photography, ’60s-’70s is now available.