A New Documentary Turns the Lens on Robert Frank

In Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, Laura Israel delivers an intimate portrait of the artist who revolutionized photography with his trenchant 1958 book The Americans. Israel, who has worked with Frank since the 1990s, recently spoke with Aperture about the making of Don’t Blink, which opens this week at Film Forum in New York.

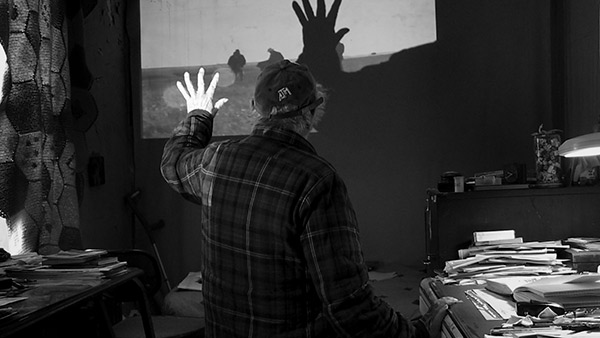

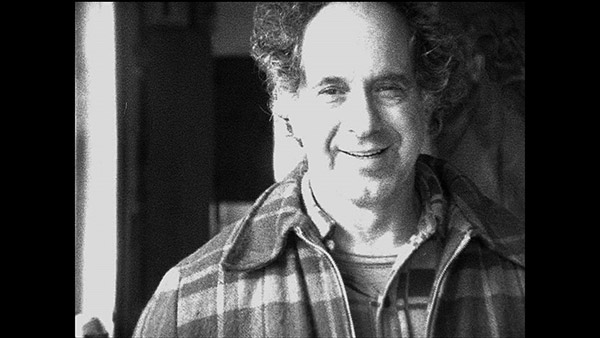

Robert Frank in Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph: Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Nicole Maturo: You’ve worked with Robert Frank on his films for a long time. How did you first meet him?

Laura Israel: It was through Run (1989), a music video for New Order. I used to edit a lot of music videos and a friend of mine who worked for Factory Records and New Order told me on this one I’d be working with Robert Frank. I remember the first day Robert came to my studio. At that time, we used to work in tapes, which you had to rewind and fast forward. It got really boring. So we used to make these little selects. I turned around to Robert and I said, “Once we make these selects, are we going to want to go back and change our minds? I’ll set up for that.” And he said, “No. Once we make a choice, it’s fate. First thought, best thought. We don’t go back. We only move forward.” And I remember thinking, This is my kind of director. That’s one of the things that’s so great about working with Robert: he’s so decisive. I admire that.

Also, I’m a big postcard collector, so after we worked together for the first time, whenever I got a good postcard, I would walk past his house on my way to my studio and I’d just throw a little postcard and a note in the door. And I think, in the end, that cemented our friendship.

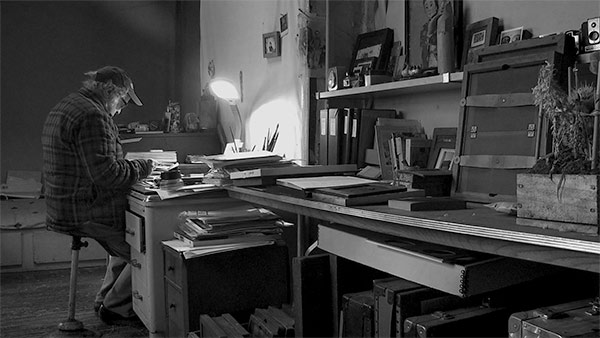

Still from Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph by Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: Frank is a postcard collector, too.

Israel: I didn’t even know that he collected postcards. I had some really good ones that I had been saving up. There was one in particular of a flamingo, beautifully hand painted. And that was one of the first ones that I put in his door. A few years later he came out with a book called Flamingo (1997)—it wasn’t based on the postcard, it was based on this photograph he had taken of a flamingo in a bottle. But it was little things like that that were kind of like fate, for both of us.

Robert Frank in Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph by Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: Frank is notoriously anti-fame. Did this make it difficult for you during the making of the film? How did you convince him to go in front of the camera?

Israel: It was a little odd for me because I’m so used to sitting next to him, rather than sitting in front of him and putting a camera in his face. But I also told him it would be a really small crew. We kept the crew down to three people, which was really difficult under those circumstances, but we thought it was important because we were going into his house, going into his life. It was important we that we tread lightly. And sometimes we went there and we said, Oh, you want to take a break, and we all had tea and cookies and hung out. And I found out later on that that’s how Robert got the Rolling Stones to agree to Cocksucker Blues (1979): he said he would only bring one other person to shoot. The other thing that I did was I invited friends of his, so it was more of a conversation. So Robert and his friend Ed Lachman both look at the book together, or we go out on these photo trips so it’s more of an activity. And it was more fun that way. I hope it comes out in the film how much fun we had shooting the film.

But very early on we found that he didn’t take direction very well. He kept me on my toes, which made the shooting more organic. It was also a little nerve-racking to have three different plans for every day we shot. But I know why he did it. He did it so that it didn’t become one of those really staged interviews.

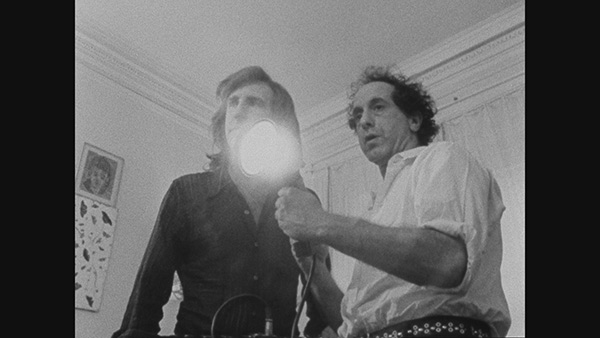

Still from Robert Frank’s film About Me: A Musical, 1971

Maturo: I was curious to see how the film handled the tragic loss of Frank’s children, Andrea and Pablo. When did it become necessary to include these details so that we can understand Robert Frank the man vs. Robert Frank the artist? Is there even such a divide?

Israel: One of the biggest strengths of Robert’s work, and people have remarked about it, is his embrace of creative work as the antidote to personal tragedy. I hope that comes off in Don’t Blink. That’s one thing that I’ve really learned from Robert: your life and your work can go together, and you can actually use your work to really help you through a lot periods in your life that are difficult. I think that’s what he was trying to say, after Andrea died, with Keep Busy (1975); that was the theme of that period of his life. He had to keep moving and keep working.

That was the hardest thing in the film to edit. I ended up using Robert expressing it through his work quite a bit because those are his innermost feelings, which are more poignant than someone sticking a camera in his face and asking, “How do you feel about this horrible thing that happened to you?” His work really expresses it much better.

When it comes including him directly talking about it, less is more. In a documentary, the most poignant thing that someone says is good to include. It hits me every time I hear Frank say, “Maybe to be in Mabou, it was more difficult to deal with Andrea’s death.” I know it’s this cold, lonely place and he’s in the middle of nowhere and going through that loss. It conjures up a feeling in me that is probably similar to the feeling that Robert had. I hope that I could do that with the film—make people feel what Robert was feeling. Not just have them hear what he was saying, but also to feel it in the film through the visuals. Which is what he tries to do with his photographs—to really convey what he’s feeling through his photographs not just portray what he’s seeing. I think that’s more in line with the feeling of Robert.

Detail from contact sheet, 1971. Photographs by Sid Kaplan

Maturo: Throughout your film, the use of jump-cuts is reminiscent of Frank’s filmography. Was there a particular Frank film that inspired your editing?

Israel: My editor, Alex Bingham, and I envisioned the film in three parts, and it had to do with Robert’s work, so I tried to have the film change. There was the more formal work, The Americans, black-and-white, very beautifully composed, very rough around the edges but also kind of lush. Then there was the period where he started to get into filmmaking but it was still film, it wasn’t video, and he also started scratching and painting words on photos and negatives. From the 1980s onward, he started shooting with polaroid, Super 8, and video cameras more often. The work sometimes resembled a personal diary, especially when he used his own voice to narrate. So I tried to see each part a little bit differently within the editing.

I had worked with Robert on The Present (1996). We had talked about editing the film as if you’re rummaging through drawers, looking for a photograph, or looking through old correspondence and memories. And you’re looking for something, but along the way you find other things that you’re looking through, so it’s seemingly random, but actually is has order. That’s what I was thinking about as the motivation of Don’t Blink as well. The other thing I tried to convey, which is true to Robert’s spirit, is the feeling of traveling along a road and then take a little detour but return to the road again, only to detour again and then go back. Nobody gets completely lost because of the signposts, yet you can take a little detour. That also was my motivation for the editing.

Robert Frank in Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph by Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: Many photography students are surprised when they learn that Frank gave up photography for a time in order to devote himself to film.

Israel: That was hard to portray in the film, but I understand why he did it because if you look at the sequencing of his work, as in the series From the Bus (1958), you can see he was practically shooting film, everything was movement, everything was this caught moment that was just about to move—you got this feeling he was going to move into film. That would be the natural next step. But also he has said, “I love difficulties and difficulties love me.” I think it was more difficult for him to pursue film. There’s one part of the film, it’s black-and-white footage from Frank at a conference at New York University in 1971. People were really giving him a hard time because he wanted to show his films, and they wanted to talk about The Americans. And he got really visibly annoyed with them. He said, “At least I’m trying to do something new and different, I’m not resting on my laurels. I’m not doing the same thing over and over again, I’m looking for something new.” I really respond to that, and I really respect that about him.

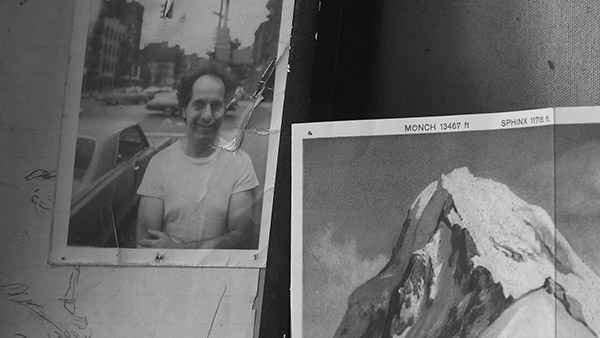

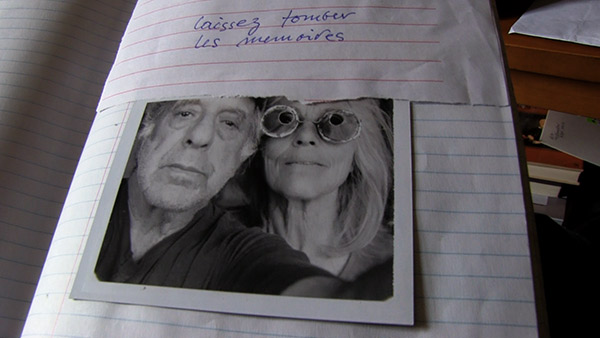

Robert Frank’s photograph of himself and wife, June Leaf, from Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: What’s the essential film that every Frank fan should see, a primer for his cinematic style?

Israel: Well it has to be Pull My Daisy (1959), although I have a certain love for the documentary shorts because they have a personal quality about them that I really like. The diaristic quality about the videos—it’s something that I really respond to. I can’t pick one, but I can say Conversations in Vermont (1969) is also a film that I really love; Me and My Brother (1969), I think, was really the first music video ever made. Pieces of that are so groundbreaking. I started out working in music videos and I saw that film and I was like, Wow, those are techniques we thought we were discovering and Robert had already done them. Like running the film back in the camera, there’s some amazing stuff in that film, and there’s some amazing stuff in Pull My Daisy as well, as far as music videos go.

Robert Frank in Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph by Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: Do you have any future projects scheduled with Frank?

Israel: I don’t know. I’m going to visit him this summer, or it might be early fall. So, we’ll see. To be continued. I don’t know if it will be a film, but it might be a little something. I would work with Robert on anything.

Nicole Maturo is an executive assistant at the Aperture Foundation.

Robert Frank–Don’t Blink will be screened beginning July 13, 2016 at Film Forum in New York.