Photography at Novartis AG

In 2002, Daniel Vasella, outgoing chairman of the board of directors of Novartis AG and a director of American Express and PepsiCo., had an innovative notion regarding Novartis’s annual reports. Why not bring to it the same visual acuity and excellence that he had brought to bear on the Novartis campus in Switzerland? And so he reconceived and has created a series of reports drawing on the vision and sensibilities of what has evolved into an extraordinary roster of photographers: Martine Franck (2002); Nikos Economopoulos (2003); Cristina Garcia Rodero (2004); Jean-Baptiste Huynh (2005); Alex Majoli (2006); Giorgia Fiorio (2007); Stuart Franklin (2008); Steve McCurry (2009); James Nachtwey (2010); Eugene Richards (2011); and Mary Ellen Mark (2012). Each has completed a year-long commission. After Mark shared some of her experiences with me in the fall of 2012, I wanted to speak with Dr. Vasella to understand both his passion and his criteria. What follows is our discussion, which took place between November 2012 and January 2013. —Melissa Harris

[Note: click the arrows above to scroll through a slideshow of images.]

Melissa Harris: Does a specific mission or philosophy guide Novartis? Does that relate to your reason for welcoming artists to work with the company?

Daniel Vasella: Yes, our mission is to always find better medicines for patients, and that implies curing and caring for people. Human beings are at the center of all we do. Art is an essential part of human existence, a very important way to express feelings and thoughts which are not always rational or conscious. Artists have ways of crossing barriers and boundaries, transcending cultures. So, art in companies often builds bridges and touches people and associates.

In choosing specific photographers, you always have to look at a person’s background. I myself am trained as a physician and that influences me.

MH: In what particular area?

DV: I was trained in internal medicine and psychosomatic medicine. That has always remained close to my heart.

MH: What role does art and architecture play at Novartis?

DV: I do believe our “internal” Novartis audience responds to the art collection, and also the excellent and diverse architecture that comprises our campus. We have a highly educated employee base. Our concept was to create a lot of open space, to facilitate interaction inside the buildings, but also between buildings—in the courtyards, the open spaces, and so forth. We aim to integrate these spaces with art.

For example, the first building was conceived as collaboration between a painter and an architect. The painter did the outside facade, the design, and the architect completed the rest. In every building, we have one or more artists—but at least one who makes a major intervention.

MH: So part of the philosophy, then, in terms your sensibility, has to do with collaboration at some level.

DV: Yes, collaboration is essential. Nobody can achieve alone what we can realize collaboratively. Our work is such a complex endeavor. How do you get people to work together not only vertically within one function, but also across functions? How do you make sure that people’s intrinsic motivation for the job they are doing is not constrained, but is appreciated and utilized?

Along these lines, the annual report was at one time just an informational and promotional approach to community building, but did not actively engage people. It was my ambition to have the annual report embrace the high standards we apply in other areas of our business. The photography it contained should be more than simply photography; I felt it should go beyond the text. I am much more of a visual person.

MH: But how did you get this way?

DV: If only I knew! For my parents, art was important. Probably more for my mother than for my father. We had very little, but it was always appreciated. I grew up in Switzerland. At seventeen, I began to collect Japanese prints. I did not have a very significant budget but all the money I had went into the prints. I loved it. Maybe my brother played a role also. He is ten years older than I am and liked Asian art.

Then I took art history classes. I remember we visited the medieval town in which I grew up, and for the first time I looked at the houses, the architecture. Because I had been taught to look at specifics, and symbolic meanings, and the Gothic style of building, I became very interested.

MH: When did photography come into play?

DV: At the same time; no, in fact, earlier. I started to take pictures myself, and created my own darkroom. I entered competitions, but then I stopped at eighteen. So I had a period during my adolescence when photography was central. It was all I did.

MH: Whose work were you looking at?

DV: Cartier-Bresson for certain things; Newton for others. At the time, there was also a very fashionable Swedish guy who took these nudes of young girls. He created a bit of a dreamy environment, and he photographed these girls in a very romantic setting. It’s completely passé now, but I remember that well, too.

I wanted mostly to make portraits, for example to go and take pictures of people in the street. I hoped to do a book on the homeless, the faces of homeless, across the world …

So now, years later, with the annual reports, I thought I would really like to create something people would rather keep than throw away. Photography is an emotional form of communication. It’s informative, but it’s also very emotional. We have thousands of examples of that.

Then I began to look at different photographers, and then I began to choose.

MH: Did you do this on your own?

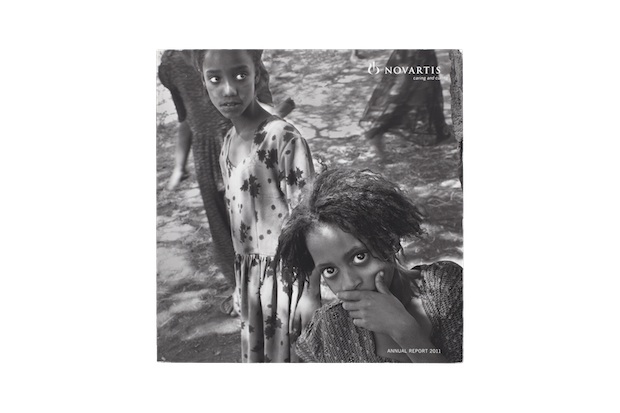

DV: Yes. I went to Magnum, and then to VII to begin looking. As I looked through pictures, I said, “This—I like this.” But I was never looking for the name. Only later did I discover the names, the people behind the photographs. Gene Richards, for example, is very intense, with strong feelings and beliefs. In the end, each photographer speaks with his or her own language. They are all so different, but they are all talking through their pictures. Christina Rodero had some pictures that were almost surrealistic, and Jim Nachtwey moved between showing the cruelty of war to the softness of a man who just loves people.

MH: Well, you picked passionate, mission-driven people with strong sensibilities. But tell me more about your process.

DV: This year we will make a big shift, because I want to do a report in color. I have asked Stephanie Sinclair to be the photographer. In years past I had said, “I really want black-and-white,” because many annual reports with flashy colors and glossy stuff look cheap. Now I believe we have achieved an elegance, and what we do with great photography is clear-cut, so it does not matter.

My process, since the beginning, has been to look at a selection of about twenty photographers each year. I look through their works, books, and materials. I leave everything on my table for a while, and I look again, and I look again. Then I eliminate. I like consistently good work. If I see very good work and then I see something that I think is not as good, I eliminate it.

I am generally left with about three people, and it’s very, very hard to decide. I ask my daughter, who is in her twenties and studied art history and psychology, and my wife to look as well. While I’m listening to their responses, I am also looking again.

MH: Are you looking for storytellers? For individually powerful images?

DV: I think all of the work I’ve responded to has a narrative aspect, although I am not looking for it. But I think that’s the part I react well to.

I’m responding to the quality of the picture, and then I wonder, “Why do they take this picture? Why do they show that?” I think they express something about themselves by how they take a picture. The work says something.

MH: You’ve selected photographers whose work, for the most part, gets under the skin of something, who want to go beyond the surface. They want to ask questions, and they want to go deeper.

DV: What you are saying, “below the surface,” is what I tried to say. “Below the surface” communicates something beyond the cognitive process. It’s more an unconscious understanding of what is being communicated.

MH: What do you tell these photographers? What is the mandate?

DV: I tell them that I would like them to capture patients and caregivers across the globe, and to show the human face. Then we discuss what this might mean; this discussion is different with each photographer.

I try to understand the person also, where we have an overlap, how we can best communicate. As a company we have certain basic needs. For example, we are involved in veterinary medicine, so photographs of animals are part of it. Once I meet the photographers, I trust them.

It doesn’t always work, though. One photographer went to Egypt for us. Unfortunately, he didn’t have a good feeling for cultural limits and boundaries of politeness and was arrested. It would have been a wonderful project, but it didn’t work out.

Another time, we had a problem because we didn’t have all the signed forms. The photographer took a picture of a man with his wife who had an ablation because of breast cancer. She showed it, and that was shocking for people. Some activists asked, “Do you have the release form?” Then, we went searching for the forms …

MH: How much of this has to relate back to Novartis, and how much of it is just about the human condition?

DV: I provide the photographers with the purpose of our business and the aspirations and values we stand for. Equally, they must know our lines of business, our main activities and the outline of the annual report.

I would like to see a representation of the patients and customers we serve. Of course, it is impossible to include all ethnic, age, and social groups, and in addition to that touch on all of our functions. But, at the same time, I leave a lot of leeway. There is so much breadth and possibility.

Once they have completed their yearlong projects, I need to make choices for the actual report. Some may be great pictures, great emotional stories, but for this or that reason I will not use them for the report, which also has to speak directly and clearly to our shareholders. But I may purchase some of these photographs for our collection. Each year, I buy about twenty-five pictures, then I put them on the walls throughout the campus.

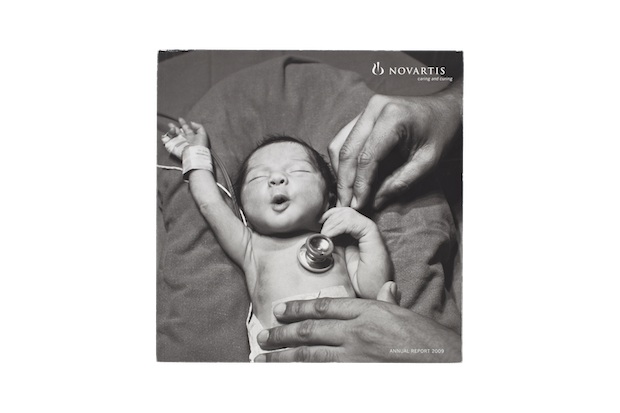

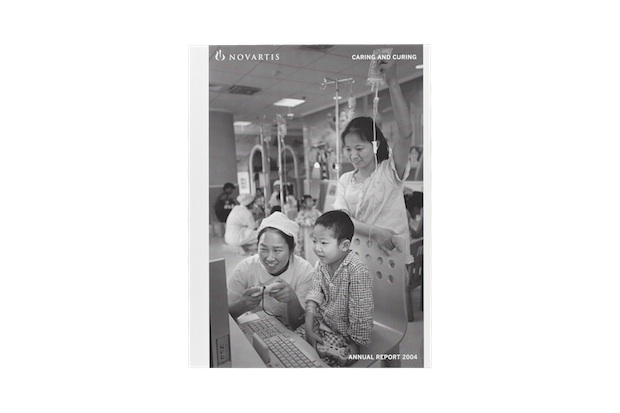

Cover of Novartis AG Annual Report, 2004. Photograph by Cristina Garcia Rodero.

MH: How do you contextualize the photographs? Do you explain the relationship between the images and Novartis?

DV: I have a team who has begun to understand my approach to the annual report, so they prepare options for me. I have put in place a process where I select the photographs, then, according to my assessments, the team tries to place them. Then we look at the report together with the photographer. I like to have the photographer in the room so they can have input. Sometimes we debate the picture selection: “Why don’t you take this one?”

MH: Is that interesting for you?

DV: Yes. They sometimes are connected to what they saw and who they met, and that influences their sense of the picture. I only see what I observe. I may eliminate more of the images, and after I look at the text I say, “That fits the story, that doesn’t fit.”

MH: Is anything taboo?

DV: Yes, anything which would unduly intrude into the lives of a subject, or any photographs without clearance for shooting pictures of the subject.

MH: Do you know yet what Stephanie Sinclair will focus on? What made you select her now?

DV: I am very much looking forward to her work. I saw an initial series of pictures that captured birth, life, and death in and around a clinic in Africa. She also has a specific second motive in mind. It is an idea which I will not disclose other than to say that I was skeptical about it at first. However, based on her enthusiasm, I agreed. Time will tell how well it will fit our project.

MH: Do you believe that photography can (or should?) address and/or comment on the human condition?

DV: The photographers I interact with generally have a keen sense of purpose. They do not want just to shoot outstanding pictures, but also to show what others don’t or can’t see. They aim to touch viewers emotionally, to move them. They have the conscious or unconscious desire to influence and even change attitudes.

MH: Along these lines, do you have any advocacy goals with regard to your annual reports?

DV: I don’t believe I am an activist of any sort. For most of us life has moments of joy, sadness, well-being, and suffering. Unfortunately, many people live under difficult conditions. Novartis aspires to help to reduce suffering from disease and to save lives. So, it is also our intention to show aspects of the human condition.

—