When Women Photographers Went to War

It may seem surprising in 2019 that there is still a need for a gendered exhibition to acknowledge the work of women in the field of war photography. But as the director general of Düsseldorf’s Kunstpalast, Felix Krämer, writes in the forward to this book: “Even though female photographers have been present at the front lines since the First World War [. . .] our understanding of war still has a masculine connotation.”

Women War Photographers: From Lee Miller to Anja Niedringhaus (Kunstpalast and Prestel, 2019) is the companion photobook to the exhibition of the same name that opened at Kunstpalast in March 2019 and will travel to Switzerland’s Fotomuseum Winterthur in February 2020. Showcasing the work of eight photographers, the exhibition was inspired by the museum’s acquisition of seventy-four photographs by the Pulitzer Prize-winning German photographer Anja Niedringhaus, killed on assignment in Afghanistan in 2014. The curators, Anne-Marie Beckmann and Felicity Korn, go a little further than Krämer. They believe that women photographers need special attention because their work is “still quite invisible in the history of not only war photography, but photography in general.”

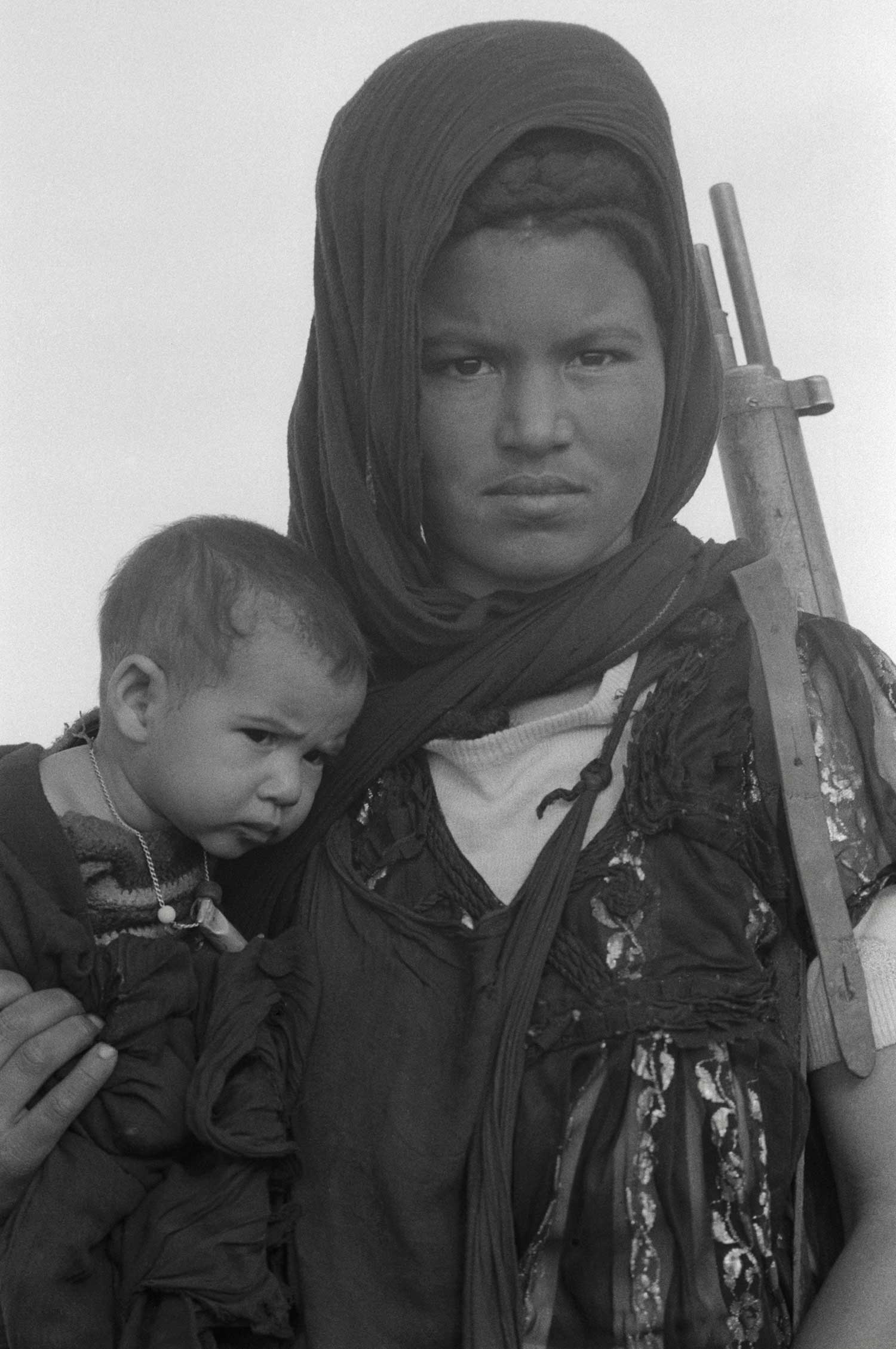

© Françoise Demulder/Roger-Viollet/The Image Works

© picture alliance/AP Images

In a 224-page hardback survey, which includes 163 plates, Beckmann and Korn have succeeded in providing an overview of the work of women photographers covering wars from the Spanish Civil War and World War II, to Vietnam and Nicaragua, to the conflicts that have dogged the Middle East in the past six decades. These photographers include Gerda Taro, Lee Miller, Catherine Leroy, Françoise Demulder, Christine Spengler, Susan Meiselas, Carolyn Cole, and, of course, Anja Niedringhaus.

© Christine Spengler, Paris

The book begins and ends with two photographers who died while covering a war, emphasizing that women are not spared the dangers that beset photographers in areas of conflict. The first of these, Gerda Taro, is regarded as the first woman war photographer. A committed antifascist, she covered the Spanish Civil War, accompanied by her lover and professional partner, Endre Friedmann, whose alias, Robert Capa, they initially shared to sell their photos. Taro died at the age of twenty-six, during the retreat from the Battle at Brunete in 1937, crushed by a tank. Her contribution to the original Capa brand was largely forgotten until the 1990s. The book’s last chapter is dedicated to Anja Niedringhaus, who was shot dead by a policeman while waiting in a car with her Associated Press colleague Kathy Gannon in Afghanistan. She was the only woman on a team of eleven Associated Press photographers who won the Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography in 2005 for their coverage of combat in Iraq.

Women have always played a part in wars, often as victims of the aggression and violence that it brings. They have also joined the ranks of combatants. One of Taro’s iconic photographs of the Spanish Civil War is an evocative black-and-white picture of a woman on one knee, aiming her pistol to shoot. Christine Spengler also photographed women combatants—in Lebanon and the Western Sahara.

It’s telling, however, that it took more than twenty years for the Overseas Press Club of America, which honored Robert Capa with a Gold Medal Award named after him—for the “best published photographic reporting from abroad requiring exceptional courage and enterprise”—to award the prize to a woman. That woman was Catherine Leroy, a French photographer, who won it in 1976 for her coverage of street fighting in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. She was also the first woman photographer to parachute into an area near the Cambodian border with the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team, having covered the Vietnam War from the tender age of twenty-one.

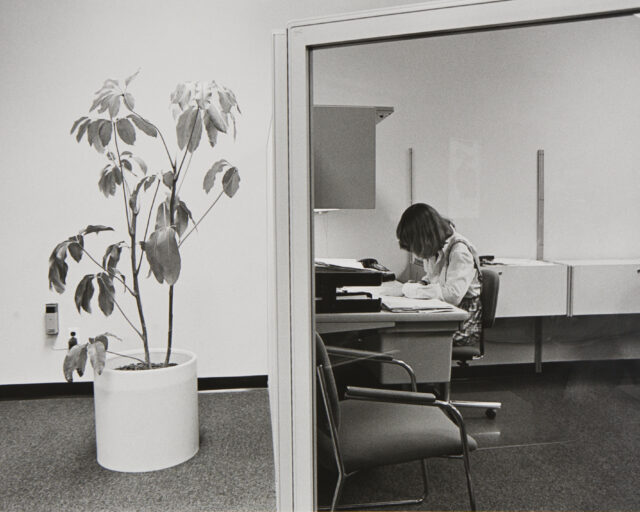

© International Center of Photography, New York

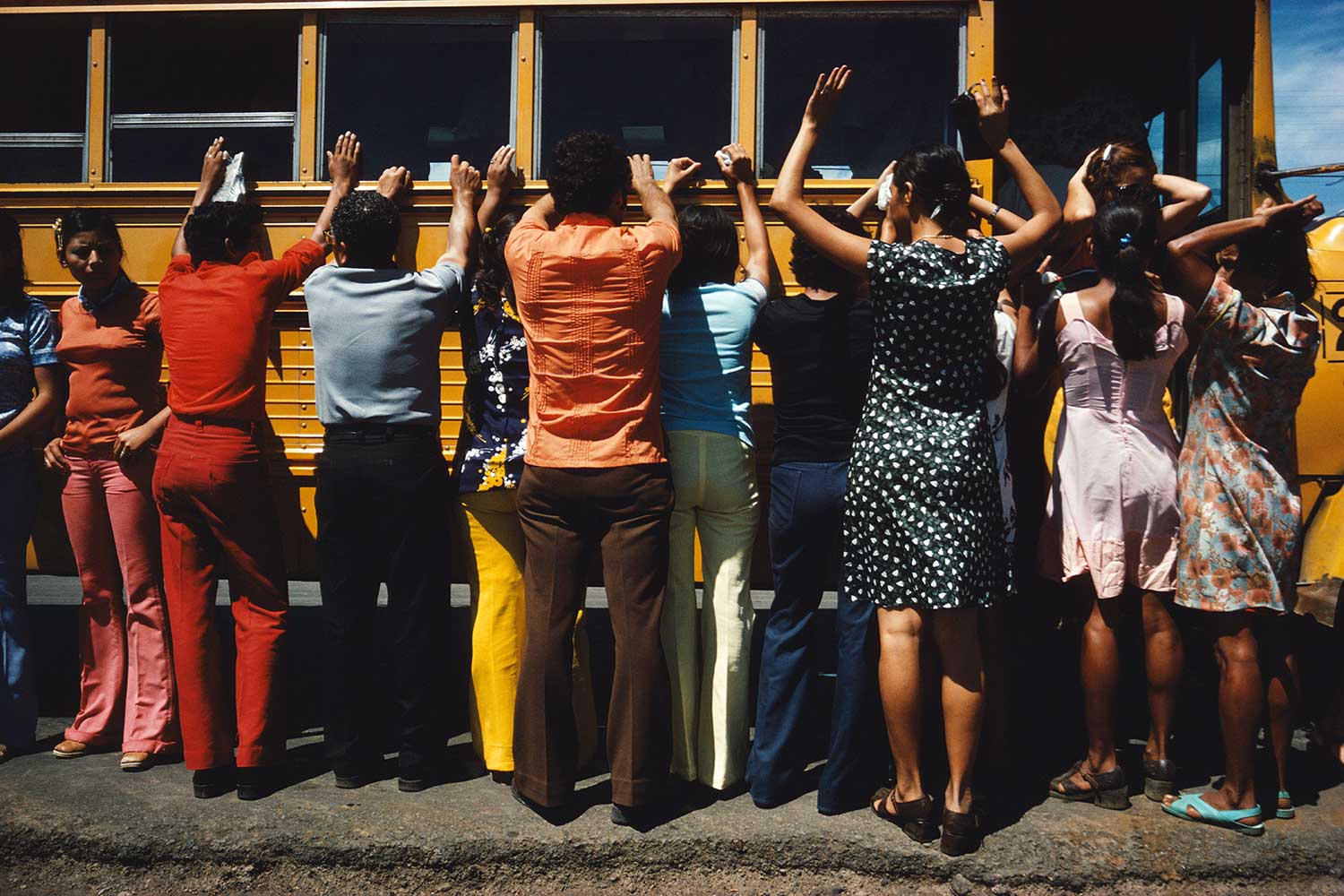

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Korn and Beckmann feel there is no difference between the male and female gaze in photography, but there is certainly a difference in the access that is afforded women. Susan Meiselas, best known for covering Nicaragua and El Salvador, describes the advantages of being a woman in a zone of conflict: “in Central America, I could approach people because they weren’t afraid of women as they were fearful of men. In these highly militarized environments, a woman was perceived as less threatening.”

In patriarchal societies, women photographers can access the female spaces that are guarded from male intrusion. This access inevitably provides women photographers with a different angle, seeing a conflict from the point of view of women and children, an angle that was not always valued. For example, Françoise Demulder’s photograph Massacre at Quarantaine, taken in Beirut in 1976, focuses on the helplessness of a Palestinian woman after a Phalangist attack. Unfortunately, the photograph was archived for eight months by her agency because it “wasn’t commercial enough.” Once published, it went on to win the World Press Photo Foundation’s Photo of the Year prize in 1977, the first time it was awarded to a woman. Patriarchal attitudes exist regardless of the destination. Niedringhaus had to write to her editor every day for six weeks before she was finally sent to cover the war in the Balkans.

© Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times

© Dotation Catherine Leroy

Maybe this book should have been called Eight Women War Photographers, since there are obvious gaps in it. Names like Margaret Bourke-White, Dickie Chapelle, and Lynsey Addario come to mind immediately. The curators explain that they could only show the work of selected photographers in enough depth by limiting their number, but there is room for further books on this subject. In Women War Photographers, we are given a starting point to discover the range of subjects these eight women photographed in their various styles over nearly a century of covering war throughout the world.

As Susan Sontag once said, “There is something predatory in the act of taking a picture.” Yet there is a poetic sense of justice in the increasing number of women who choose to cast a woman’s shadow as witness to war through this predatory act.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review, Issue 017, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.