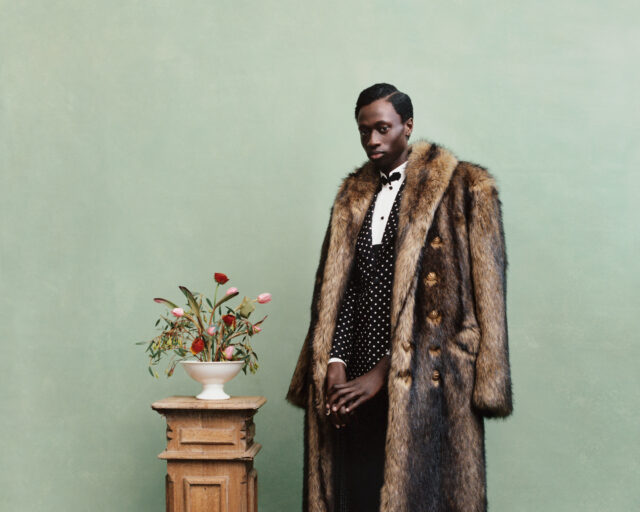

Clifford Prince King, Untitled (Grapes), 2017

What’s remarkable about Clifford Prince King is his ability to make strangers seem both intimate and removed in his work. There is a sense of perceived recognition with his images. Friends of friends you’ve been meaning to meet are within the frames. The faces of under-the-radar creatives whose work you respect but have never told so in person peer back at you. “Oh, I know him,” you hear yourself say to no one in particular as you gaze on the heartbreakingly youthful subjects that make up King’s world. Queer Black men—friends, lovers, some nebulous place in between—lying languidly across bare apartments, cornrowing each other’s hair, holding blunts to one another’s mouths, or staring meditatively away from the camera, naked. The viewer is able to gain what King describes as a “glimpse into a Black gay world through scenes and rituals of the everyday.”

“A lot of the imagery I try to create is just placing Black men in scenarios or scenes that seem familiar,” King says. “And so the ultimate goal to me is creating imagery where we see these Black men—whether they’re masculine-presenting or effeminate—and give that imagery a space.” Pushing back on myopic gender and racial expectations around Black masculinity, King elevates a certain sensitivity and knowingness among queer Black men’s relationships that we rarely see represented.

In Safe Space (2020), King almost melds into a single entity with his two friends as they sit on a bed, entwined between one another’s legs, creating a wordless trust, harmony, and a physical closeness. One’s eye can’t avoid the opened canister of Eco Gel that lies at their feet, ready to lay King’s edges. As a true piece of Black ephemera and the expression of our hair traditions, the gesture represents an intersection of Blackness and queerness that is pivotal to King’s vision.

Slightly out of focus and raw, these photographs document ineffable moments of intimacy. It’s why King’s photo sessions are simply dubbed “hanging out.” Inviting his community over to his home in the West Adams neighborhood of Los Angeles, King prepares dinner or pours a glass of wine, creating an environment of quiet repose before lifting the camera to his eye. His photography becomes about communion and belonging, rather than something forced. “Obviously I want people to feel good about themselves if they’re photographed, but the point isn’t body or beauty, it’s more just about the presence of them being their real selves.” Settings aren’t necessarily pristine. Beds that his subjects curl up on go unmade; jeans that they wear appear stained and distressed; rooms they occupy are unadorned.

You can’t attach a particular historical moment to Run Along Home (2020), an image of mad abandon, one that evokes not only the Southern adage of getting home before the “streetlights turn on,” but also the joy of escaping to one’s home and being alone with a lover. And that is King’s objective. He is focused on creating work that he hopes can be discussed years from now, and in this way, his photography is in conversation with those artists he counts among his inspirations and friends: Deana Lawson, D’Angelo Lovell Williams, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Black contemporary photographers who are putting Black intimacies at the forefront for a lasting effect. King acknowledges that their work is much more intentional than his. But for now, he’s proving the soft power of the everyday.

Read more from Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.