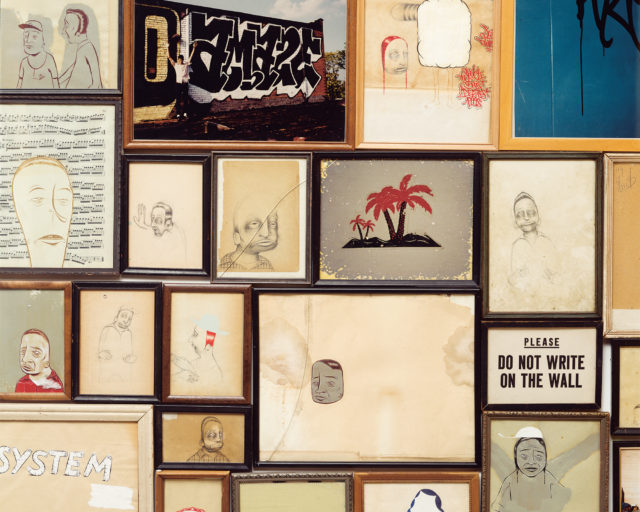

Larry Sultan’s California Home Theater

In the Bay Area photographer’s retrospective, family, home life, and American suburbia take center stage.

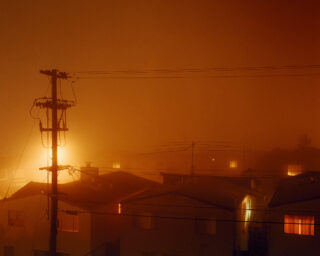

Larry Sultan, Sunset, from the series Pictures from Home, 1989

Location, location, location. The real estate maxim has particular resonance with the work of Larry Sultan, not least because he’s focused on houses and the families who live in them. (His mother, it so happens, was a successful realtor.) But Sultan was also deeply rooted in the aesthetic and conceptual vibes of California—South and North. The former, in the San Fernando Valley, where he grew up, offered the physical and emotional landscape of suburbia, its stucco façades and social dynamics, while the Bay Area, where Sultan’s artistic career thrived, offered guiding photographic and conceptual traditions.

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

The title of Sultan’s retrospective, Here and Home, also has a sense of looking back at a location, the romanticized view of where we came from, from where we are now. And the exhibition has the added value of having opened in 2014 in Los Angeles at Sultan’s hometown museum, LACMA (where the show was held over for months), before traveling this spring to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, in the region where he was such a powerful force as artist and educator, and where he died, too early, in 2009. In San Francisco, his life and work are currently being celebrated with concurrent exhibitions of his solo and collaborative projects, in particular with Mike Mandel, also at SFMOMA, as well as satellite presentations.

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

Back in the 1980s, when I was in my late teens, I followed the same El Camino Real trail up California, so the Sultan lens resonates powerfully in me. His work feels like family. But, due to its proximity to Hollywood, the San Fernando Valley is a very particular kind of suburban location. It’s a terrain that has appeared in TV shows and movies. The midcentury suburban modern house from the Brady Bunch is easy to find—five beds, three baths, 2,477 square feet—on Zillow. People magazine reported last summer that the North Hollywood house, now owned by an elderly woman, was burglarized, but “the interior of the Dilling Street home looks nothing like the house on the show, which was created on a set at Paramount Studios.”

In a 2005 interview, Sultan told me that his work consistently involved “taking the construction of the domestic and looking at it as a theatrical subject.” This is abundantly apparent in the influential series, Pictures from Home (1983–92), starring Sultan’s retirement-age parents. There are clues to lifestyle specifics and location in Dad’s Desk (1987), which looks like a well-dressed set: it’s a still life with coupons, golf balls, a calculator, a handwritten banana daiquiri recipe, and a car registration slip with a Calabasas address. Through these objects, and in various portraits, Sultan’s father emerges with the specificity of a well-drawn fictional character, against which the artist measured himself. Sultan’s mother strikes a mythic, muse-like profile in various pictures; she reclines on a chaise lounge, is subsumed by filmy green curtains, or, in My Mother Posing for Me (1984), she stands wearing white slacks that suggest riding pants in front of a lime green wall. As she looks calmly, directly into her son’s camera, her husband, wearing a busily patterned resort shirt, faces the opposite direction, intently watching a Dodgers game on a color TV. Their poses open endless interpretations of marriage and domestic life.

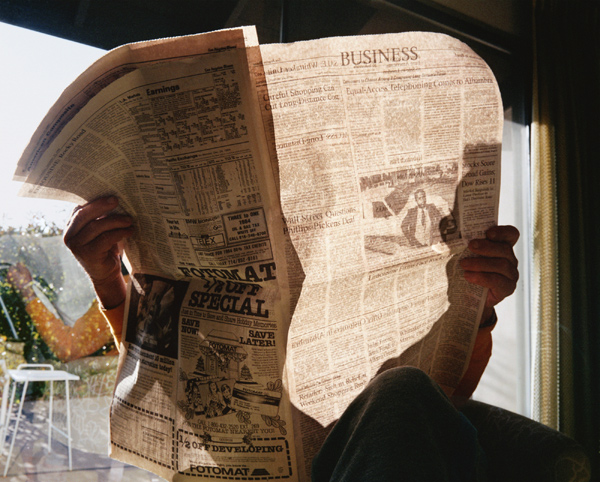

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

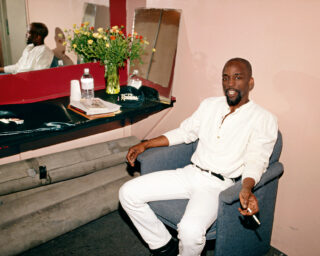

The exhibition and the catalog feature Sultan’s thoughtful, engaging texts. In one, he recalls his childhood home being rented for a commercial, prepped for camera by a full crew. “When they finished lighting the front of our house it was floating in a soft miraculous glow,” he wrote. “It was a dream house. I thought all of the neighbors who were crowded into our driveway were there to watch our house become a movie star.” This dynamic extended and deepened in Sultan’s last two major series, The Valley (1997–2003) and Homeland (2006–9), also traffic in domestic fictions. The Valley is rooted in the common practice of middle-class homes being rented as sets for porn films, a common practice that he first photographed for Maxim magazine. The terrain and appearance of these houses are strikingly similar to the elder Sultans’ residence. That could be their backyard in Cabana (2000), where rose bushes obscure a sexual act at the edge of a kidney-shaped pool. It could be their remodeled interior in Kitchen, Santa Clarita (2001), in which two naked blonde babes sit on a travertine floor and beam at someone off-camera. They’re almost overshadowed by the elaborate but prefab kitchen island accented with decorative jars, a pie on a glass domed cake stand, and an inset gas range. The porn stars are working in well-appointed, middle McMansions; their break times are moments of leisure and make-up sessions, fictions that are also an uncanny reality.

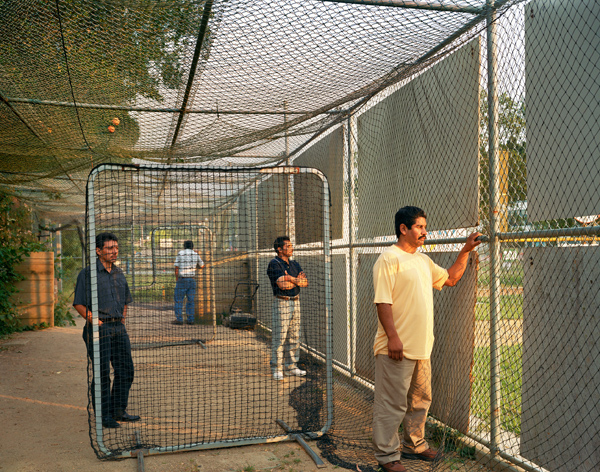

© Estate of Larry Sultan and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

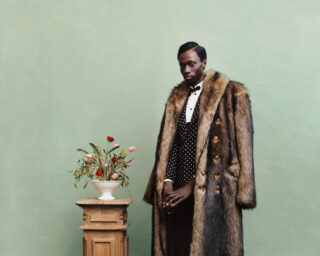

In Homeland, his final body of work, Sultan directed the action more emphatically, creating actual fictions by hiring Latino day laborers to appear in a landscape where they seek work. In a gesture that could have come across as exploitative, Sultan generated a dreamy, wistful tone. “I want to investigate the stereotype of the suburbs and complicate that stereotype, make it a richer field,” he said in a 2008 interview with artist Ben Sloat. And so in Antioch Creek (2008), a man sits on beneath a fantastic riot of cherry blossoms, lost in thought, perhaps daydreaming of somewhere else, while in Canal District, San Rafael (2006), a trio of men walk through a field of dry grass behind a recent row of tract homes, each carrying food, perhaps to a potluck. Both photographs suggests that home is somewhere else, and in the current political climate, they offer a complex, humane view into what’s actually at stake in the immigration debate.

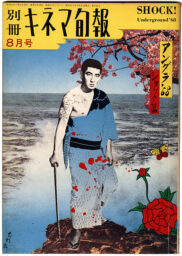

© the artists and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby and Robert Mann Gallery

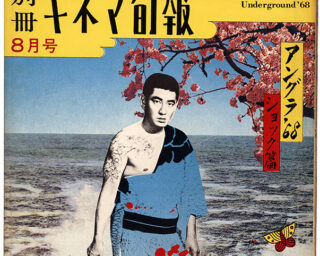

The SFMOMA iteration of Here and Home begins with Sultan’s appropriation works made in collaboration with Mike Mandel, who also grew up in the San Fernando Valley, and whose work from the 1970s will be featured in a concurrent exhibition opening in May. The centerpiece is their groundbreaking appropriation work, Evidence (1975–77), for which they culled found images from corporate and governmental archives. The curious selections reveal a sense of wit and absurdity in awkward moments and striking, probably accidental, compositions. These works also exude a narrative theatricality, of staging within the common workplaces that are extraordinary in their oddness.

© the artists and courtesy Casemore Kirkeby

Mandel and Sultan also collaborated on billboard projects starting in the early 1970s. Perhaps driven by the kind of Southern California reliance on views from the car, they inserted non-sequitur words and pictures, like “Oranges on Fire,” into urban and suburban environments. This series is highlighted in one of a number of satellite exhibitions at Minnesota Street Project. Others include a revival of the Newsroom (1983), in which Sultan and Mandel worked in residence at the Berkeley Art Museum, mining wire service image feeds to categorize official iterations of visual culture, a gesture that seems more complex and relevant in the high speed of current image culture—the new edition features guest editors Dru Donovan, Jason Fulford, and Jim Goldberg—as well as a show of Sultan’s editorial work at Casemore Kirkeby. There are actual celebrities in this mix—Paris Hilton posed in Sultan’s parents’ bedroom in the Valley. “If you put anything in a suburban house … the site functions like an image processor,” Sultan said in 2008. He knew just what to bring home, to place it in that context, and make it indelibly his own—and reverberate far beyond those prefab walls.

Larry Sultan: Here and Home is on view at SFMOMA through July 23, 2017.