Christopher Street Revisited

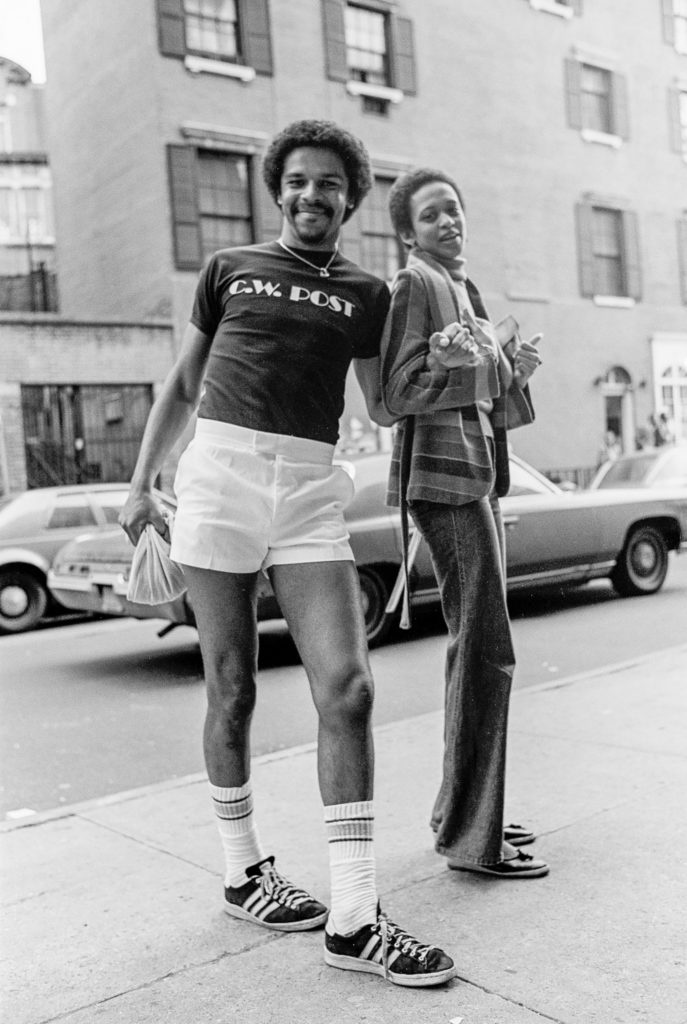

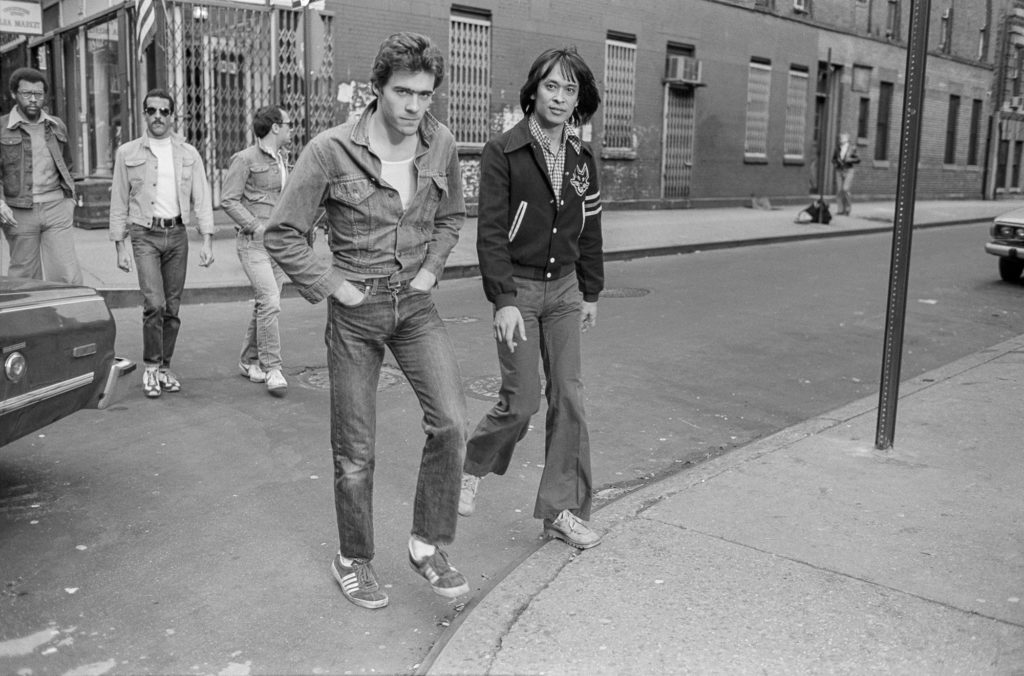

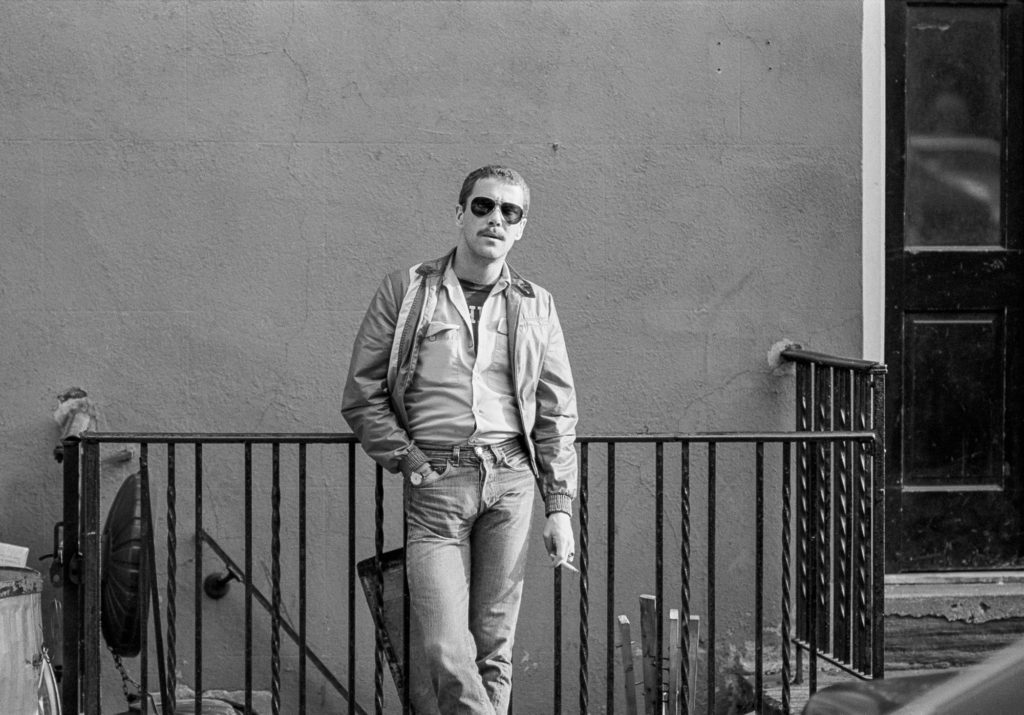

In the 1970s, Sunil Gupta photographed moments of desire and liberation in New York’s gay capital.

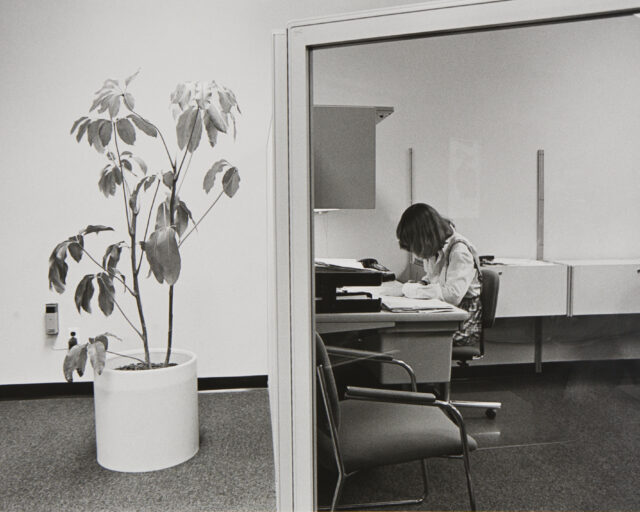

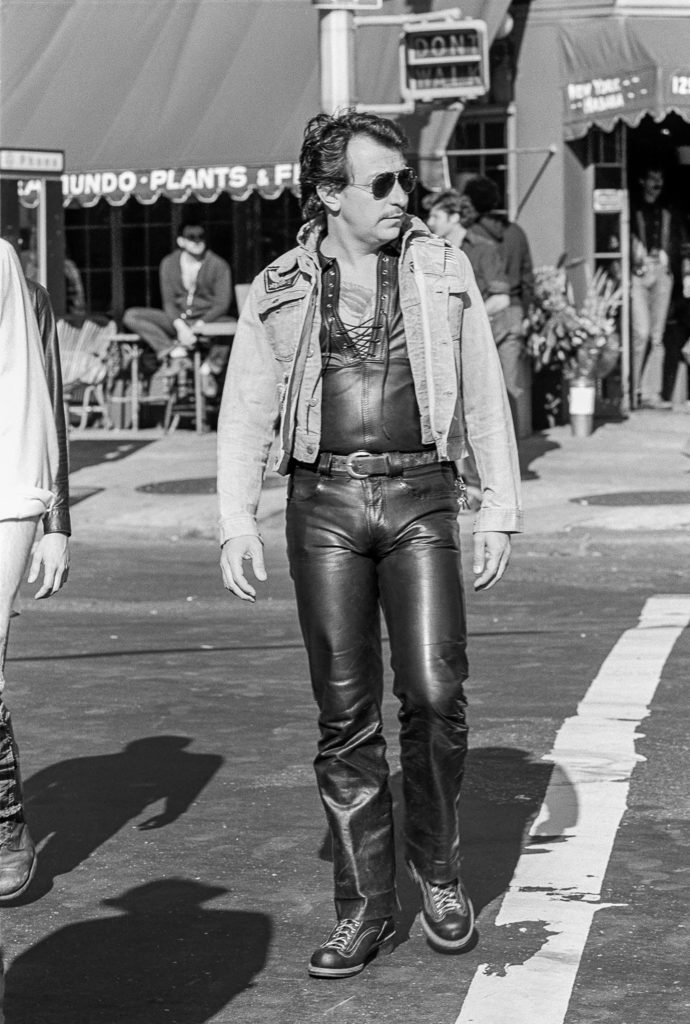

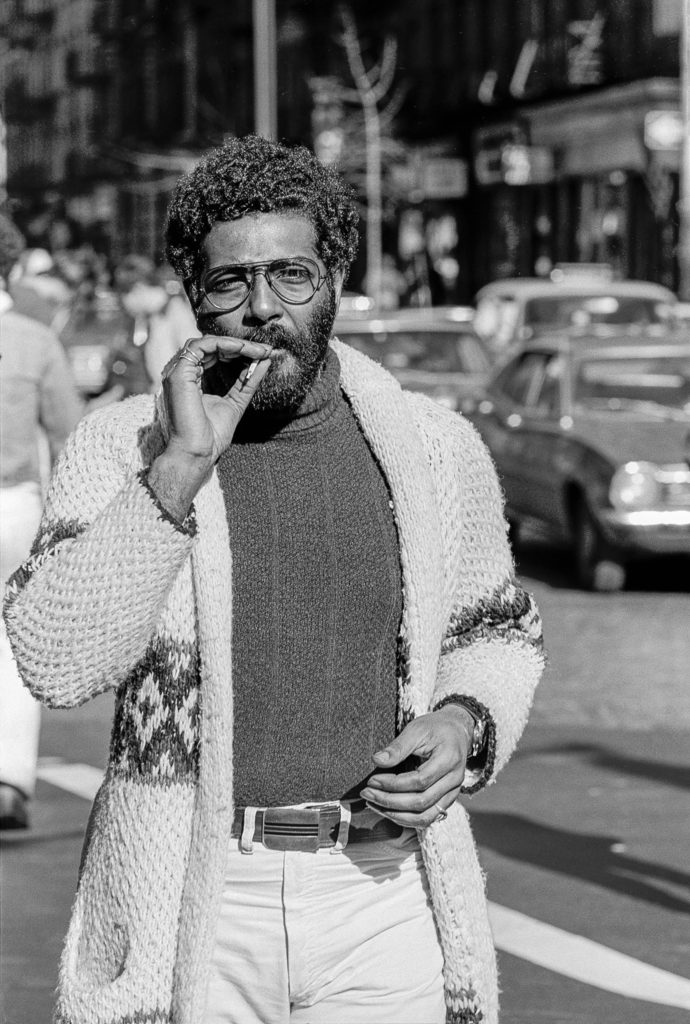

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #22, 1976

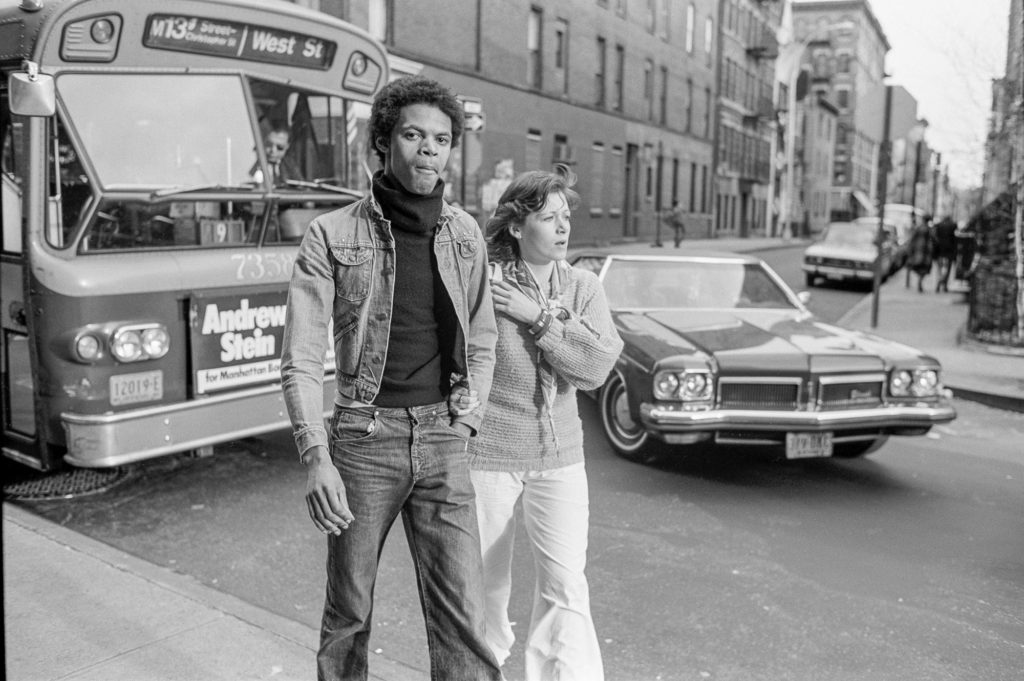

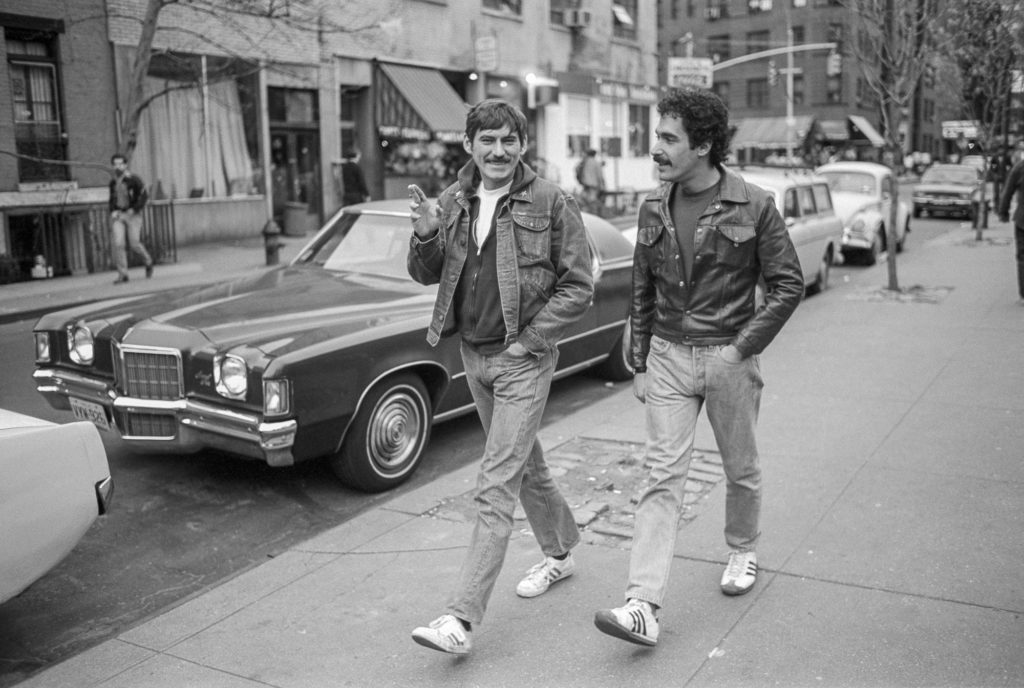

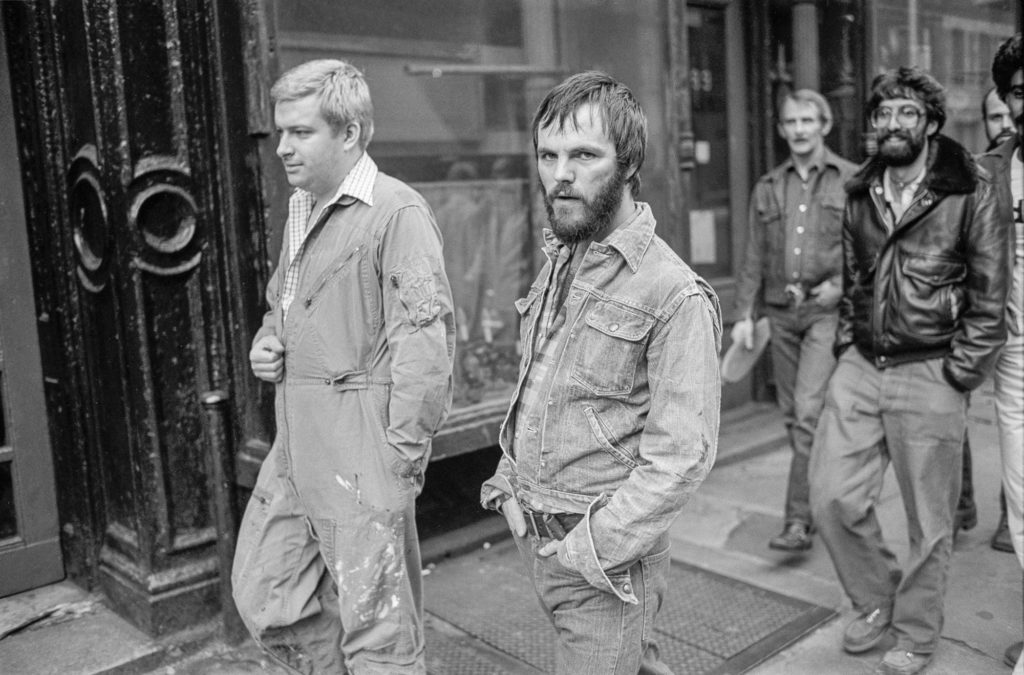

In 1976 and in his early twenties, the New Delhi-born photographer Sunil Gupta left his adopted home of Montreal and came to New York to earn an MBA. The better part of his time, however, was spent conducting business of a very different kind: cruising around the gay mecca of Christopher Street. Camera in hand, and scoping out the men who, like him, had arrived from various elsewheres, Gupta began making pictures of people who wanted to see and be seen, and to see what might happen. Sometimes Gupta’s snapshots were preludes to sex, sometimes instead of it. Other times, the images display other forms of desire, each empathetic and honorable. There’s a curiosity, a need to know in his photographs, which were collected last year in the book Christopher Street 1976 and now presented in a thrilling show at Hales Gallery.

Gupta went on to study under Lisette Model at the New School and take his place among the most accomplished photographers, editors, and curators of his generation, exploring the way identities flower under various sexual, geographical, and historical conditions. But Christopher Street is where it all began. His subjects are engaged in an unprecedented moment in which it seemed possible to build a world of their own. He shows inner lives, barely concealed within the downturned face of a mustachioed man with his hands in his pockets, and outer ones as well, as other men cruise the lens right back, or laugh with each other, unbothered by the stranger with the camera. They were often just engaged in the everyday and extraordinary act of simply existing as gay. In each photograph, Gupta somehow projects a protective and versatile desire: to remember and be remembered at once.

Gupta and I recently walked through his exhibition and then sat for tea, talking about global gay identity, the magic of the darkroom, and cruising as a creative act.

Jesse Dorris: When was the last time these have been shown as a group?

Sunil Gupta: There are about sixty in this that we used for the book. It’s difficult to have exhibitions of all sixty, so in 2015, we tried about twenty-two 8-by-10 prints, which were up at sepiaEYE in New York, and then traveled to Houston.

Dorris: What was it like pulling these out again?

Gupta: I was shooting these at a time when I was just doing it part-time. I was here in New York in business school, and I was just doing street photography. It came out of my gay activism in my undergraduate years and became kind of a serious hobby. It became a natural thing to shoot. I was just on the street corner. Street photography was very fashionable then because of the post-New Documents show with Garry Winogrand and others at the Museum of Modern Art. Then I dropped out of my MBA and began taking photography classes.

Dorris: What was it about photography that called to you?

Gupta: At the very beginning it was kind of a poor man’s cinema. In India, I grew up with Bollywood cinema. It was big and colorful and melodramatic, with sweeping narratives and music. But I was never in a place where I could imagine making anything like that. In Montreal, where my parents moved from Delhi when I was fifteen, I was doing my undergraduate degree, and gay liberation came along in 1970 and we started a student’s union movement around it. I became interested in using the camera and I had a literature-oriented buddy who liked cinema. Basically we made fictional narratives about still frames and tried to make up stories about people like us who were young, single, gay men. Montreal was a much smaller town, and after going to the same bars every weekend for a few months, you’ve kind of seen everyone. So we invented fictional names and backgrounds for people. They had two lives going on: their lives, and what we thought about.

Dorris: You said this was coming out of the liberation movement and that kind of activism. Did you see taking these portraits as a political act? Or was it an act of desire?

Gupta: Most of my photography was initially for public consumption. It wasn’t like snapshots of us. I was photographing gay politics. I went to demonstrations. The campus group Gay McGill was trying to go out into the town and become more relevant to the city. We produced a little paper called Gayzette, so the pictures appeared in that.

Photography came to represent political action and the fiction kind of took a back seat for a while after this. When I was in New York in 1976, I just got drawn into the whole moment of early ’70s documentary stuff that was happening here, in terms of the photography and also the gay scene, both of which suddenly exploded in front of me here. It was quite different than what I had seen in Canada or anywhere else.

Dorris: Tell me what it was like.

Gupta: I lived in London Terrace and all along here was this rough, big scene happening. There were clubs, the Eagle and some other places. In the daytime it was equally busy, just people going by, and obviously I couldn’t have them all, so the next best thing was to photograph them all [laughs]. And fortunately, in this part of Manhattan, the streets all faced the light, so it was great for that.

Dorris: And did people see that were taking the photograph?

Gupta: Yes, they could see me coming, camera pointed, because I was looking through the viewfinder. For me it was like cruising; I was used to going up to people anyways. I used to be quite aggressive in bars, I would just walk up to people. Most people are just waiting to be asked anyway [laughs]. I was impatient.

Dorris: So this is ’76, the height of visibility as a political activity.

Gupta: There was none of this negativity. Sex wasn’t risky; New York City was pretty safe. There was some gay bashing around the fringes, but there was a community response to that so it felt like it could be handled.

Dorris: Why were you taking pictures on the streets rather than at the piers?

Gupta: I think because it gave me photographic structure. It was originally part of a larger idea of street corners in New York. I did this and I also did it further up in the 30’s here in Chelsea. I was very energetic. I just walked up Eighth Avenue up to Thirty-Second or something and the whole world changed, the way New York changes from block to block. I stood on that corner and there were very different people walking by. I thought I would end up with a range of different sights, with different people populating different street corners, but this one became of greater interest to me.

Dorris: It’s really hard to look at these without thinking about the doom that was around the corner. I’ve been thinking about this a lot as everyone is mounting their Stonewall shows and contemporary queer art shows now. I’ve been thinking about if there’s a way of looking at this work without thinking about AIDS and the ’80s.

Gupta: I hope so. It’s meant to be a bit celebratory and not a memorial. I left in ’77 for London and never came back, so I wasn’t here for that terrible time. I thought, in safety, that this was an American disease, we’re never going to get it. The Atlantic is going to save us.

Dorris: How come you never came back?

Gupta: The person I was with moved to England and I was sort of holding on to him. I did regret that I had to leave New York, it felt like a step backward at the time, because London didn’t have this. He promised me it did, but I got there and it wasn’t like this at all. The pubs all closed at 10:30 p.m. And if you held anyone’s hand in a pub, they’d throw you out.

Dorris: Even in Vauxhall or Chelsea or places like that?

Gupta: They didn’t exist. There was only Chelsea. And Earl’s Court was the hub. Britain has this weird history of decriminalizing in ’67-ish and then in the ’70s, the police responded by increasing the number of arrests and entrapments. There was huge police activity against gay men in London in the ’70s. They’d try to catch you out in public places, in parks and toilets. There was a lot more fear and hiding in London.

Dorris: How did the punk scene, fashion, music, et cetera, all affect your work?

Gupta: You know, it made me very aware that I wanted to do something gay. Because in my experience in art school in the ’80s, nobody wanted to do this subject, which made me want to do it even more. I feel really caught in that gay moment, even still. I’m very of that time. People say to me, “Shouldn’t you grow out of this? You’re supposed to mature into something more holistic,” but I still persist in seeing it through my gay identity, my lens. And now we see it all transformed into queer, and now there’s a new problem, that everybody’s queer. And I feel like being gay again. Although, my last book was called Queer [laughs]. That was a mistake, actually; it should have just been Gay.

Dorris: Well now you have your next title!

Gupta: Right, Back to Gay!

Dorris: That would be an amazing reclaiming of a gay identity.

Gupta: I was very invested in identity politics because you know, I was a bit older when I went back to art school, so I was like twenty-four, not twenty, and then for my MFA, by the time I graduated in ’83, I was thirty. The rest were just twenty-three or something. So I was aware of things like Robert Mapplethorpe, which you couldn’t mention in class. When Mapplethorpe happened, Doug and I were like, “We don’t really like this, but we have to go out and support it.”

Dorris: So you didn’t like it, but you supported it anyway?

Gupta: I didn’t have a problem with it. I just felt like it over-dominated. It became “the gay work” and I didn’t think penises were the issue for most of us, certainly not for me or Doug. It wasn’t our sex life that was the problem; there were other problems.

Dorris: You’re taking pictures not at the piers, or the bathhouses, or the parties, but before and after or instead of. They’re clothed on the streets, present in the world, not in the underworld the way Mapplethorpe’s are.

Gupta: There’s been that other battle in the gay subculture, making a place for work that’s not body-centric like that. All of these gay magazines that existed everywhere in the West, their centerfolds all seemed all the same and there was no way to shift it. And you get to this horrible period of very white, hairless models. It was kind of weird.

Dorris: I always thought that was a reaction to AIDS. It was “clean,” “healthy,” no secrets, nothing hiding, everything’s been wiped down. That’s how that world always seemed to me.

Gupta: Yeah, that’s true.

Dorris: I watched a video you made at the Tate where you talk about the darkroom and the magic that happens in there. Could you tell me more about that? What happens in there?

Dorris: In the dark, there’s that final emergence of the image. Being able to control it tonally and all of that, that kind of physics and chemistry is still a bit mysterious and magical. I used to be quite nerdy about darkrooms and chemistry. I had a whole kit of measuring tools. I used to buy raw chemicals, I wouldn’t buy commercial developers, I always mixed them up.

Dorris: Why did you want to do it yourself?

Gupta: Just to have more control with the contrast and things. It’s a lot cheaper also, because chemistry doesn’t cost anything when it’s in a raw state. It’s not complicated, you just have to mix things up. And it was like being a kid, you know, grown-up toys, measuring things, making potions. That was loads more fun and entertaining and you felt better after it. But if I’m sitting for twenty hours in front of a screen, on Photoshop, you just have a backache after it. And it’s so infinite, Photoshop, I find it quite horrible. There’s just no obvious end in sight. In a darkroom there’s a point at which you say, “Okay I’ll fix it now.” In Photoshop you could come back tomorrow and do something else to it. It’s a bloody nightmare.

Dorris: You’re taking sidewalk pictures again?

Gupta: What happened was between 2004 and 2012, I was based in India and I got very involved in reinventing my new gay liberationism and all of this. And as a photography person, I saw that both of these areas needed developing in India when I got there.

Dorris: Were you there when the Supreme Court legalized homosexuality?

Gupta: I was there the first time that it happened. And I joined one of the groups that was involved, which put on shows and festivals and films. I had a photography show. We’d make a call for video and photography and people would rush out and make something locally. The first time we did it, ninety percent of it came from California, and almost nothing from Asia. But a couple years later there was a lot of local stuff. And the curating principle was how to make all the entries look good and put it all up. It was not about choosing the best. So that was great fun. And then we had the first gay pride in New Delhi, so that was fun too.

Dorris: What was that like? Did you photograph it?

Gupta: Yeah, it’s in this other, bigger book. There were rumors spread about possible attacks. When we went to the start of the march, there were maybe about twelve of us who arrived a little bit earlier. We were wondering if there would be any more, really, because of the fear and anxiety of being outed. It was still illegal then. We were a small group of people and a vast army of camera crews and police on-the-ready. So finally, a few hundred people did turn up and nobody was attacked. There’s a new battle to keep it a people’s march. We all have a stake in it, it’s like a big co-op. The consensus so far is that there shall be no branding of anything. No NGOs, no GMHC, and definitely no corporate branding.

Dorris: That’s inconceivable from a Western perspective [laughs].

Gupta: In Bombay they haven’t been able to sustain it, so it’s been corporatized, and therefore bigger. Ours is still littler and a bunch of straggly people walking around. And a bunch of drag queens making a racket. But it’s getting bigger in numbers.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, New York and London

Dorris: Is there a new project on the horizon for you?

Gupta: Yes, I’m trying to attach myself to a Canadian research institute around the forest and migration, which will be the next five years, I anticipate, if I get the funding. I’ve become more into academic research. I just got a PhD.

Dorris: Congratulations! In what?

Gupta: On my own work [laughs], so that was kind of easy. This is a new, third kind of PhD in England. There’s the second one, which was my practice, where you make a body of work and write about it. And now there’s a third one. If you’re an older person like me and if you have at least ten years’ worth of work, you can retroactively write about those ten years, so I picked my last four exhibitions and theorized about them from the vantage point of today. It makes you catch up on the literature about your subject. For example, queer theory has come such a long way in these ten years.

Dorris: So the migration issue is something that’s calling to you?

Gupta: Yeah, my topic was queer migration. I’ve always thought of my experience as a departure from India to Canada and then to New York and England and then I left to India again. But from a contemporary point of view, the more recent idea is to think of it more as an arrival than a departure. In a way, coming to Canada in ’69, a month after Stonewall, I arrived into an identity in a way that wouldn’t have been possible. If I hadn’t left, I would never have been like this. This identity wasn’t happening in India; they missed the whole “gay thing.” They’ve gone from nothing to queer, they didn’t have LGBT. But I really praise my situation in that way, as an arrival.

Sunil Gupta: Christopher Street is on view at Hales Gallery, New York, through June 1, 2019.