How Wing Shya Captured the Mood of Wong Kar-wai’s Films

In the 1990s, Shya worked as a set photographer for the legendary Hong Kong director. A new book peers behind the scenes of Wong’s films—and into the artist’s own life and travels.

Wing Shya, Solace (Session Press, 2024)

Bodies draped sensuously across ornamental, color-drenched interiors; city scenes blurry with speed and streaking with light: for much of his thirty-year career, Wing Shya has crafted such expressionistic images, first forged amid the heady, creative atmosphere of 1990s Hong Kong. Shya, who came to fame as a set photographer for Wong Kar-wai, has since pursued a prolific career across fashion, music, and film, moving nimbly between art and commercial photography, still and moving images. His latest photobook, Solace, surveys his work from 1997 to now. These include behind-the-scenes photographs from Wong’s film sets as well as snapshots from Shya’s own life and travels in Hong Kong, India, and mainland China.

Solace features images that embrace the effects of accidents and mistakes: expired film, light leaks, blurry focus. Similarly, Shya tends to defer agency to people and forces outside himself: the influence of Wong Kar-wai, the demands of the market, curators and publishers, timing. I recently spoke with Shya about his heterogeneous career as a designer, photographer, and filmmaker; the commercialization of Wong Kar-wai’s aesthetic; and the future of photography in Hong Kong. The following interview has been translated from Mandarin Chinese and edited for concision and clarity.

Xueli Wang: I want to start by discussing your new book, Solace. What is the time frame of the photographs in the book? Some look to be from the 1990s while others seem more recent.

Wing Shya: The photographs in the book begin from about 1997 and end from about three years ago.

Wang: Why revisit images from decades ago? What was the impetus behind the book?

Shya: To be honest, I’m not someone who’s very interested in making books. Usually it’s someone else who proposes that I make a book and then I say okay. About four years ago, before the pandemic, I had an exhibition, Happy Together, at Blue Lotus gallery in Shanghai. The curator of that show, Karen Smith, helped me organize that exhibition, and then Shelly Verthime wanted to produce a book of my work, and I said okay. I’m always a bit passive. Usually, I don’t participate in the selection of images either.

For this new book, Miwa Susuda of Session Press wanted to create a book of my work with the designer Geoff Han, so I sent over my photographs for them to select themselves. It’s not that I’m not interested, but rather, I’m open to others’ ideas.

Wang: What about the chronology of the photos and how they’re arranged—did you make those decisions?

Shya: No, nothing. In fact, I’m more interested in the way other people view my work. I want to know how others think, what they like. Sometimes the creative process of a photographer is very lonely—you don’t know how outsiders see your work. So for Geoff to say, “I like this one or that one,” was helpful to me. I sent thousands of photographs.

Wang: The book opens with photographs from India and Hong Kong. Were these taken recently?

Shya: The first photo, taken in India, is from about eight years ago. I had traveled there to visit Buddhist temples and began taking photographs in the morning, as soon as I woke up. The second photograph was taken in Hong Kong, about six to seven years ago, from a mountain peak at dusk in Kowloon. These were taken in my free time, not for work. In terms of chronology, the photographs are all mixed together. I take my camera with me everywhere. When I come across a scene that feels cinematic, I photograph it.

Wang: I’m sure you get this question a lot, but how did you come to collaborate with Wong Kar-wai? And how did your relationship evolve?

Shya: When I came back to Hong Kong after graduating university, I did not have a good sense of the fine arts scene. I got a job as an art director at the company Double X Workshop, which produced music records. My boss at the time was an actor, DJ, and filmmaker, Eric Kot Man-fai. He was starting to make his first film, First Love: Litter on the Breeze, produced by Wong Kar-wai’s new production company, Jet Tone Films. Eric introduced me to Wong as a set photographer because I was the company’s in-house person. But I told Kar-wai: I don’t know much about photography, only simple stuff. Despite that, he asked me to show him a portfolio.

It was a matter of timing. After I finished shooting set photography for Eric’s film, Kar-wai was making a commercial for the Japanese fashion designer Takeo Kikuchi and asked me join for the shoot for two to three days. So I worked as a set photographer for that commercial, but I wasn’t the main set photographer. Wong had also hired a photographer from Japan, while I was the in-house photographer he brought with him from Hong Kong. Afterward, for whatever reason, they chose one of my photographs for the poster. Soon after, Wong was heading to Argentina to shoot his next film Happy Together and he asked my boss if I could go with them for two to three months.

Wang: What was it like working on the set of Happy Together? Did you and Wong have differences in style?

Shya: I was just an insignificant photographer, one among several. I wasn’t on the same level as Wong Kar-wai and also didn’t know much about photography. I went there with my small camera and began shooting with that. On the set, my camera shutter kept clicking and the sound person came and yelled at me. He asked, “Why don’t you have a silencer box to mute the shutter?” I had never heard of such a thing. After that, Wong asked someone to order me one. It had to be tailor made and the wait time was three months. By the time I received it, the film had already finished shooting and we were heading back to Hong Kong.

The whole time I didn’t dare shoot during “action” because of the noise. I couldn’t photograph when the camera was rolling, so I could only photograph behind-the-scenes moments, before and after the actual performance. I would sneak shots of actors on break. I only photographed the “making of” the films, never during the “action,” because I got used to shooting in this way.

Wang: It’s true, many of your photographs from his films actually fall outside the purview of the films themselves. You snuck candid shots of the actors before they were quite ready for the camera. For example, there’s a photograph in the book, a back silhouette of Maggie Cheung smoking alone in a cab. Is this a photograph of Maggie Cheung as herself, rather than her character in In the Mood for Love?

Shya: This is a photograph of Maggie as herself. Her character did not smoke in the film. She also did not ride in the cab alone in the film. Often times, I liked to sneak candid shots. I liked to catch actors when they weren’t ready because they’re in a different state. They’re in a state of rest.

Wang: Did you establish a rapport with the actors you photographed?

Shya: There wasn’t much communication at all. We weren’t in the same class [laughs].

Wang: Did they mind you sneaking shots of them off set?

Shya: They got used to me photographing candids. I once did have some conflict with Leslie Cheung though. In Happy Together, Leslie had a scene at a train station. The director said the station was too loud, so they didn’t record audio. Because of that, I could shoot on set. I shot a lot. But in that scene, Leslie’s character was in a bad mood. He had to conjure that emotional state while I was clicking away nearby and finally he started yelling at me to be quiet.

I approach these photoshoots like a film. I think about the actor, time period, the setting. I think like a director with a script in mind.

Wang: But you must have left an okay impression, since Wong invited you back to photograph on the set of In the Mood for Love and 2046.

Shya: Actually, I never felt fully qualified. But I was happy to be invited to go photograph. I always felt Wong Kar-wai had very high standards.

Wang: Do you feel there’s a stylistic difference between your photography and Wong’s filmmaking?

Shya: I feel I’ve always been emulating his work. I didn’t dare talk to Wong, so I asked Christopher Doyle, Wong’s cinematographer, “How should I take set photographs?” He said, “Watch the monitor. Follow my framing.” I spent a lot of time behind the director, watching his monitor.

Kar-wai had said that it was better for the set photography to share the aesthetic of the film. It’s not really imitation, but following the same framing as the film. But I would sneak shots of other things too. For example, in the book, there are a pair of photographs from In the Mood for Love that are outside the frame of Wong’s film. They capture moments of rest on set.

Wang: Let’s go back to the beginning. You grew up in Hong Kong and studied in Canada for university. Why did you decide to return to Hong Kong after that?

Shya: After graduating from Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Canada, I started a company with some classmates. I majored in graphic design, so our firm specialized in design. We didn’t have many clients, but we had enough. One day, in 1991, I went with some classmates for breakfast in Chinatown and afterward I passed by a newsstand with some magazines from Hong Kong. I began looking through them and thought to myself, “Wow, the design here looks terrible!” Given that I had some fine arts training, I thought it would be a special time for me to be there; it would be something different; I wanted to participate. So I told my classmates, “The state of design in Hong Kong seems terrible, I want to return there to work.” Within a week, I had sold my furniture and my car and was on a flight to Hong Kong.

Wang: Today, we look back at Hong Kong in the 1990s as a kind of golden age of cultural production in film, music, art, fashion. In the years leading up to the 1997 handover, the city hit peak creativity.

Shya: Yes, everyone participated. We didn’t know at the time that it was a peak. I thought it would always be that way. I didn’t understand many things. The market was rich and abundant. There was a strong sense of the future. Even though I was naïve, I think my design sense was at its strongest. I didn’t care about money. I just wanted to work, to create. I think I made my best work back then.

Wang: When did you get seriously into photography?

Shya: After I returned to Hong Kong, in 1991, I was awarded first place in a biennial arts competition. After that, some magazines asked me to photograph for them. Most of them were fine art publications. I would get two to three such assignments a year, not many. The portfolio Wong Kar-wai saw was mostly images from these freelance assignments.

Wang: Did your collaborations with Wong Kar-wai influence how you approached subsequent projects?

Shya: Of course. I returned to Hong Kong in 1991 and began working with Wong Kar-wai in 1996. In the intervening five years, I did mostly fine art photography. Occasionally I photographed for music albums. If they really couldn’t find a photographer, or didn’t have the budget, they’d ask me. Very small assignments. After working with Wong Kar-wai, people from Japan began reaching out to me. One Japanese woman reached out and became my manager. So, around 1997, I began shooting for Japanese magazines.

In Hong Kong, I still spent most of my time working with Wong Kar-wai. I didn’t have much time for anything else. But there were a lot of records being produced in Hong Kong. Every week there were new album releases, so I had many opportunities to do photoshoots of album covers. Because of that, I met many singers.

Wang: Did you see a distinction between commercial and art photography?

Shya: For the album covers, I didn’t always know what they were looking for. At first I approached it like fine art photography. I didn’t understand things like studio lighting. Early on, I’d do it very simply, with just a small camera, then someone told me I needed to use flash and other kind of lights, so I began learning about lighting from photography assistants. From 1997 onward, I became more familiar with the language of commercial photography. I learned as I worked.

Wang: Did working on film sets inform your approach to still photography? Did you create images with a narrative in mind?

Shya: Working on album covers had familiarized me with commercial photography. But when I started working for fashion magazines, my approach changed. In Paris, I met the founder of i-D magazine, Terry Jones. When we met, I showed him a book of stills from Happy Together and he asked me to work on fashion shoots for him, in Hong Kong, in that style. So I began using a film set approach to fashion photography. I worked for i-D for a long time.

Wang: Around 2001, you began making more moving image works—videos and films.

Shya: Yes. In 2001, I began shooting commercials in Singapore. So my collaboration with Wong Kar-wai launched me into different kinds of work. In fact, I don’t feel like I have any single style. When I went back to Hong Kong, in 1991, I didn’t know anything, and since then I’ve just been learning. Even now I’m still learning. I still feel like I don’t fully understand this work.

Wang: In 2010 you made your first movie, Hot Summer Days.

Shya: It came out of my work as a set photographer. While on assignment for a film director friend, I met the project’s scriptwriter, Tony Chan, and we decided to work on a script together. It just so happened that 20th Century Fox was looking to make a Chinese-language film set in Hong Kong. They liked our script and we began shooting right away.

Wang: You’ve worked in Hong Kong as a photographer for over three decades. During this time, Hong Kong has seen enormous changes and upheavals. Have these changes influenced your practice and the way you relate to the city?

Shya: Hong Kong has changed a lot, and I have too. The changes that have come in terms of my own work have to do more with a change in feeling than a change in the city. Back then, there was such a strong sense of the future. It felt like there were endless things to photograph, so much of the future ahead of us. But later, there were fewer music records being released, the market changed, and now the city doesn’t quite have the same sense of vitality.

Wang: Are you working on any new projects now? Has your own style changed?

Shya: Yes, a variety of things. I’m working on some film scripts and directing some commercials. For a while I stopped making commercials because I was too tired. It’s more comfortable for me being a feature film director. As for my own style, many people have described it as cinematic, but I don’t really have a style. I just do what works for me, what I’m used to. The commercials I make, for example, they don’t really have a style. I need to survive. After I opened my studio, I had many employees I needed to take care of. So I took on whatever project I could—I made Pepsi commercials for ten years, for instance. Often I can’t afford to have a style. I must work to earn a living, to support my family. But when I do get the opportunity to do a more artistic shoot, for example for i-D, I tend to approach it cinematically.

Wang: Cinematic in what way?

Shya: I approach these photoshoots like a film. I think about the actor, time period, the setting. I think like a director with a script in mind. Sometimes I’m not shooting actors but models. When I tell them I’ve written out a script or role for them, the model would tell me “I’m not an actor.” But I tell them to follow my lead and just think about the scenario I’m imagining.

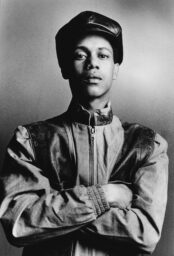

Courtesy the artist

Wang: Is this a common approach for magazine photo shoots? Do you actually write out a script beforehand or think of the scenario on the day of the shoot?

Shya: No, not common at all. I write out a script beforehand. Usually, I first pick the city—for one shoot, I picked Beijing—then I look for the actor and location. To do this, I first look for the right music—this is something I learned from Wong Kar-wai. Before making a film, he would invite me to his room to listen to music. I didn’t understand why at the time, but later it became my routine. The movement of the music matched the movement of the camera. This became my process for photographing too. For example, for the Beijing shoot, it was a rock-and-roll story, so I listened to rock music. I work like this when making films too. After writing the script, I make a playlist that I share with the cinematographer.

Wang: You’re working on the script for a new film now?

Shya: Yes, but I’m also shooting commercials, about two to three a year.

Wang: What’s the film script about?

Shya: It’s set in Tokyo. A story between a mainlander and a Japanese character. I don’t really know much about scriptwriting. In fact, I’m always the passive one—in my commercial work too. I don’t actively seek out new work. People usually come find me. If no one comes then I just stay home, read, and rest. I’m actually quite lazy [laughs].

Wing Shya: Solace was published by Session Press in 2024.