Bryan Stevenson at the office of the Equal Justice Initiative, Montgomery, Alabama, October 2017

Photograph by John Edmonds for Aperture

A visionary legal thinker, Bryan Stevenson has protected the rights of the vulnerable through his work as a death-row lawyer. With the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), an organization he founded in 1994, Stevenson has made strides to end mass incarceration and challenge racial and economic injustice. He has argued cases before the Supreme Court, recently winning a watershed ruling that mandatory life-without-parole sentences for children seventeen and under are unconstitutional. Stevenson’s 2014 memoir, Just Mercy, recounts his experiences navigating an unfair criminal justice system.

But his work extends beyond the legal realm—Stevenson is invested in shifting cultural narratives and making history visible. This is work to which Harvard professor and art historian Sarah Lewis, guest editor of Aperture’s 2016 “Vision & Justice” issue, is uniquely attuned. Lewis has written at length on the urgent role of art in social justice, on the corrective function of images and how they enable us to reimagine ourselves. Last October, Lewis visited Stevenson at his office in Montgomery, Alabama, for an extended conversation. Central to their discussion were Stevenson’s next projects: on April 26, 2018, he will open the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, which will honor the lives of thousands of African Americans lynched in acts of racial terrorism in the United States, and the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, which will trace a historical line between slavery, lynching, segregation, and mass incarceration. Of his work, Stevenson remarks, acts of truth telling have a visual component. “If we just go to the public square and people say some words, it doesn’t have the same power.”

Sarah Lewis: It’s a rare privilege to be able to talk with someone doing work in the realm of justice who understands the role of culture for shifting our narratives regarding racial inequality. I want to have a conversation about how culture, specifically photography, has shifted national narratives on rights and race-based justice in the United States.

Bryan Stevenson: Yes.

Lewis: To begin, I would say that we must consider the journey from 1790 with the Naturalization Act, when citizenship was defined as being white, male, and able to hold property, to the present-day definition of citizenship. The question becomes: Is this journey a legal narrative or is it also a cultural one?

Stevenson: Absolutely.

Lewis: You’ve spent a lot of time dealing with this history as it relates to emancipation and slavery, up until the current day. How did you arrive at a place of seeing the importance of culture for getting people to understand this work?

Stevenson: When I first started going to death row in the 1980s, I was constantly seeing things that communicated really important truths about the experience of the men and women I was meeting in these desperate places. You would see people interact with each other, constantly sharing gestures of compassion and love and support. You’d witness people acting in ways that were so human. And yet they were being condemned, in large part, because there was a judgment about their absence of humanity.

To counter the unforgiving judgment, I wanted other people to see what I saw. And, if anything, it was through the experience of being in jails and prisons, year after year—seeing this rich humanity and the redemption and transformation of individuals, despite the harshness of the environments—that I became persuaded that if other people could see what I see, they would think differently about the issues presented in my work. So, in the 1990s, when we first started representing our work in a modest way, images became an important part. In our first report we used a picture of the Scottsboro Boys. And we also used a picture of a client with compelling features who had been on death row for twenty years. For me, it has always been clear that there is a way in which photography can illuminate what we believe and what we know and what we understand.

It led me to increasingly use imagery to try to help tell the story of our clients. After twenty years of doing that work—and we had a lot of success, but we also saw the limits—I became aware that the rights framework, the insistence on the rule of law was still going to be constrained by the metanarratives that push judges to stop at a certain point: the environment outside the court. That’s what pushed me to think more critically about narrative, not just within a brief, within a case, within an action, but more broadly. And when it comes to narrative struggle, there is nothing that has been more confounding than racial inequality.

Soil from Alabama lynching sites, collected as part of EJI’s Community Remembrance Project, Equal Justice Initiative, Montgomery, Alabama, October 2017

Photograph by John Edmonds for Aperture

Lewis: There’s much work happening in the arts around the nexus of art, justice, and culture. But you’re doing the work of having this become more understood in the wider realm. It’s so crucial. Something that I asked myself as I began this work was: What is the connection between culture and justice? This piece about “narrative” is what unlocks that.

Stevenson: That’s absolutely true for me. Because in many ways, our inattention to narrative is what has sustained the problems we’ve tried to overcome.

Lewis: Yes. Inattention and also unconscious conditioning by it.

Stevenson: Absolutely. So if we think differently about what happened when white settlers came to this country with regard to native populations, if we actually identify what happened to millions of native people as a genocide, the word genocide introduces something into the narrative that is quite disruptive. We’ve been hesitant to use the word genocide, because the narrative would shift in really powerful ways if we understood the violence and exploitation of native people through that lens.

I think the same is true when you look at the African American experience in this country. I’ve gotten to the point where I believe that the North won the Civil War, but the South won the narrative war. They were able to hold on to the ideology of white supremacy and the narrative of racial difference that sustained slavery and shaped social, economic, and political conditions in America. And because the South won the narrative war, it didn’t take very long for them to reassert the same racial hierarchy that stained the soul of this nation during slavery and replicate the violence and racial oppression that existed before the great insurrection.

It’s the narrative of racial difference that condemns African Americans to one hundred years of segregation, exclusion, and terror, following emancipation. Had we paid more attention to the narrative, we would not have seen the U.S. Supreme Court strike down all of those acts by Congress in the 1870s that were designed to protect emancipated black people and create racial equality. But the Supreme Court embraced the narrative that basically maintained that black lives are not worth risking further alienation of the South. It wasn’t about law for the court. The law said that we were all equal, but the narrative allowed the court to accommodate inequality and racial terror.

Narrative struggle is where we have to pay attention if we want to avoid replicating these dynamics as we continue to face the same problem of racial divide.

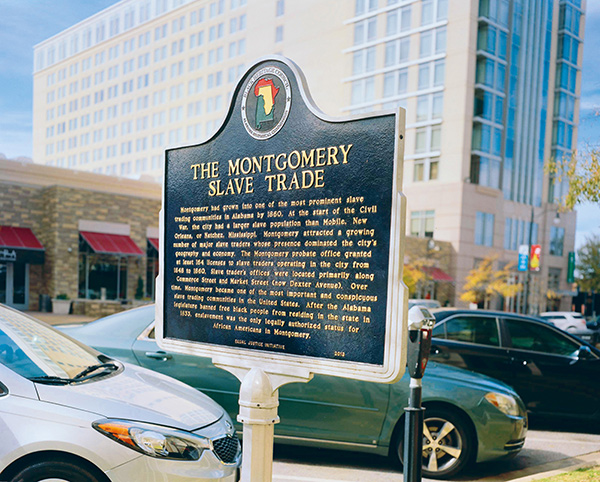

Memorial plaque to the Montgomery slave trade, placed by the Equal Justice Initiative, October 2017

Photograph by John Edmonds for Aperture

Lewis: On this point about looking at the ways in which whiteness became conflated with nation through narrative, there are a number of things to mention. But just to get back to the Native American piece and the criminalization of rights-based action, it was, in large part, photography that legitimated acts of genocide. Edward Curtis’s photographs, for example, naturalized and supported the genocide.

Stevenson: That’s right. Because if you can create the idea that these native people are savages and you can create a visual record that supports that idea, then people don’t view the abuse and victimization as they ought to.

What’s interesting to me about some of that early art and visual work is that it’s really about perpetuating the politics of fear and anger. And fear and anger are the essential ingredients of oppression. Art is complicit in creating these narratives that then allow our policymakers to perpetrate acts of injustice, decade after decade, generation after generation.

Lewis: Absolutely. But before we get more to the current day, I think there is a framework here that we should acknowledge, and a thinker who did the courageous work at the time, during the Civil War, to put out this idea about narrative—and that is Frederick Douglass. He gave a speech during the Civil War that he called “Pictures and Progress.” He confused his audience at the time by speaking about what seemed like a trifle during this nation-severing conflict. Something seemingly as small as a picture, he argued, could have as much force as a political action, as a law. It’s a fascinating speech. He was interested in what he called “thought pictures.” This was his gesture toward narrative; he used this term to describe the ways in which culture, what we consume daily through pictures, can shift our notion of the world. That is what he thought would effect the change. Douglass was the most photographed American man in the nineteenth century, for good reason. He believed in this idea.

Stevenson: It’s a really powerful insight, that he could appreciate how getting people to see his humanness was critical for them to understand the inhumanity and degradation of slavery. In many ways, Dr. King had that same insight.

Lewis: Yes.

Stevenson: He understood that the spectacle of nonviolent resistance to white, armed, military repression could create a consciousness about the African American struggle in the South that could not be created any other way.

As we’ve been working on our Legacy Museum, which explores slavery and the human suffering created by the domestic slave trade, it’s been frustrating, because there is so little photography or imagery that exposes the inhumanity of enslavement. It’s almost as if there was a real effort to avoid visual documentation that might have implicated us and revealed our complicity in facilitating such great suffering.

I have found in the published narratives of enslaved people this unbelievably rich source of content, not visual in the sense of photography or art, but visual in terms of language. They tell stories. They use the narrative form to create a very intimate picture of what it was like on the day when their children were taken away on the auction block, or when they lost their loved ones. In our museum, we’re using technology and video to give animation to these words through performance. I’m really excited about it because it creates a kind of intimacy, it paints the kind of picture that Douglass tried to achieve.

Charles Moore, Martin Luther King, Jr. is arrested for loitering outside a courtroom where his friend Ralph Albernathy is appearing for trial, Montgomery, Alabama, 1958

Courtesy Charles Moore Estate and Steven Kasher Gallery

Lewis: We’re sitting here in a building in Montgomery that functions as a kind of narrative correction. Is that right?

Stevenson: Yes. We’re a few blocks from Dr. King’s church and from where Rosa Parks started the modern civil rights movement. However, what we didn’t appreciate until we began our racial justice project is that we were also in the epicenter of the domestic slave trade. That part of the historical narrative of this community had largely been ignored. But it became clearer to us that this street, Commerce Street, was one of the most active slave-trading spaces in America. Tens of thousands of enslaved people were brought here.

Lewis: Hence the name.

Stevenson: Yes, that’s right, hence the name. Thousands of black people were trafficked here by rail and by boat. Montgomery had the only continuous rail line to the Upper South in the 1850s.

So this knowledge made me reimagine how this space could contribute to a more honest American identity. And the marker project was the first thing we did locally, to try to create awareness of this past. If you come to Montgomery, there are fifty-nine markers and monuments to the Confederacy in this city. They are everywhere. “The First White House of the Confederacy” is the sign you pass when you drive into town. Our two largest high schools are Robert E. Lee High and Jefferson Davis High. But not a word about slavery. So putting up these markers that introduced facts about the Montgomery slave trade and the domestic slave trade and the slave warehouses and the slave depots that shaped this city, which were avoided by local historians, was really important.

Lewis: You talked about the need to shift our cultural infrastructure in the United States because of the deliberate silence about racial terror, and, of course, this connects to mass incarceration. But can you talk about the shifts that you’re hoping will occur in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the museum in Montgomery?

Stevenson: I do think we have to make our history of racial inequality visible. We have been so inundated with these narratives of American greatness and how wonderful things have been in this country that it’s going to take cultural work that disrupts the narrative in a visual way to force a more honest accounting of our past. People take great pride in the Confederacy because they actually don’t associate it with the abuse and victimization of millions of enslaved black people. So that has to be disrupted.

What appeals to me about the markers is that they are public; everyone encounters them. We can create a museum. We can create indoor spaces that try to express and deal with these issues. But a lot of the people who need this education are never going to step inside those places. Public markers, however, can’t be ignored, and we have continued that effort with our work on lynching. Our goal is to mark as many of the lynching sites in America as possible. We use the words racial terrorism on each one of the markers. We name the victims. We give a narrative that contextualizes the brutality and torture black people endured. I do think that’s important, to challenge the public landscape, which has been complicit in sustaining these narratives of white supremacy and racial inequality. That’s another way in which acts of truth telling have a visual component. If we just go to the public square and people say some words, it doesn’t have the same power as permanent symbols of collective memory.

We are opening the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, which will acknowledge over four thousand victims of lynchings and identify over eight hundred counties in America where racial terrorism took place. Hundreds of six-foot monuments will be on the site, including sculptures created by artists who contextualize lynching within an understanding of slavery, segregation, and contemporary police violence. Deeper exploration of these issues is then possible in the museum, and all of this, for me, is really exciting. Particularly in these political times where you’ve seen the retreat and obfuscation of historical truth. It was a shock to me in 2008 how quick people were to assert that we now live in a postracial society; that was obviously incredibly naive.

Photographer unknown, An airman pauses to examine the “Colored Waiting Room” sign at

Atlanta’s Terminal Station, January 1956

© Bettmann/Getty Images

Lewis: It occurs to me, and I wonder if this is correct, that you focused on your own experience of needing narrative to communicate what you were seeing with your clients—how racial terror and lynching have structured the criminal justice system and the landscape of racial inequality.

Stevenson: Yes, absolutely. It’s not a surprise that after emancipation, people went from being called “slaves” to being called “criminals.” Convict leasing and lynching were about criminalizing black people. Rosa Parks makes her stand, and she’s immediately criminalized. Those women who fought for equality on buses here in Montgomery, what they were being threatened with was a formal designation as criminals: Claudette Colvin, Mary Louise Smith, all of these women.

The notion that resistance to racial inequality makes you a dangerous criminal has always been there. So, then, it’s not a surprise that after the success of the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act, prosecutors begin focusing on “voter fraud” in the black community, followed by this new War on Drugs, which then leads to the United States having the largest incarcerated population in the world. The rate of incarceration is just unprecedented.

I think that the criminalization of black people, and now brown people who are deemed illegal because of their state of national origin, is very much a part of the American story, and it’s been present with us in ways that we just haven’t acknowledged. We criminalized Japanese Americans during World War II and put them in concentration camps, but were unconcerned about Italian Americans and German Americans.

Lewis: One of the interventions of the civil rights movement, it seems, is to reframe criminality and rights-based behavior as actually a positive, an act of citizenship.

Stevenson: Right.

Lewis: Or as an indicator of such. The 1958 image that Charles Moore took of Dr. King is probably iconic in that regard.

Stevenson: Right. We used that for one of our calendars. I think the images we often see of Dr. King are with him poised, speaking in front of thousands of people in these esteemed spaces, where his leadership is what’s being highlighted. What’s powerful to me about this image is that here he is being criminalized. He’s being brutalized by law enforcement. And there is some fear in his eyes, because there is the uncertainty of what will happen. Because the long history of black struggle is that once you are put in this criminal status your survival is not guaranteed, your safety is certainly not guaranteed. And yet, he persists, and he continues. I love the way Coretta Scott King is witnessing his abuse with such dignity and confidence. It just says a lot about the kind of courage that is needed to fight a fight like this.

Rosa Parks is also so powerful in that regard. One of the first people we want to honor in our memorial garden is Thomas Edward Brooks, a black World War II veteran who shaped Rosa Parks’s activism on the buses.

In 1950, Mr. Brooks returned home to Montgomery, in his uniform. The segregation protocol on the bus was, of course, that you get on at the front of the bus, you put your dime in, then you get off the bus, and you walk to the back door, and get back on, and head to the back. Mr. Brooks gets on, puts his dime in, but he doesn’t get off the bus. He walks down the center aisle to the back. The bus driver is screaming at him and calls the police. The police officer comes on the bus, and Mr. Brooks is in his military uniform in a defiant posture, according to witnesses. The police officer just goes up and hits him in the head with the club, knocks him down, rattles him, and he starts dragging him toward the front of the bus, and when he gets to the front of the bus, the black soldier gathers himself and jumps up and shoves the police officer and starts running, and the officer takes out his gun and shoots him in the back, and kills him.

Two years later, the same thing happens to another black soldier. Rosa Parks was the person who was documenting these tragedies, as a secretary to the NAACP. And that sense of violent repression and menace—the understanding that police officers could kill a black soldier, shoot him in the back—took her commitment to change conditions to a whole other level. It was no longer just insult and subordination. It was lethal, which makes her protest all the more inspiring.

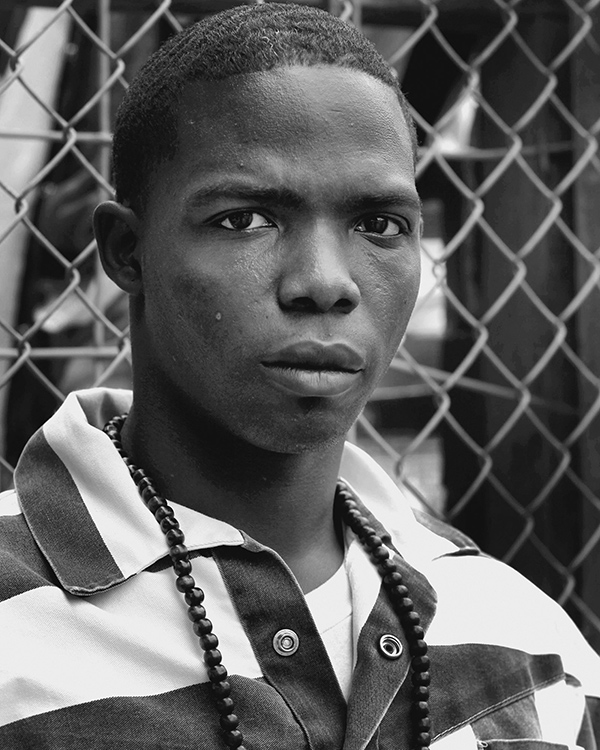

Chandra McCormick, Young Man, Angola Prison, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Lewis: Your work allows us to understand the narrative of black veterans and the way they were targeted and subjugated to racial terror. It’s a feature of the landscape that we need to understand.

Stevenson: Well, it’s an important part of the story, because, you know, W. E. B. Du Bois and others said, We go fight for this country; let’s save this country, and then they will save us. And it didn’t happen after World War I. In fact, it was the opposite. They were targeted and victimized for their military service. It complicated the idea of black inferiority to have black soldiers go to Paris, France, and be triumphant and successful. That’s why, in some ways, the lynchings increase during this time, in 1919, 1920, 1921, when black soldiers are returning home and creating a new identity. The same thing happens after World War II; you see this increased racial violence in the 1940s targeting black veterans.

My dad just passed away. He was born in 1929, and he fought in the Korean War. He was very active in the church, and he talked about his faith all the time, but he never talked about his military service. For economic reasons he wanted to be buried at the veterans cemetery, and there you see all of these U.S. flags, and there’s all of that symbolism of nationalism and American pride. When I got to his grave site, they put on the little plate, “Howard C. Stevenson, Corporal, U.S. Army, Korean War,” and a flag. But it wasn’t completely true. He served in a racially segregated unit and was denied most of the rewards white veterans received for their military service; his rank and service were diminished by racial bigotry. And there is no acknowledgment of that. I believe his willingness to serve despite racism should be recognized. For me, this highlights how much work we still need to do in this country around truth telling. I believe that truth and reconciliation are sequential. You have to tell the truth first. You have to create a consciousness around the truth before you can have any hopes of reconciliation. And reconciliation may not come, but truth must come. That’s the condition.

Lewis: If someone were to say that we’re having a conversation about culture and mass incarceration or racial inequality, they might think that it’s about the portrayal of that specific group that has been terrorized or dehumanized by these actions. But, in fact, it’s also about the opposite, the way in which the presence of racial terror has also conditioned the entire population.

Stevenson: Absolutely. That point is so critical. Terrorism, the violence of lynching, is critical for understanding how you could have decades of Jim Crow. No one would have accepted drinking out of the inferior water fountain or going into the less desirable “colored” bathroom unless violence could be exercised against you for noncompliance with segregation with impunity.

Racial-terror lynching propelled the massive displacement of black people in the twentieth century. The idea that black people went to Cleveland and Chicago and Detroit and LA and Oakland as immigrants, looking for economic opportunities, is really misguided. You have to understand that they went there as refugees and exiles from terror and lynching.

Today we have generational poverty and distress in urban communities in the North and West, and black people are criticized for not solving these problems, and most people don’t understand how the legacy of racial terror shaped the structural problems we continue to face. That’s what provokes me when people come up to me and they talk about problems in the black family. I’m thinking children and their husbands and their parents by white slave owners, and the commerce of slavery. During the lynching era, black women had to send away spouses and children who were threatened with mob violence for something trivial. We haven’t addressed the devastation and trauma to black family life created by this history.

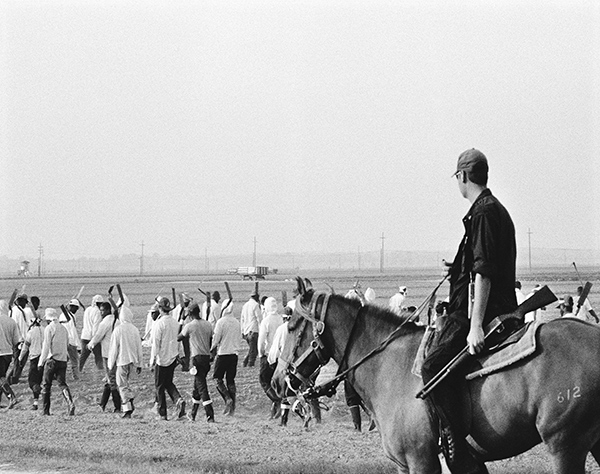

Chandra McCormick, Line Boss, Angola Prison, 2004

Courtesy the artist

Lewis: I’m looking at the EJI report “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.” The photographs demonstrate that watching a lynching was a family activity for some white Americans.

Stevenson: That’s exactly right. And this effort to acculturate white people to accept and embrace the torture, brutalization, and violence they see black people around them experience … it’s a tragic infection that afflicts our society. Nelson Mandela says, in effect, “No one is born hating someone else; you have to be taught.” The way in which we have taught racial violence and white supremacy is intricate, and devastating. It won’t go away without treatment.

Lewis: Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun’s work Slavery: The Prison Industrial Complex, begun in the early 1980s and ongoing to this day, shows the continuation of this violence through photographs of life at Angola, the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Stevenson: We represent lots of people who are at Angola now. Angola has one of the largest populations of children sentenced to life imprisonment without parole in the country. We have clients who received write-ups for not picking cotton fast enough in the 1980s when prisoners were forced to toil in the fields. Now these men are parole-eligible, and we have to explain to the parole board why refusing to pick cotton thirty years ago is not something they should hold against this person when they were sentenced to die in prison. You still have officers on horseback down there, riding around. You still see men going out into the fields. It is a former plantation.

So I think images are really important. The narrative of putting imprisoned, largely black people out in the fields to hoe and pick cotton, which you would think would be just unconscionable to a society trying to recover from slavery, is actually exciting to a lot of people. It’s like the chain gangs they brought back to Alabama twenty years ago. Some people loved the visual of mostly black men in striped uniforms chained together along the roadside and being forced to work. The optics are so important, and it sort of reminds me of those images around lynching. It’s the same thing: Let’s use this imagery to excite the masses so that we can recover something that has been lost, restore something that has been taken from us, and allow us to reclaim an identity that replicates the good old days of racial hierarchy in precisely the same ways. It’s why the phrase “Make America Great Again” is provocative to many of us, and why our indifference to mass incarceration is so unacceptable. I’m persuaded we are still in a struggle for basic equality and there is much work still to be done.

Sarah Lewis is Assistant Professor of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies at Harvard University and the author of The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure, and the Search for Mastery (2015).

To continue reading, buy Aperture, Issue 230 “Prison Nation,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.