Zoe Crosher: Stage Manager

The Los Angeles–based photographer Zoe Crosher has had quite a big year. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art featured her work in a show called Figure and Form after purchasing it for the museum collection; she had her first solo show at Perry Rubenstein Gallery in Los Angeles; and she is included in New Photography 2012 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In each of the exhibitions, Crosher has worked with, intervened in, and re-presented the self-portraits of one woman, Michelle duBois. It’s an archive comprised of over one thousand images of the same woman over the course of her life. In appropriating it, Crosher has tapped into the most American kind of fantasy, at once tragic and aspirational, fictional and sincere, and, above all, reliant on its own photographic documentation. Aperture’s relationship with Crosher predates these exhibitions; in 2011 and 2012, she worked with the organization to complete a four-volume, print-on-demand, limited-edition artist’s book using the duBois archive. I spoke with Crosher in late October.

Carmen Winant: This has been a very busy year for you, participating in exhibitions at LACMA and MoMA and presenting a solo show at Perry Rubenstein. Also, last year you won the Art Here and Now award, and the California Community Foundation Fellowship for Visual Arts. My first question to you is a practical one. How do you manage your time?

Zoe Crosher: Well, it helps to know that it is a finite period. One of the great things about being able to work with a fantastic gallery is the infrastructure. I have an incredible team, and a lot of my job at this point has become efficient delegation. I have a main assistant, plus the archivist and registrar at the gallery, along with three separate production teams. I had wanted to work this way for a while—I knew I would have to in order to realize specific, long-standing ideas—but didn’t quite have the support. Perry [Rubenstein] gave me the opportunity to work within a much larger production model, and that has been essential.

CW: How does being a manager suit you?

ZC: It’s one thing I like about being an artist; you can wear a lot of different hats at different moments. Of course, I am totally obsessed with every detail, the quality of every part of the production.

CW: And you are quite pregnant. I can only imagine that adds to the workload.

ZC: Right, I am going to retreat for a few months when the baby is born. I will start working on a new body of work after that break, so in some ways the timing has been ideal. But when it first happened, I looked at my calendar and thought, How the hell am I going to do this? I had pretty difficult morning sickness, so my functional hours diminished during the day.

To tell you the truth, I didn’t inform anyone for a very long time that I was pregnant because of the professional stigma. People can be very dismissive. I also didn’t think it that it was anybody’s business. When I was at the Dallas Contemporary, the work got a write up in Artforum’s “Scene & Herd” section, which was great. But I was described as a “pregnant Los Angeles artist.” I was shocked!

CW: You worked with the duBois archive for the above-mentioned shows in Los Angeles and New York this year. How much overlap—conceptually or materially—was there between the three? Was that something that you were trying to indulge or resist?

ZC: The duBois project is all about curation, and that shifts intentionally from show to show. The Aperture books really represent this quality of continually re-telling, of the re-writing of the fantasy archive, so maybe we could start there. The first book is titled The Reconsidered Archive of Michelle duBois, and it is full of what I call “Auto-portraits”—images that she planned, executed, and kept—along with all of her “companions.” The second book is about the physicality of the archive, looking at the backs of the photographs, the antiquated language of Kodak film and the front of the albums. The third book is The Unveiling of Michelle duBois. It concentrates largely on her collection Japanese objects, like kimonos, umbrellas, and dolls. She had over one hundred and fifty Japanese dolls! She also travelled to Asia and made a lot of tourist photographs, “collecting,” on some macro-level, the sites as she went. The fourth book, The Disappearance of Michelle duBois, concentrates on the physical disintegration of the archive, the final manipulation of the images into objects. A lot of works from that final grouping are in the MoMA show, and they play with a certain denial of visibility—images of duBois with her head turned away. Beyond that, I crumple and re-photograph the image with a flash, further imposing a sense of distance upon the images. The metaphor stands as an escape from a singular, conclusive, totalizing effort.

The whole project is about the relationship of fiction and the archive, and the impossibility of knowing oneself even after the accumulation of thousands of images. Simultaneously, the arc is about the end—and breaking down—of analog photo technologies.

CW: Can you talk a little bit about these “wall” installations you’ve been creating? The work, which is hung in strategic clusters, often reads as one collective body.

ZC: I’ve worked this way in both the LACMA and MoMA shows, and in both cases it’s been very specific to the institutional wall. Those I’ll call the Disbanding of Michelle duBois. Both of the projects were focused mostly on The Disappearance of Michelle duBois. I was interested in her gaze darting back and forth, as well as the physical inability to see her. So, I come up with various versions, and then create them site-specifically for institutions.

LACMA bought the piece after I won the Art Here and Now award in 2011, and I didn’t ever imagine that they would show the whole thing. I wanted to make a flexible exhibit, so that one could mix and match it based on the surrounding works. The wall was really specific to the space, and the decisions made about the way that the work was hung happened during the installation, through conversations with the curators. Wolfgang Tillmans is in that LACMA show as well, on an opposite wall, and it occurred to me that we have an opposite approach in that regard. His work was choreographed—down to the millimeter—in its display. Conceptually, my overarching structure is consistent, but how it manifests is completely relative. It’s almost site-specific in that sense. I’m not married to a specific vision.

CW: It’s interesting how these shows relate specifically to the books. Almost as if the books were roadmaps.

ZC: The books are a critical component. They act as guides for both the viewer and for me. The intention of the whole project, books and installations included, is to interrupt our expectations of looking. At first she looks like a sexy blonde lady; once people look a little longer, that idea becomes stilted. In contrast to being about the story that surrounds the work (she was a friend of my aunt, she was a prostitute, anything else), the duBois project is about all of the elements that make up the gestalt. It resists narrative.

CW: Do people think it’s you?

ZC: All the time. I see it a lot on blogs. This is not a biopic! Even though it is from the archive of a real person, this is about fantasy. Both her fantasies and the fantasy of photography itself.

The Other Disappeared Nurse no.7 from The Vanishing of Michelle duBois, 2012

—

All images courtesy of the artist and Perry Rubenstein Gallery, Los Angeles. © Zoe Crosher

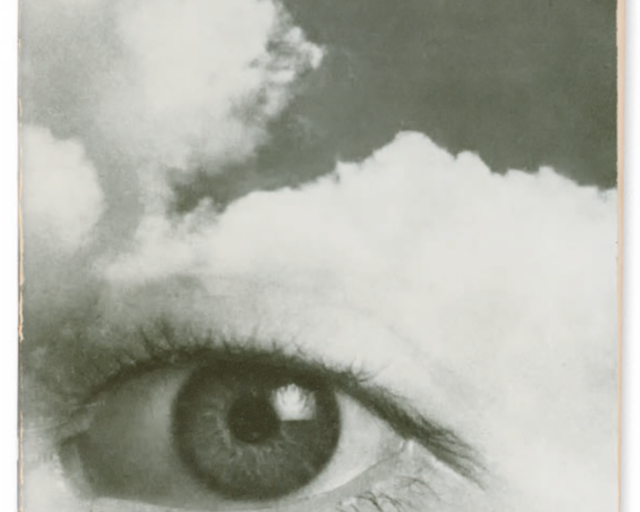

Mae Wested no.3 (Crumpled) from the series 21 Ways to Mae Wested, 2012

Digital C-Print

36 x 36 inches

Edition of 6 + 2 AP

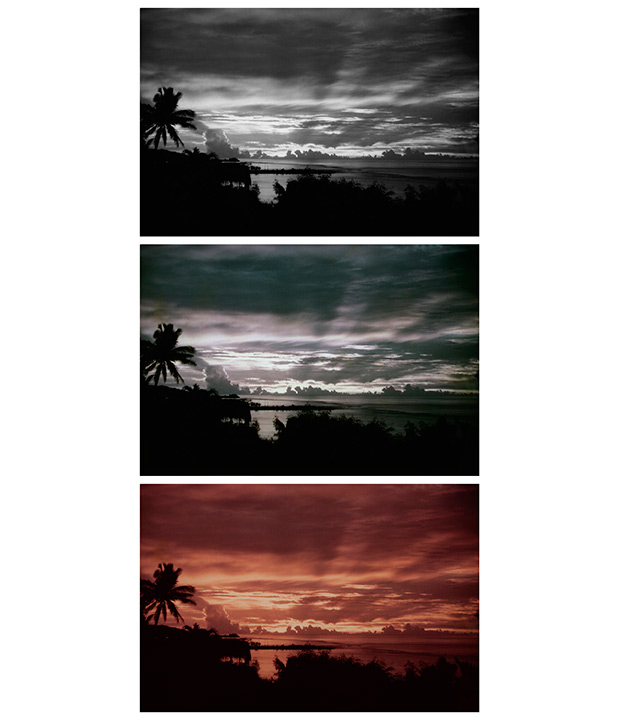

duBois’ Triple Vision Fantasy Landscapes (Sunset)

2012 Digital C-Print

84 7/8 x 41 7/8 inches

Edition of 6 + 2 AP

No.9 from The Additive Dust Series (GUAM 1979) from The Disappearance of Michelle duBois

2012 Archival pigment print

13 x 19 inches

Edition of 6 + 2 AP

Tilt of her Head, Over Analog Time (from the series the Disbanding of Michelle Dubois), 2001-2011, by Zoe Crosher

(Nine) Photography and Mixed Media

Modern and Contemporary Art Council, 2011 Art Here and Now Purchase

© Zoe Crosher/ZC International 2012

Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

The Other Disappeared Nurse no.7 from The Vanishing of Michelle duBois, 2012

Pigmented Ink on Museo Silver Rag

29 7/8 x 23 3/8 inches

Edition of 6 + 2 AP