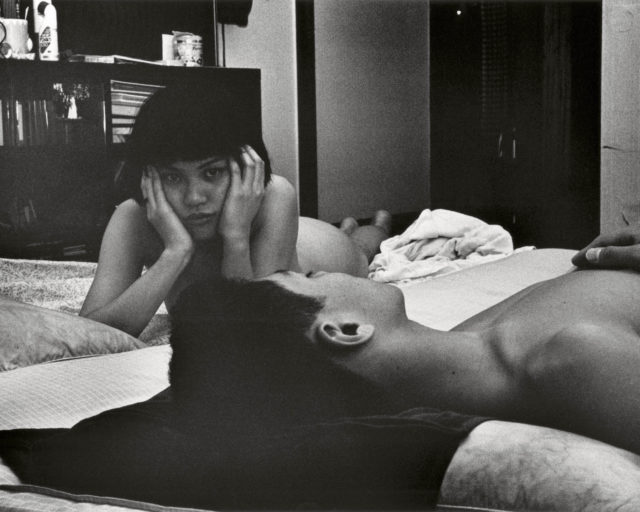

Jamal Nxedlana, FAKA Portraits, Johannesburg, 2019, for Aperture

“Can we give Fela the other socks, the glittery ones?” Jamal Nxedlana asks stylist and makeup artist Orli Meiri, a short, talkative brunette in bright yellow Y-3 Kaiwa sneakers. She agrees. It’s Sunday afternoon on the calmer side of Yeoville’s ground zero—Rockey Street, where the back seat of a black Toyota Yaris has been transformed into a changing room for Nxedlana’s collaborators this afternoon, FAKA.

Many an artist’s heart has been found, loved, lost, and broken in this infamous oasis of social intercourse, often unfairly considered the Sodom and Gomorrah of Johannesburg by apartheid’s Calvinistic legacies. Today, in the aftermath of the glow of some of its ascended rock-star ancestors—the era-defining singers Brenda Fassie and Lebo Mathosa, the globetrotting trumpeter Hugh Masekela—it has transformed into a neatly sliced pie of religious zealots; hardworking, working-class families from all over Africa; weed dens; struggling creatives; and cyber scammers. Our little scene is unfolding on the doorstep of Times Square, built on one of Yeoville’s many documented intergalactic spiritual portals. A bevy of heterosexual men are drinking and sweating and drinking, following Nxedlana’s motley crew with their eyes.

Pint-size and protean since 1985, Nxedlana wears an unassuming all-black ensemble and never puts down his camera. He has been diligently creating and archiving small borderless worlds since 2006, both independently and collaboratively with the Cuss Group artist collective—whose projects span various disciplines of cultural production, including audiovisual exhibitions, installations, and the publication of print and digital media—and with Bubblegum Club, the pulsating living-culture website he cofounded and oversees from his Braamfontein offices.

When Fela Gucci (Thato Ramaisa) and Desire Marea (Buyani Duma), who, in 2015, created the performance duo FAKA (a Nguni word meaning “insert it” or “put it in”), eventually emerge from the car in matching outfits from head to ankle—blue-and-pink punctured tube tops, glittery red caps, chunky silver hoop earrings, camouflage booty shorts, and turquoise khunkqu belts—they look like the underage, Black Label beer–drinking, older cousins of the kids in Brenda Fassie’s music video for her 1987 hit “Ag Shame Lovey,” otherwise known as “Midodo.” Nxedlana bought the outfits with FAKA the day before at Small Street Mall, Johannesburg’s working-class shopping haven, where cheap Chinese fashion goes to be resurrected in the limitless fountain of poor black youth.

Trailing the performative heels of visual artists like Athi-Patra Ruga and celebrities like the 2000s queer South African pop group 3Sum, FAKA are interdisciplinary artists in their own right, and the muses of muses both in South Africa and abroad, raking in nods from the likes of Solange, Donatella Versace, Moses Sumney, and myriad independent music festivals as the queer envoys of gqom, arguably the most influential musical genre in South Africa right now. This attention is owed to the artful confluence of how they appear, where they are, and what they say. Their curated looks often transcend gender, race, and class binaries using uncategorized clothing, makeup, and hairstyles. And perhaps not unlike the title character in Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando, they escape the confines of linearity as figures from the ongoing past, becoming somehow all genders, all ages, all times all at once.

Fela stands on the busy pavement looking at the blue sky with a cigarette in one hand and a Black Label quart in the other. An exquisite, waiting Desire sits on a white plastic stool, getting their extra eyebrows did. This person knows love. The way they sit—under a sun so hot it burns like it was hung by a short person—is with a gracious knowing hardly embodied by humans born in the 1990s, hardly deployed by those who are intimate with Internet fame, encapsulated in a tweet put out in July 2018 by Desire: “I am guilty of internalising a narrative that isn’t mine. I was actually very fortunate to have a supportive family who told me that I could be ANYTHING. My aunts and my grandmother invested in my greatness first. I’m learning to embrace that part of my story.”

All photographs courtesy the artist

To the observant eye, beneath the unsophisticated sheen of Johannesburg’s new-money basicness is a grime so glorious, so magnanimous, that to name it would be premature. And greedy. Inside this grime is some borrowed sugar from the future-past, the granules of which are a mix of Bantu, the Internet, post-wokeness, and spirit. You will not find FAKA anywhere near a march or a protest. They are a protest, an intervention, and a performance by virtue of being. In a taxi, a mall, or onstage. A perpetual traveling installation of sweet, sweet liberation.

Read more from Aperture issue 235, “Orlando,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.