The Brilliant Light of California’s Beaches

Tod Papageorge speaks about his photographs of skin, swimsuits, sand, and surfboards—and what it’s like bringing a medium-format camera to the beaches of Los Angeles.

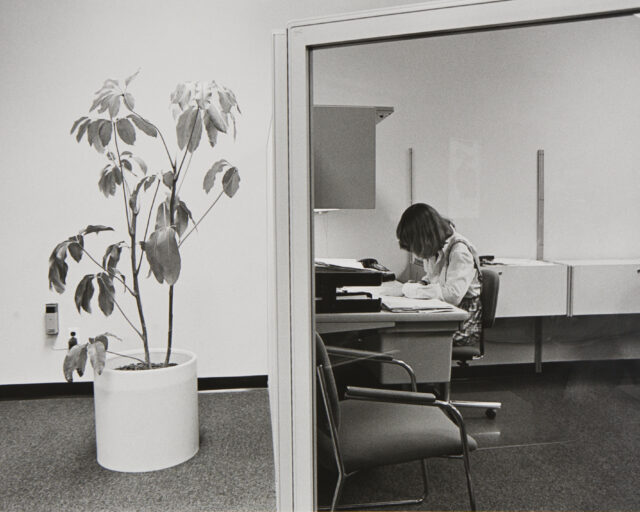

Tod Papageorge, At the Beach, 1975–80

In 1975, the thirty-five-year-old photographer Tod Papageorge took a cross-country trip that ended on the beaches of Los Angeles. There, challenged by the play of the brilliant light on skin, swimsuits, sand, water, and surfboards, he experimented with the descriptive qualities of the medium-format camera he brought with him. Employing a machine that produced a negative four times larger than his usual Leicas, Papageorge aimed to create poetry from the details of the physical world. Over the years, he returned to those beaches, and several others along the coast, three more times. Now, fifty years later, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Connecticut is presenting an exhibition of these images, previously shown on the West Coast at James Danziger Gallery and in Europe at Thomas Zander Galerie, and published as a book in 2023.

Papageorge began taking photographs during his final semester at the University of New Hampshire. In a basic technical class, he saw a few early pictures by Henri Cartier-Bresson, which struck him as the visual equivalent of the poetry he was studying and attempting to write. Observing how the French photographer created pictures à la sauvette changed the course of his life. Following graduation, and a year each in San Francisco and Boston, he set out for Europe and cities like Seville and Paris, where Cartier-Bresson also had made much of his early work. On his return to the states, in late 1965, Papageorge moved to New York, and soon became part of a group of photographers—including his boyhood friend Paul McDonough, as well as Joel Meyerowitz, and Garry Winogrand—that met regularly to photograph together, and, for one extraordinary period, convened in a weekly salon at Winogrand’s apartment, where they would look at work and discuss their shared passion.

Papageorge, a distinguished teacher, was himself schooled in the streets, sidewalks, parks, and nightclubs of Manhattan, and on his cross-country trips. His work has been collected in numerous monographs, including Passing Through Eden: Photographs of Central Park (2007); American Sports, 1970, or How We Spent the War in Vietnam (2007); Opera Città (2010); Core Curriculum: Writings on Photography (2011); Studio 54 (2014); Dr. Blankman’s New York: Kodachromes 1966–1967 (2017); On The Acropolis (2019); and At the Beach (2023). After curating Public Relations, the influential 1977 Garry Winogrand exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Papageorge embarked on a new chapter. He led the MFA program in Photography at the Yale School of Art from 1979 through 2013. Graduates during his tenure include Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Abelardo Morell, Dawoud Bey, Mark Steinmetz, An-My Le, Justine Kurland, Katy Grannan, Victoria Sambunaris, Richard Mosse, Kristine Potter, and the program’s current director, Gregory Crewdson. Ahead of the exhibition in Connecticut, I spoke with Papageorge about concentration, good vibrations, and why the hard work of photography is always a pleasure. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for space.

Lisa Kereszi: I read that you made the first round of beach pictures in Los Angeles at the tail-end of a road trip in 1975. What was the intention of driving cross-country?

Tod Papageorge: To photograph.

Kereszi: In the tradition of Robert Frank’s The Americans and Walker Evans’s American Photographs?

Papageorge: Every serious photographer was still thinking about The Americans in 1975, twenty years after the pictures were made, at least every photographer with a heart or brain. I was also thinking a lot about Garry Winogrand’s cross-country trip in 1964, which I consider one of the miracles of twentieth-century American photography, equally important in its own way as The Americans, in how it extended Frank’s discoveries.

Kereszi: How long would you stay in LA? A couple of weeks, a month, a couple of months each time?

Papageorge: Not months—a week or two at a time.

Kereszi: Did you come back from each trip with twenty rolls, fifty rolls?

Papageorge: We’re talking about less than one hundred and fifty rolls of 120 film over the four trips I eventually made to the beaches, eight exposures a roll. I’d started using medium-format cameras in 1973, which, because they produced negatives four times larger than my usual Leicas, beautifully described the brilliant light and casual lifestyle I found in California. Those six-neuf cameras (6-by-9 cm) also had the same 2-by-3 shape as the Leica, one that, by 1975, after thirteen years of practice, was hard-stamped on my picture-making brain-apparatus machine. So, because I generally knew what the edges of the frame were going to be when I was ready to take a picture, the act itself was simply a case of lifting the machine in a single gesture and pressing the shutter, tout de suite. Because the shutter speed was relatively slow at 125th of a second, this process was necessarily somewhat deliberate, but, again, consisted of a single action, usually for a single exposure, up and done. By that point in my evolution as a photographer, I was pretty good at recognizing the moment when my subject, or subject field, was cohering enough that I had a good chance of capturing at least a clear picture, if not a strong one . . . a long way of explaining that I didn’t shoot a lot of film.

Kereszi: On the nude beach, did people have a problem with you photographing?

Papageorge: No. I was discreet and quick.

Kereszi: But you had that big camera.

Papageorge: I’d wait and wait. When I talk about the picture being clarified, that’s exactly what I mean, the form being clear, or coalescing into clarity, across the frame. Which, of course, is what I was waiting for. And I’m not talking about simple pictures. On the contrary, they’re generally complex, where the challenge to making them was to really concentrate until I saw, or sensed—since, before anything else, this is a physical process—that the action in front of me was gathering into a readable form.

Kereszi: I am still trying to picture the entire scene with you in it.

Papageorge: I was dressed normally on both the regular beach and the nude beach. I wasn’t walking around in a bathing suit.

Kereszi: I’m imagining you’re standing there composing.

Papageorge: But I’m not composing. I’m watching intently, more animal than citizen. The camera’s not at my eye. I’m never looking through the camera.

Kereszi: Did you feel separate from what was going on, like there was a stage?

Papageorge: Good question. A stage. Particularly when I was using those 6-by-9 cameras: a stage, almost literally so.

Kereszi: There’s a physical distance?

Papageorge: Yes. With that machine, you need a certain physical distance to get the necessary depth of field and definition.

Kereszi: You say you felt separate, but did you interact with the people on the beach? Like, did you have a towel that you sat on? Or were you always walking?

Papageorge: I had no friends with me. And I never said a word to anyone there.

Kereszi: Are there pictures of people making eye contact that have been edited out?

Papageorge: Why? Did you notice that there were people making eye contact?

Kereszi: They’re not. It’s incredible. Which makes me wonder if the beach project was somehow an experiment for you?

Papageorge: In a way, yes, as in, Can this really be done? Or, Is it possible to use a clunky camera to contain and form coherent, meaningful pictures out of this complicated, shifting energy field of bodies? It’s always an experiment, but yes, the beach presented its own special problem.

Kereszi: When I asked you if there were any poems or a piece of writing that I could reference or think about in relation to these pictures, you mentioned the chorus to the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.”

Papageorge: Yes, but I didn’t know from the Beach Boys back then, or even today. I just felt a vibration when you asked the question.

Kereszi: But in retrospect, were you serious in mentioning it, was there some meaning to it?

Papageorge: Well, in a short text that I wrote in 1988 about these pictures, I suggested that the typical red-blooded American male carried around some mental image of the surfer and the California beach girl. So, I guess to that degree, I was serious. But I can’t really say I knew what I was talking about, beyond making an obvious reference to a cultural image created a few miles away from those beaches, in Hollywood. I’d never even seen an Annette Funicello movie—Beach Bikini, or whatever it was called, or any of the others.

Kereszi: Beach Blanket Bingo. I dug into the lyrics a little bit and tried to think about what you might be suggesting in mentioning it. There was a lot written at that time around the idea of psychedelia and “tuning in,” that “vibrations” had something to do with the ’60s idea that everybody was connecting to something and with one another, connecting with a vibe. But that has nothing to do with anything you’re saying, it seems.

Papageorge: It certainly has nothing to do with anything that I was working at. As you know, photography, at least out in the world of the “social landscape,” requires tremendous concentration and a virtually inflexible dedication to the job at hand, which, again, is to look intently. So, yes, good vibrations are fine for the people I might be photographing on the beach; in fact, the more they’re feeling them, the better it is for me because they’re acting within their own zone. But my zone is a different one—a zone of attention, you might say.

Kereszi: In your essay on Robert Adams, published in Core Curriculum, you discuss writing poetry, which you’d done as a college student, versus making photographs, and how the raw materials used in each medium might be related.

Papageorge: Both poetry and photography deal in the world, the world of things. To quote W. H. Auden: “It is both the glory and the shame of poetry that its medium is not its private property, that a poet cannot invent his words and that words are products, not of Nature, but of a human society which uses them for a thousand different purposes.” It’s an observation that also applies to the photographer and his or her dependence on the “ten thousand facts” of the physical world and, of course, Auden’s “human society.” To say it gracelessly, the job for the poet is to arrange the myriad “word-products” of language into poems that own the resonance of world-reflecting meanings as well as, one would hope, the music of sound, just as it is for the photographer to set his or her subjective curation of the world into a visible order that might be described as the music of things caught in a satisfying visual resolution.

Which reminds me to mention my love of music, something as important to my formation as an artist as anything else, including poetry or, once I’d started, making photographs. As it happened, by my junior year of college I knew, in a half-conscious way, that I was good at music, good at writing, and, later, good at photography. I eventually decided on photography (since it seems that I was destined to follow some kind of artistic trail) because I’d never been interested in being an orchestral musician and found poetry devastatingly difficult to deal with, given that my standard for it was very, very high. So photography came to supplant everything else. Not because it was easier, or because my eventual ambitions for it were any lower than my ambitions for poetry had been, but because it gave relatively quick and specific results, one frame after the next, where the elemental, binary vote of “good picture or bad picture” could be cast almost reflexively, with finality. No frustratingly incomplete poems to keep track of, or wither in the face of.

Kereszi: When you were a child, was there music in the house, or poetry?

Papageorge: Yes, there was music. My mother cared nothing for conventional homemaking; for example, I had to iron my own shirt for school every morning once I was tall enough to stand at the board. But there was an upright piano in the house, and every day she would sit at it and play. She’d taught herself, had perfect pitch, and every day she’d sit there to play and sing the popular American songbook. I’m sure that had a big effect on me.

Kereszi: You talk about symbols a lot in your essay on Evans and on Frank and in an interview with John Pilson. Are there symbols in the beach work?

Papageorge: No. There are bodies.

Kereszi: Bodies. Well, I also think about politics when I think about Frank’s work and symbols. And you started to make these beach pictures four years after American Sports, 1970, or How We Spent the War in Vietnam, right? I read in the same interview that you described yourself as being in a rage over Kent State while making the American Sports work. With this beach work being made just four years later, are you totally switching gears here—is there any political content?

Papageorge: There’s no political content, which isn’t to say that I wasn’t outraged by the political scene, certainly through the conduct of the Vietnam War and then later with Reagan. He was maddening to me. As were the two Bushes, totally maddening. Not that I was ever active politically. I never joined a group or marched or anything like that. So, no, the beach pictures are not political.

Kereszi: Well, it’s hedonism that you’re depicting; you’re showing hedonism, you’re showing escapism, recreation, while all this other stuff just goes on. Isn’t that part of your point? That subtitle of the sports book, How We Spent the War in Vietnam, makes it feel like you’re making a value judgment about all the mass distraction.

Papageorge: Yes, in that particular book. But when you consider my work in Central Park, Studio 54, the Acropolis, and, here, the beaches, you’ll see that these subjects share what might be called bounded realms or landscapes not unrelated to those we know from classical painting, poetry, music, and opera. In other words, there’s a more purely aesthetic ambition being explored in the work. I’m not saying it’s exalted: it’s not a Bach mass. But it is its own category, an aesthetic as distinct from the Leica pictures that make up my sports book as the Acropolis is distinct from Yankee Stadium.

Kereszi: On the escapism theme, though—when I think about these places that you’ve mentioned, like the island of Studio 54, the island of Central Park, the island of the beach, where people are getting away and escaping: you’re on the sidelines just watching?

Papageorge: No. And I don’t see those places as escapist at all. Rather they’re gifts, vivid and bright in themselves, but also grist for being transformed into poetry—as photographs! As crazy as Studio 54 is, as hot and exhausting as the Acropolis might be, as vibratory as Malibu seems, they’re all prelude to the possibility of becoming still pictures charged with meaning. My problem, then, far from simply watching, is to try to make pictures that express the feelings I’m imaginatively projecting from my experiences of life and art onto these arenas and ever shifting groups of people. To trace this process in any artist is complicated, if not impossible, as it’s necessarily tied up with the psycho-physio-cultural makeup of the person propelling it. It might be enough, though, to say, with Goethe, that “One only sees what one looks for. One only looks for what one knows,” which, in my case, has been the stew of poetry, art, and music—mixed with the meat and bones of a lucky life—that has effectively shaped me.

Kereszi: So these places and gatherings are occasions?

Papageorge: Yes, a good word.

Kereszi: Like occasions for compositions—for art?

Papageorge: Yes. In these cases, encouraged by the surrounding “realm.”

Kereszi: Right, they’re in that realm. But again, you’re not?

Papageorge: No. I’m totally in mine, while watching intently for what I’ve described as a kind of visual/musical gathering toward a picture—and, with that, perhaps, meaning. It’s not as if you’re making compositions, though; it’s more that you’re employing a unique system of visual indication—photographic description—to describe a discrete part of the world in a transparent way.

Kereszi: Speaking of that kind of visual clarity, in your essay on Robert Adams in Core Curriculum, you referred to the sun in his pictures as “pitiless.” And I would say some of that same light is in Walker Evans’s pictures: pitiless. Is it pitiless in your beach pictures?

Papageorge: No, no. On the contrary. It’s Titian blue, ultramarine (perfect word). Bouncing off the sand, picking up reflections and color. It’s glorious. Glorious light. And I think the photographs suggest that.

Kereszi: How did you know when this body of work was finished?

Papageorge: It’s all in the course of a life being lived and photographs being made. It’s not as if I’m just thinking about photographing with a big camera on a beach in Los Angeles through that period. I was also working in New York and, in the ’80s, making a lot of trips to Europe, to Paris, back and forth, photographing intensely, often with my Leicas.

Courtesy the artist and Stanley/Barker

Kereszi: So did you not feel pulled back to LA to photograph on a fifth trip?

Papageorge: At some point years after the fact of the four trips and making these pictures, I noticed on one of my contact sheets a few frames of Wilt Chamberlain sprawled in the sand. And I asked myself, Well, what are you going to do with these? There was also the more extensive beach work I’d done in 1988, on a grant from AT&T, sitting in a box. Not to mention that my wife, Deborah, a ballet dancer, always loved the pictures she’d seen from this body of work and encouraged me to push ahead with it. Leading me, finally, to collect the contact sheets, edit them, scan the selects, and discover that the whole thing added up to something worth exhibiting.

Kereszi: Earlier we were talking about this being something of an experiment. Can you define what you think you were looking for versus what you found?

Papageorge: Imagine first seeing it, the beach, the California beach, the California beach in glorious light: that’s the given. Which is a lot. But I don’t receive that gift expecting anything in particular from it. I have no image of that. I just know enough to realize it will be a process filled with delight. Because no matter how hard the work is, it’s a pleasure. It’s the pleasure of my life to make photographs.

Tod Papageorge: At the Beach is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Connecticut, Westport, June 26–October 26, 2025, along with In the Pool, a group show of selected graduate student work from the years Papageorge headed the photography program at the Yale School of Art.